Click to enlarge:

Select an image:

“a discussion upon a section of a Malitia bill freeing the wife & children of the slave that enlist will occupy most if not all the day.”

[AFRICAN AMERICAN SOLDIERS].

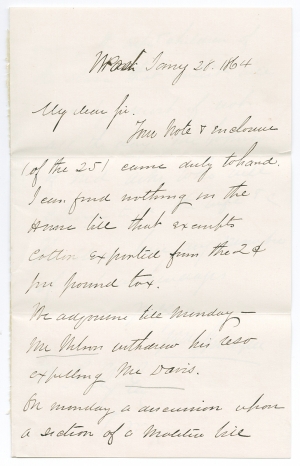

William Sprague, Autograph Letter Signed, to William D. Ely, January 28, 1864, Washington, D.C. 2 pp., 5 x 8 in.

Inventory #26531

Price: $1,250

Complete Transcript

Wash Jany 28, 1864

My dear sir.

Your note & enclosure (of the 25) came duly to hand. I can find nothing in the House bill that exempts cotton exported from the 2¢ per pound tax.

We adjourn till Monday. Mr. Wilson withdrew his reso expelling Mr. Davis.

On Monday a discussion upon a section of a Malitia bill <2> freeing the wife & children of the slave that enlist will occupy most if not all the day. Mr. Johnson of Md asks who will claim to be the wife &c. The slaves have any number of such appendages.

Res Yours

Wm Sprague

Wm D Ely Esq / Prov RI

Historical Background

On January 12, 1864, Congressman Thaddeus Stevens (1792-1868) of Pennsylvania, from the Committee of Ways and Means in the House of Representatives, introduced House bill H.R. 122 to increase the internal revenue. On March 7, 1864, President Abraham Lincoln signed the bill into law. In addition to duties on liquor, the act imposed a duty of two cents per pound on all cotton “produced or sold and removed for consumption” except for all cotton sold by or on account of the government of the United States. When cotton from the rebel states arrived at any port, assessors there were to assess the taxes due and report that information to the collector for receiving payment from the owner. As a textile mill owner as well as a lawyer, Ely likely hoped to avoid paying the tax on cotton that was exported to Europe. The act did provide for a drawback of two cents per pound on the three per centum duty on articles when they were exported that were exclusively manufactured of cotton on which the tax had been paid.

On July 17, 1862, Congress passed the Militia Act of 1862 to enable President Lincoln to enlist African-American soldiers. States that could not meet the quota for volunteers were authorized to conduct a militia draft and were allowed to enlist African Americans as soldiers and laborers. Section 13 of the Act stated that “when any man or boy of African descent who by the laws of any State shall owe service or labor to any person who, during the present rebellion, has levied war or has borne arms against the United States, or adhered to their enemies by giving them aid and comfort, shall render any such service as is provided for in this act, he, his mother and his wife and children, shall forever thereafter be free....” Thus, the act limited the offer of emancipation to slaves whose masters were in rebellion against the United States and did not apply to the slaves of loyal masters.

On January 8, 1864, Senator Henry Wilson (1812-1875) of Massachusetts introduced Senate Bill 41 “to promote enlistments in the army of the United States, and for other purposes.” The second section provided that African American soldiers and sailors would receive the same uniforms, arms, and pay as other soldiers. The third section offered freedom to any enslaved African American who joined the army or navy and to his mother, wife, and children without mention of the loyalty of their masters.

On January 27, Senator John B. Henderson (1826-1913) of Missouri proposed an amendment to the third section of the bill to strike out the words “his mother, and his wife and children” after “he” in section three of the bill so that it would read, “That when any person of African descent, whose service of labor is claimed in any State under the laws thereof, shall be mustered into the military or naval service of the United States he shall forever thereafter be free, &c.” The amendment also provided that the mother, wife, and children of any such soldier would also be free if they were owned by any person who had “given aid or comfort to the existing rebellion against the Government” since July 17, 1862, the date of the Militia Act of 1862.

