Click to enlarge:

Select an image:

DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE.

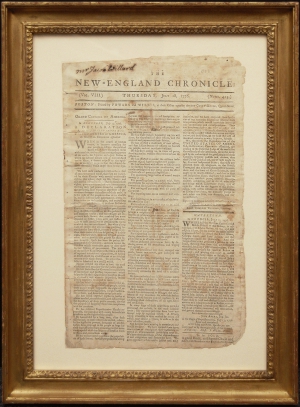

The New-England Chronicle, July 18, 1776, Vol. VIII No. 413. Newspaper, with the entire text of the Declaration on page 1 of 4. Subscriber’s name “Mr Jacob Willard” written at top of page 1. Boston: Printed by Powars & Willis.

Inventory #21074

SOLD — please inquire about other items

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal…”

A rare and displayable July 1776 printing of the Declaration of Independence that gave many Bostonians their first view of America’s immortal founding document – even before it became ‘unanimous’[1]. Only ten copies of New-England Chronicle issue are known, eight of which are held by institutions. This is one of just two on the market in the past 40 years.

Printing and Distributing the Declaration

Printed copies of the Declaration were sent from Philadelphia by John Hancock and others, starting on July 5th. The Declaration was circulated as thoroughly and as quickly as possible that Revolutionary summer. Timeliness of publication depended on how long the initial copies spent in transit, as well as the newspapers’ printing schedules, in most cases once a week.

|

Own a Piece of History. To see our current inventory of copies of the Declaration of Independence and Declaration signers related material click here.

|

The earliest copies arrived in Boston on Saturday, July 13th, according to Dr. Samuel Cooper, patriot pastor of Brattle-Street Church. Town officials held a public reading from the state house balcony on July 18th. This issue of The New-England Chronicle was published the same day, along with John Gill’s simultaneous publication in the city’s Continental Journal. No other Boston printing is known to have preceded them. (The one identified Boston broadside was produced by Powars and Willis, in partnership with Gill; it probably followed the newspaper printings.)

The first Massachusetts printing was a broadside issued in Salem ca. July 13th-15th, and then in the July 16, 1776 issue of Ezekiel Russell’s American Gazette. On July 17th, the Massachusetts council ordered an official broadside printing to be sent to all parish ministers for public reading, and then to be recorded by town clerks in the town’s books.

By the end of August 1776, the Declaration had been printed in at least 29 newspapers and 14 broadsides; all are extremely rare on the market. The last copy on the market of the first official broadside (one page) of the Declaration, by John Dunlap, sold at Sotheby’s in June 2000 for $8,140,000, but has subsequently been re-sold privately for significantly more. The last copy on the market of the first newspaper printing, the July 6, 1776 Pennsylvania Evening Post, sold at Christie’s in 2007 for $360,000. The last Salem official broadside on the market, in 2004, sold for $456,000. And the last copy on the market of the Boston broadside, printed by Gill and Powers, sold at Christie’s on June 24, 2009, for $693,500.

The New-England Chronicle easily beat out the official state printing. That broadside, prepared in Salem by Ezekiel Russell, was not distributed until later July or early August. Abigail Adams heard it read in her Boston church on August 11 – three weeks after Powars and Willis published their scoop.

Other content in this newspaper

The pages of this issue provide context from that critical month. Articles detail:

· The “acclamations of joy” following the reading of the Declaration to Continental troops in New York, and the news that “The Congress for ‘the State of New-York have resolved unanimously, that they will, at the risque of their lives and fortunes, join with the other Colonies in supporting the Declaration.’”

· The arrival of Connecticut reinforcements in New York City (“as fine a body of men as any engaged in the present grand struggle for Liberty and Independence”).

· A report from Trenton that up to 10,000 British troops had landed on Staten Island.

· A famous act of patriotic vandalism in today’s Wall Street area (“Last Monday evening the statue of King George the Third, on horseback, in the Bowling-green was taken down, broken to pieces, and its honor levelled with the dust”). It was then melted down and cast into musket balls.

· Fears of biological warfare by the British “barbarians.” “A. B.”writes: “The Small-Pox has ever been a most formidable foe to New-England and its armies. Our enemies knowing this, have taken inhuman pains to propagate it among us; for no barbarians could exceed them in the methods they have employed to distress and destroy us. In this, Heaven has permitted them to succeed, but at the same time has given us in innoculation an astonishing means of robbing this disease of its terror and fatality. At this critical season, we cannot be too speedy or diligent in every where applying this inestimable gift of Heaven for our own security.” (p. 3, col. 2)

· A letter from Lieut. Col. Archibald Campbell of the 71st Regiment of Highlanders to General Howe provides an eyewitness account of the capture of his battalion by an American fleet of privateers in Boston Harbor. He apologizes for having “fallen into the hands of the Americans. . . Since our captivity I have the honor to acquaint you, that we have experienced the utmost civility and good treatment from the people of power at Boston, insomuch, Sir, that I should do injustice to the feelings of generosity, did I not make this particular information with pleasure and satisfaction….” [2] (p. 2, cols. 1-2)

· On the last page, notices from Samuel Langdon, president of Harvard College, announce the cancellation of public commencement ceremonies “in Consideration of the difficult and unsettled State of our public Affairs” and set a date for examinations of prospective students.

