Click to enlarge:

Select an image:

“… until that moment I did not suppose he could have been forced to Vote for Genl Jackson.… I might ask the Gentleman from North Carolina (Mr Saunders) if he does not know some, who made earnest and solem appeals to members who were uncommitted, saying, save the Nation, save the Nation, by the election of Mr Adams, and who are now to be found arrayed among the foremost of the opposition”

In this letter to the editors of the Daily National Intelligencer, Maryland governor Joseph Kent attacks a “false & scurrilous” publication by R[omulus] M[itchell] Saunders regarding the 1824 election, asking them to publish a “correction.” An excerpt from a letter Kent had written in May 1827 characterized Congressman Saunders, a supporter of William Crawford, as anxious that the election be settled on the first ballot so that North Carolina would not “be forced to vote for” Andrew Jackson.[1] In 1827, Saunders vehemently denied Kent’s recollection and denounced the governor and the newspapers that had published his charge.

[1] Daily National Intelligencer (Washington, DC), July 21, 1827, 2:3. Previously published in Phenix Gazette (Alexandria, VA), July 20, 1827, 3:1, which copied it from The Commentator (Frankfort, KY), July 7, 1827, 3:1-2.

[ANDREW JACKSON].

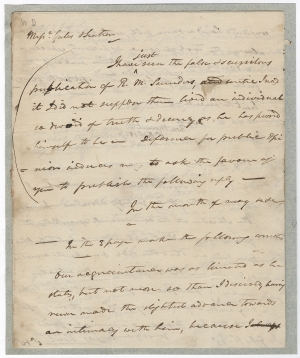

Joseph Kent, Autograph Letter Signed, to Joseph Gales Jr. and William W. Seaton, October 6, 1827, Rose Mount, Maryland. 7 pp., 8 x 9⅞ in. Published in the

Daily National Intelligencer (Washington, DC), October 8, 1827, 3:1.

Inventory #27455

Price: $1,500

Complete Transcript

Messrs Gales & Seaton

I have just seen the false & scurrilous publication of R. M. Saunders, and until I read it I did not suppose there lived an individual so devoid of truth & decency as he has proved himself to be. Deference for public Opinion induces me to ask the favour of you to publish the following reply

In the month of May &c &c

In the 3 page make the following correction

Our acquaintance was as limited as he states, but not more so than I desired, having never made the slightest advance toward an intimacy with him, because I considered him a vain, silly, unhappy tempered man, always the tool of some aspirant, expecting no doubt, in the event of their success, the full benefit of his intemperate zeal.

Insert the piece on Monday / Date it Rose Mount / 6th Octr 1827

My Dear Sir

I regretted that you were out when I called at the office yesterday noon. In making the alteration at the commencement of my letter to you, I have worded it awkwardly. Substitute what you find on the other side & make the correction as desired on the 3d page. My situation makes it painful to have a newspaper controversy with any one & my funds insist on my refusing at this time to make it a personal affair. / Yours very truly Jos: Kent 6th Oct

Jos. Gales Jr Esqr

Messrs G & S

I have seen the false and scurrilous publication of R. M. Saunders, and deference for public opinion induces me to request you to publish the following reply.

Until I read Mr S. publication I had not supposed that an individual lived so devoid of truth and decency as he has proved himself to be.

In the month of May last I wrote a letter to a private Gentleman, an old Congressional friend in Frankfort in reply to one received from him, not designed for publication as every candid man would at once perceive as well from its stile, as its subject, and he has since apologized for a portion of it finding its way into the public journals.

In this letter in consequence of Genl Saunders’s own zealous part in the H of Representatives the preceding winter (the lot of all new converts) I adverted to a conversation he held with me the morning of the Presidential election, every word of which I aver to be the fact and I throw back upon Genl Saunders the vulgar epithet he has had the audacity to apply to me.

But a few minutes before the election, Genl Saunders approached the fire place at the south end of the room, taped me on the arm, drew me aside & used the strong language I have ascribed to him, & farther I saw no Individual after the election better pleased than Genl S. appeared to be in consequence of being relieved as I supposed from the dilemma in which he had considered himself placed.

