Click to enlarge:

Select an image:

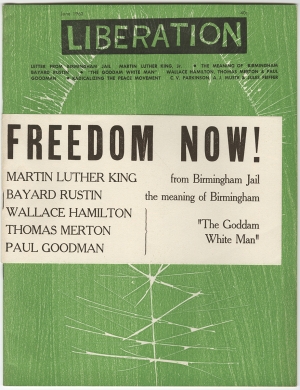

This issue of Liberation magazine includes the full text of Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” written on April 16, 1963, when King was jailed for disobeying a judge’s blanket injunction against “parading, demonstrating, boycotting, trespassing and picketing.” King and other civil rights protestors were arrested on April 12.

A supporter smuggled a copy of an April 12 newspaper to him, which included an open letter entitled “A Call for Unity.” Written by eight white Birmingham clergymen, representing Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish congregations, the letter opposed events “directed and led in part by outsiders” and urged local African Americans to negotiate and use the courts if they were denied their rights, rather than protest. These clergymen agreed that social injustices existed but insisted that the battle against racial segregation should take place in the courts and not in the streets.

Provoked by the letter from fellow clergymen, King began to write a response in the margins of the newspaper itself. He continued the letter on scraps of paper supplied by a supportive African American fellow inmate who served as a trustee and finished the nearly 6,000-word letter on a pad provided by his attorneys. Walter Reuther, the president of the United Auto Workers, arranged to pay $160,000 to bail out King and other jailed protestors.

MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR.

“Letter from Birmingham Jail,” in

Liberation: An Independent Monthly, June 1963, New York. 32 pp.

Inventory #27490.01

Price: $3,500

Excerpts

“While confined here in the Birmingham City Jail, I came across your recent statement calling our present activities ‘unwise and untimely.’ Seldom, if ever, do I pause to answer criticism of my work and ideas.... But since I feel that you are men of genuine goodwill and your criticisms are sincerely set forth, I would like to answer your statement in what I hope will be patient and reasonable terms.” (p10/c1)

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly affects all indirectly.” (p10/c2)

“Birmingham is probably the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States. Its ugly record of police brutality is known in every section of this country. Its unjust treatment of Negroes in the courts is a notorious reality. There have been more unsolved bombings of Negro homes and churches in Birmingham than in any other city in this nation. These are the hard, brutal, and unbelievable facts.” (p11/c1)

“So, the purpose of direct action is to create a situation so crisis-packed that it will inevitably open the door to negotiation. We, therefore, concur with you in your call for negotiation. Too long has our beloved Southland been bogged down in the tragic attempt to live in monologue rather than dialogue.” (p11/c2)

“My friends, I must say to you that we have not made a single gain in civil rights without determined legal and nonviolent pressure. History is the long and tragic story of the fact that privileged groups seldom give up their privileges voluntarily.” (p11/c2)

“We must come to see with the distinguished jurist of yesterday that ‘justice too long delayed is justice denied.’ We have waited for more than three hundred and forty years for our constitutional and God-given rights.” (p12/c1)

“I guess it is easy for those who have never felt the stinging darts of segregation to say ‘Wait.’ But when you have seen vicious mobs lynch your mothers and fathers at will and drown your sisters and brothers at whim; when you have seen hate filled policemen curse, kick, brutalize, and even kill your black brothers and sisters with impunity; when you see the vast majority of your twenty million Negro brothers smothering in an airtight cage of poverty in the midst of an affluent society; when you suddenly find your tongue twisted and your speech stammering as you seek to explain to your six-year old daughter why she can’t go to the public amusement park that has just been advertised on television, and see tears welling up in her little eyes when she is told that Funtown is closed to colored children, and see the depressing clouds of inferiority begin to form in her little mental sky, and see her begin to distort her little personality by unconsciously developing a bitterness toward white people; when you have to concoct an answer for a five-year old son asking in agonizing pathos: ‘Daddy, why do white people treat colored people so mean?’; when you take a cross country drive and find it necessary to sleep night after night in the uncomfortable corners of your automobile because no motel will accept you; when you are humiliated day in and day out by nagging signs reading ‘white’ and ‘colored’; when your first name becomes ‘nigger’ and your middle name becomes ‘boy’ (however old you are) and your last name becomes ‘John,’ and when your wife and mother are never given the respected title ‘Mrs.’; when you are harried by day and haunted at night by the fact that you are a Negro, living constantly at tip-toe stance never quite knowing what to expect next, and plagued with inner fears and outer resentments; when you are forever fighting a degenerating sense of ‘nobodiness;’ then you will understand why we find it difficult to wait.” (p12/c1)