Before voting on the amendment, Senator Reverdy Johnson (1796-1876) of Maryland made an extensive statement in support of the amendment. Johnson began by stating that “I doubt very much if any member of the Senate is more anxious to have the country composed entirely of free men and free women than I am.” However, he insisted that “From the beginning of the Government up to the present time...it has been the conceded doctrine that slavery within the States was an institution depending entirely upon the constitution and laws of the State, with which the Government of the United States had no authority at all to interfere.” Speaking of President Lincoln, he continued, “in his original proclamation that was followed up eventually by the proclamation emancipating the slaves, he expressly confined the operation of that proclamation to slaves within the States where there existed a rebellion against the authority of the United States. He excepted all Maryland; he excepted Kentucky; he excepted portions of Virginia; he excepted portions of Louisiana; and, as I understood, he thought that he was bound to make those exceptions because of his want of power to declare slavery at an end except as a war measure.”

When Senator James Grimes of Iowa asked a question, Johnson responded, “Does he mean to say that you cannot raise a black man and get him into the service of the United States without setting free his wife and his children, no matter where they are? Has that been found true in the past?” Grimes responded that it had been true, even in Maryland, that “colored men object to going into the service because they say they are unwilling to leave their families—their wives and little ones who are dear to them—still in slavery, to be thrust hither and yon, carried out of the State or transferred to some other master, while they are serving the country and helping to hold up its flag.” Johnson declared that more than four thousand slaves had been recruited in Maryland within the last year, and he objected to other states, such as Massachusetts, recruiting men in states like Maryland and having it counted against their quotas.

Johnson also insisted that he was satisfied “that we are abundantly able to support the Government without violating the Constitution” by interfering in the domestic institutions of states not in rebellion. On the specific issue of the amendment, Johnson said, “the bill provides that a slave, enlisted anywhere, no matter where he may be...is at once to work the emancipation of his wife and his children. He may be in South Carolina; and many a slave in South Carolina, I am sorry to say it, can well claim to have a wife, or perhaps wives and children, within the limits of Maryland. It is one of the vices and the horrible vices of the institution, one that has shocked me from infancy to the present hour, that the whole marital relation is disregarded.” If Congress passed the bill, Johnson continued, “you will find it very difficult to prove who has a wife, or how many wives he has.” The laws of many southern states prohibited marriage between slaves, and they lived together “but were never man and wife except in the eye of Heaven. How are you going to ascertain whether a man taken here in Virginia has a wife in Maryland? He will say so, and he will prove that the woman whom he claims to be his wife once associated with him. But that, according to our laws, is not marriage; that of course does not constitute husband and wife.” Johnson continued, “What contest there will be if you pass this law! There will be a dozen women claiming freedom: ‘I am the wife,’ and “I am the wife,’ and ‘I am the wife,’ and each will be able to prove it by precisely the same evidence,” which evoked laughter from some senators. Johnson mildly chastised, “Honorable senators are laughing at very grave matters.” When Senator William Pitt Fessenden of Maine suggested that a proviso could limit the operation to only one wife, Johnson asked, “But which is to be the one?” Johnson insisted that the regulation of marriages was entirely within the authority of the individual states and the federal government had no authority to interfere with state institutions.[1]

When the presiding officer asked for a vote, Senator John Sherman of Ohio declared that he wished to speak at more length than the Senate would want to give. The Senate agreed to adjourn to take up the issue again on February 1. After a postponement on February 1, Senator Sherman spoke for more than two hours on the bill and the proposed amendment on February 2. “If we induce them to incur the risk of death and wounds in war upon the promise of emancipation, and do not redeem that promise, we add perfidy to wrong. The soldier who has worn our uniform and served under our flag must not hereafter labor as a slave. Nor would it be tolerable that his wife, his mother, or his child should be the property of another.” He warned the Senate, “If you have not the power, or do not mean to emancipate him and those with whom he is connected by domestic ties, then in the name of God and humanity do not employ him as a soldier.... If I had doubts about the power to emancipate the slave for military service, I certainly would not vote to employ him as a soldier.”[2] The Senate continued to discuss the bill and offer amendments periodically through February and March, but the bill never passed the Senate.[3]

On January 5, 1864, Senator Garrett Davis (1801-1872) of Kentucky introduced a series of resolutions denouncing the Lincoln administration for taking unconstitutional actions. He accused President Lincoln of destroying the constitutional rights of both northern and southern civilians and attempting to “subjugate” and “revolutionize” the South by abolishing slavery. He called on conservatives to elect delegates to a national convention that would negotiate an end to the war.