Genl S. approaching me in the manner he did surprised me and caused me to recollect the conversation (which I repeated to a friend a day or two afterwards) because until that moment I did not suppose he could have been forced to Vote for Genl Jackson. Our acquaintance was as limited as Genl S. states, but not more so than I desired, having never made the slightest advance towards an intimacy with him, because I considered him a vain, weak & passionate man, always the tool of some aspirant, expecting perhaps in the event of their success the full benefit of his intemperate zeal.

Genl S. only wanted to know whether Mr Adams could be elected on the first ballot to save him the necessity of electing Genl Jackson!!! His attachment to Genl J. must have been as strong as his inclination to oblige his constituents, when both united coud not render him willing to encounter the trouble of a second ballot.

How much Genl S. regards his veracity you may judge when he calls the redeeming a pledge made by Coln Mitchell to his constituents, “a suicidal morality of my teaching.” Unfortunately for him, I had but little if any conversation with Coln M. about the Presidential election whilst it was pending, so little that I did not know until I had counted the ballots in the H. of Representatives how the Coln had intended to vote.

Genl S. sensitivity on the present occasion is somewhat surprising, as he was charged with the same remarks I have attributed to him by Mr F. Johnson in the H of R, as will be seen by the following extract from his speech delivered in February last—“The Secretary of State did vote for Mr Adams and I might ask many who are now arrayed against the administration if they would not have done so? I might ask the Gentleman from North Carolina (Mr Saunders) if he does not know some, who made earnest and solem appeals to members who were uncommitted, saying, save the Nation, save the Nation, by the election of Mr Adams, and who are now to be found arrayed among the foremost of the opposition”

The language Mr Johnson attributes to Genl S is stronger than what I have used, and is said to have been addressed to the uncommitted portion of the House, and Genl S. is again mistaken in supposing that he (Mr Johnson) derived his information from me, for unhappily for him, not one word either orally or in writing was passed from me to Mr Johnson on the subject.

Jos: Kent / Rose Mount / Octr 1827

Historical Background

Voting in the presidential election of 1824 occurred between October 26 and December 2. None of the four main Democratic-Republican candidates could muster a majority of the popular or electoral votes. Andrew Jackson of Tennessee led with 41.4 percent of the popular vote and carried 12 states with 99 electoral votes, 32 shy of victory. John Quincy Adams of Massachusetts attracted 30.9 percent of the popular vote and carried 7 states. William H. Crawford of Georgia received 11.2 percent of the popular vote but carried only 2 states, and Henry Clay of Kentucky garnered 13 percent of the popular vote and carried 3 states. The Twelfth Amendment required the House of Representatives to select from among the three candidates who received the most electoral votes, thus eliminating Henry Clay.

Both Joseph Kent and Romulus M. Saunders were in Congress when the contested election of 1824 reached the House. Kent represented Maryland, and Saunders North Carolina. In the contingent election held in the House on February 9, 1825, the 24 states each received one vote, so 13 were needed to win. John Quincy Adams won the votes of 13 states, including Maryland (with 5 of the state’s 9 representatives), Jackson of 7, and Crawford of 4 (including North Carolina, supported by 10 of the state’s 13 representatives).

Since General Andrew Jackson received the most popular and electoral votes, they expected him to be elected by the House. The 1828 presidential campaign began immediately. Three years later, the election was still a matter of dispute, as this letter makes clear.