“there are two types of laws: there are just laws, and there are unjust laws. I would agree with St. Augustine that ‘An unjust law is no law at all.’... A just law is a man-made code that squares with the moral law, or the law of God. An unjust law is a code that is out of harmony with the moral law.” (p12/c2)

“I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate.... Shallow understanding from people of goodwill is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will.... We will have to repent in this generation not merely for the vitriolic words and actions of the bad people, but for the appalling silence of the good people.” (p13/c1-2)

Historical Background

As president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Martin Luther King Jr. traveled from his home in Atlanta, Georgia, to Birmingham, Alabama, which he labeled as “probably the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States.” He went to support Fred Shuttlesworth, the pastor of a Baptist church and the organizer of the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights. King worked with local leaders to create and implement “Project C,” the “C” standing for confrontation, in early 1963. The Birmingham campaign began on April 3, 1963, with a program of nonviolent direct action that included sit-ins, business boycotts, and marches that were intended to provoke mass arrests.

On April 10, Birmingham’s Commissioner of Public Safety, Eugene “Bull” Connor, obtained an injunction against the protests and raised the cost of bail bonds. On April 12, King and fifty Birmingham residents aged from 15 to 81 were arrested and sent to jail for violating the injunction. The arrest of King sparked protests at national retail chains with stores in downtown Birmingham, and business owners pressed the administration of President John F. Kennedy to intervene. King was released on April 20, after Walter Reuther of the United Auto Workers arranged the payment of bail.

Barbara Deming, one of the few white people arrested in the Birmingham demonstrations, was an associate editor for Liberation

When the campaign ran out of adult volunteers, organizer James Bevel trained college, high school, and even elementary students in nonviolence. When they walked from downtown churches toward City Hall in groups of fifty on May 2, more than six hundred students were arrested.

With jails full beyond capacity, at the direction of Connor, the Birmingham Police Department used attack dogs and high-pressure water hoses on adults and children alike to keep them out of the downtown area. By mid-May, after bombings of black businesses and homes and retaliatory violence against white businesses, the Kennedy administration deployed three thousand federal troops to Birmingham to restore order, over the objections of Alabama’s segregationist governor George Wallace.

Media coverage drew the nation’s and the world’s attention to racial segregation in the South. The campaign elevated King’s reputation as a civil rights activist, turned Connor out of his job, and forced desegregation in Birmingham. Later that year, King gave his “I Have a Dream” speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, Time named King its Man of the Year for 1963, and he won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964.

Publication History

Harvey Shapiro, an editor for The New York Times Magazine, asked King to write his letter for publication in the magazine, but the Times chose not to publish it. The New York Post Sunday Magazine of May 19, 1963, published extensive excerpts from the letter, without King’s consent.

The complete letter was first published in May 1963 as a 16-page pamphlet entitled Letter from Birmingham City Jail by the American Friends Service Committee, a Quaker organization formed in Philadelphia during World War I to aid conscientious objectors.

The first national periodical publication was in the June 1963 issue of Liberation, followed by The Christian Century (June 12), and The New Leader (June 24). The letter continued to grow in popularity throughout the summer and appeared in The Progressive (July 1963) under the headline “Tears of Love”; The Atlantic Monthly (August 1963) under the headline “The Negro Is Your Brother”; and in Ebony (August 1963) with the title “A Letter from Birmingham Jail.” King revised the letter and included it in his 1964 memoir of the Birmingham campaign, Why We Can’t Wait.

Additional Content

This issue also includes articles entitled “The Meaning of Birmingham” by civil rights activist and co-editor of Liberation Bayard Rustin; “‘The Goddam White Man’: Let’s Along and Do the Murder First” by novelist Wallace Hamilton; “Neither Caliban nor Uncle Tom” by American Trappist monk Thomas Merton; and “The Only Grounds for Solidarity” by social critic Paul Goodman; “Levelling with the Public” by C. V. Parkinson; and “Let’s Radicalize the Peace Movement” by Dutch-born clergyman and pacifist A. J. Muste, also a co-editor of Liberation. It also includes a poem entitled “The Destruction” by Ronald Breiger and an editorial cartoon, “The Peace Image,” by cartoonist Jules Feiffer.

Liberation (1956-1977) was a bimonthly and then monthly pacifist magazine published in New York City. Founded, edited, and published by David Dellinger, Bayard Rustin, Sidney Lens, Roy Finch, A. J. Muste, and Glen Gardner, the magazine identified with the New Left political movement and campaigned for civil and political rights, environmentalism, gay rights, and reforms in gender roles and drug policies. It supported the Cuban Revolution and opposed the Vietnam War. Children’s book author Vera Williams prepared the artwork for many of the covers. Its June 1963 issue contained the first full publication of Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail” and the first version with that title.