Historical Background

In the wake of the Battles of Lexington and Concord, followed by King George’s proclamation that the colonies were “engaged in open and avowed rebellion,” the Continental Congress decided enough was enough. The committee appointed to draft a statement declaring independence turned the task over to their most eloquent writer, Thomas Jefferson. In Philadelphia on July 4, 1776, after some revision, Congress formally adopted his declaration. Church bells rang in Philadelphia, and word was spread throughout the colonies. Thus a new nation was born.

On July 18th, the same day that The New-England Chronicle published it, the Declaration was proclaimed by Col. Thomas Crafts from the balcony of the State House in Boston. Abigail Adams wrote to John Adams that

“…great attention was given to every word. As soon as he ended, the cry from the Belcona, was God Save our American States and then 3 cheers which rended the air, the Bells rang, the privateers fired, the forts and Batteries, the cannon were discharged, the platoons followed and every face appeard joyfull. Mr. Bowdoin then gave a Sentiment, Stability and perpetuity to American independance. After dinner the kings arms were taken down from the State House and every vestage of him from every place in which it appeard and burnt in King Street. Thus ends royall Authority in this State, and all the people shall say Amen.”[3]

Multiple thirteen-gun salutes honored the Union of thirteen colonies. Boston had only recently driven occupying British troops from the city after a prolonged confrontation lasting from July 1775 to March 1776. The siege of Boston ended when American troops fortified Dorchester Heights overnight with artillery trained on British ships in the harbor. The fleet sailed away in defeat and General Howe turned his efforts to capturing New York. Washington anticipated this strategy and strengthened his forces in New York in preparation for its defense.

This newspaper also addresses fears of biological warfare. The British had long been suspected of using smallpox as a weapon. During the French and Indian War (1754-1767), the commander of British forces in North America had proposed infecting hostile Indian tribes. (Because smallpox was rampant in Britain, most of the troops had gained immunity.) One article in this issue claims that the British had now attempted to infect Continental troops, by leaving blankets behind when they evacuated Fort Johnston in North Carolina.

For the Americans, inoculation was an option with considerable drawbacks. The procedure used a live virus, causing a mild form of the disease that could spread contagion. Washington, himself a smallpox survivor, was reluctant to endorse inoculation because his troops would be incapacitated during recovery; Benedict Arnold issued an order in February 1776 forbidding it. Since the army was already infected, new recruits quickly fell victim to the disease. During the 1775 siege of Quebec, up to a third of the American troops were ill with smallpox, signaling that the disease itself could affect the course of the war. By the winter of 1777 at Valley Forge, General Washington had reversed his policy. That decision was pivotal in winning the war in the South, providing an army of fighting men who were immune to the scourge of smallpox.

Bostonians were particularly fearful of smallpox. In 1721, an epidemic had infected half of Boston’s 12,000 citizens. This newspaper prints the texts of two recent acts, one to restrict travel in and out of the city by recently inoculated persons or those who still had active cases of the disease, and the other to provide for the establishment of hospitals where inoculations could be supervised and inoculees quarantined. Violators would be subject to stiff fines, whipping, or imprisonment. The acts were passed in the hope that they “may tend greatly to the preservation of the lives of the good people of this Colony.”

References

Brigham, Clarence S. History and Bibliography of American Newspapers. Worcester,

MA: American Antiquarian Society, 1947.

Diamond, Jared. Guns, Germs, and Steel. New York: W. W. Norton, 2005.

Franke-Ruta, Garance. “George Washington’s Bioterrorism Strategy: How We Handled It

Last Time,” Washington Monthly (Dec. 2001)

Hazelton, John H. Declaration of Independence, Its History. NY: Dodd, Mead, 1906.

Massachusetts Historical Society, Adams Family Papers, Letter from Abigail Adams to

James Adams, 21-22 July 1776, found at www.masshist.org/DIGITALADAMS/AEA/cfm/doc.cfm?id=L17760721aa.

Reidel, Stefan, M.D., Ph.D. “Edward Jenner and the History of Smallpox and

Vaccination.” Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings (Jan. 2005) 18(1):21-25.

Shields, Robin. “Publishing the Declaration of Independence,” found at

www.loc.gov/rr/program/journey/declaration.html.

Walsh, Michael J. “Contemporary Broadside Editions of the Declaration of

Independence.” Harvard Library Bulletin 3 (1949).

[1] The Declaration became unanimous on July 9, 1776 when New York finally voted in favor. The title of the Declaration was changed to “The Unanimous Declaration . . .” in August 1776, when the signed vellum copy was engrossed.

[2] Campbell adds a request to General Howe to negotiate a release for his men and himself, if possible. That release was consequential, as it turned out: Campbell went on to lead the 3,500 British troops that captured the city of Savannah, Georgia in December 1778.

[3] Abigail Adams to John Adams, July 21-22, 1776.