In response to Davis’s resolutions, Senator Henry Wilson introduced a resolution calling for the expulsion of Davis from the U.S. Senate. Paraphrasing but misrepresenting one of Davis’s resolutions, Wilson declared that Davis sought “to incite the people of the United States to revolt against the President...and to take the prosecution of the war into their own hands.” In response, Davis insisted that Wilson had presented “a garbled version of my resolution.” He observed that if anyone dared question the measures of the Republican majority, he was “branded and denounced by them as disloyal, as a traitor.” Davis insisted that the minority had both the right and the responsibility to criticize the majority.

Some Republican Senators, including William Pitt Fessenden of Maine and John P. Hale of New Hampshire, defended Davis’s right to speak and preferred to answer his allegations rather than censor him. Lazarus Powell of Kentucky, whom Davis had sought to expel for disloyalty in 1862, insisted that Davis had introduced his resolutions out of motives of “love of country.” The Republican majority quickly realized they did not have the two-thirds majority required to expel Davis, and Jacob Howard of Michigan proposed to censure him by a simple majority vote. Republican Henry S. Lane of Indiana found the idea of censure even more repulsive, declaring that it would do more to silence free speech in the Senate than the caning of Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts in 1856. On January 28, Wilson requested permission to withdraw his resolution of expulsion against Davis.

William Sprague IV (1830-1915) was born in Rhode Island. His uncle and namesake William Sprague III (1799-1856) was governor of Rhode Island (1838-1839) and U.S. Senator (1842-1844). The younger Sprague’s education was cut short when his father was murdered in 1843, and he began to work in the family textile business, the A & W. Sprague Manufacturing Company. He became a partner in the company when his uncle died in 1856. In 1848, he joined the Rhode Island militia and within three years was the colonel of his regiment. In 1860, he won election as Governor of Rhode Island, making him the youngest governor of a state at that time and earning him the nickname “boy governor.” He served as governor from 1860 to 1863 and strongly supported the Lincoln administration and the Union war effort. He participated in the First Battle of Bull Run as an aide to General Ambrose E. Burnside and during the battle had his horse shot out from under him. He was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1863, a position he held until 1875. In 1863, he married Kate Chase (1840-1899), daughter of Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase, and they had four children. The Panic of 1873 injured his business severely, and he and his wife divorced in 1882. The following year, he married Dora Inez Calvert (1859-1938) of West Virginia. After the mansion he had built in 1863 was destroyed by fire in 1909, they moved to Paris. During World War I, they offered their apartment as a convalescent hospital for the wounded. At his death, he was the last surviving Senator who had served in the Civil War.

William D. Ely (1815-1908) was born in Hartford, Connecticut, and graduated from Yale College in 1836, as a third-generation graduate. He studied law at the New Haven Law School and after a year of travel in Europe gained admission to the Connecticut bar in 1843 and the U.S. Supreme Court bar in 1847. In 1854, he married Anne Crawford Allen of Providence, Rhode Island, and they had two children. In 1860, he also purchased a cotton mill in Providence. He also authored several books on colonial history. When he died in 1908, he was Yale’s oldest living alumnus.

Condition: Flattened mail folds and mounting residue on verso along the right edge.

[1] The Congressional Globe, January 28, 1864, 394-97.

[2] The Congressional Globe, February 2, 1864, 438-39.

[3] On February 24, 1864, President Lincoln signed into law “An Act to amend an Act entitled ‘An Act for enrolling and calling out the National Forces, and for other Purposes,’ approved March third, eighteen hundred and sixty-three.” Section 24 of that act provided “That all able-bodied male colored persons, between the ages of twenty and forty-five years, resident in the United States, shall be enrolled according to the provisions of this act, and of the act to which this is an amendment, and form part of the national forces; and when a slave of a loyal master shall be drafted and mustered into the service of the United States, his master shall have a certificate thereof, and thereupon such slaves hall be free; and the bounty of one hundred dollars, now payable by law for each drafted man, shall be paid to the person to whom such drafted person was owing service or labor at the time of his muster into the service of the United States. The Secretary of War shall appoint a commission in each of the slave States represented in Congress, charged to award to each loyal person to whom a colored volunteer may owe service a just compensation, not exceeding three hundred dollars, for each such colored volunteer...and every such colored volunteer on being mustered into the service shall be free.” The act said nothing about the mothers, wives, or children of slaves drafted or volunteering for military service.