On September 6, 1827, the Daily National Intelligencer republished from the Raleigh Register of North Carolina an extract of a letter from Maryland Governor Joseph Kent to a friend in Kentucky. Kent complained of the violent opposition to John Quincy Adams’ administration, and of Saunders’s attack on Henry Clay in the last session of Congress. Kent found it particularly odd since, in 1824, Saunders preferred Adams to Jackson. Kent added, “not ten minutes before the election of President by the House of Representatives, Gen. Saunders came to him, with anxious countenance, discovering deep concern, and using these emphatic words: ‘I hope to God you may be able to terminate the election on the first ballot, for fear we from North Carolina may be forced to vote for Gen. Jackson.” The editors of the Raleigh Register continued, “We have a communication from Gen. Saunders, denying the truth of the above statement of Governor Kent, in terms the most positive; declaring that he was decidedly opposed to the election of Mr. Adams, and that, after Mr. Crawford, Gen. Jackson was his choice—a fact which, he says, was well known at the time to all his political friends in Congress.” The Raleigh Register refused to publish Saunders’s entire letter because it charged them with “being subsidized, subservient to the will of the Secretary of State” and “uses a coarseness of language towards Governor Kent to which we cannot give publicity.”[1]

The editors of the Daily National Intelligencer offered “speedy insertion” to Saunders’s letter if he would send it to them and declared that “before he became bewitched with faction,” Saunders was “our personal friend.”[2] On October 6, the Intelligencer published Saunders’ August 20 letter responding to the publication of the extract from Kent’s letter. In the lengthy letter, Saunders described Kent as “one who I had always viewed as concealing under a plausible exterior, the secret, but deadly enmity of a viper.” He went on to declare that “From the commencement of the late Presidential contest, to its termination, I harbored but one feeling, and expressed but one language—a preference for William H. Crawford, and the most positive hostility to John Q. Adams.” Saunders went on to declare that members of Congress generally knew that “Colonel Mitchell [of Maryland] also, by a kind of suicidal morality, (probably of Governor Kent’s teaching) and upon whom the vote of Maryland depended, would first vote for Mr. Adams, afterwards for General Jackson.” Saunders concluded his letter by accusing Kent of attempting to “save those with whom he acted, from the day of account and retribution” and described them as “Wicked and unhappy men! who seek their private safety in opposing public good. Weak and silly men! who vainly imagine that they shall pass for the nation, and the nation for a faction; that they shall be judged in the right, and every one who opposes them in the wrong.”[3]

In a separate column, the editors reprinted a short piece from the Baltimore Patriot, printing a letter from a North Carolina constituent: “Whatever may have been Mr. Saunders’s professions, pretensions, or preferences, made to Governor Kent, to the Editors of whom he speaks, or to any other person or persons, after he left his District is not for me to say; but, before the election for President took place, when Mr. Saunders was before the People as a candidate for Congress, he told his constituents, that, in case he failed to obtain Mr. Crawford, his first choice, he would unhesitatingly take up Mr. Adams as his second.”[4]

In a third piece, the editors of the Intelligencer wrote of Saunders’s letter: “His general vituperation, in the style of the kennel press, applied to the independent presses of the country, appears to us to be entitled to no more respect than the miserable effusions which deluge the country from that press.” “With respect to Governor Kent,” they continued, “he is abundantly able to protect his own character.” Two days later, they published this letter by Kent.[5]

Joseph Kent(1779-1837) was born in Maryland and studied medicine. He became a physician in 1799, and purchased a plantation near Bladensburg, Maryland, that he named “Rose Mount.” He settled there around 1807 and continued to practice medicine and farm. In 1807, he entered the Maryland militia as a surgeon’s mate. He rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel and was made a full surgeon in 1809, but he resigned the same year. He won election as a Federalist to the U.S. House of Representatives, where he served from 1811 to 1815. He again won election to Congress in 1818 as a Democratic-Republican, serving from 1819 until resigning in January 1826. He resigned to take office as Governor of Maryland, a position he held from January 1826 to January 1829. He was elected as a Republican to the U.S. Senate, though he later became a Whig, and served from 1833 until his death.

Romulus Mitchell Saunders (1791-1867) attended the University of North Carolina, studied law and was admitted to the bar in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1812. After serving in the North Carolina legislature for six years, he was elected as a Republican to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1820, reelected as a Crawford Republican and again as a Jacksonian, serving from until 1827. He was the attorney general of North Carolina from 1828 to 1831 and judge of the superior court from 1835 to 1840. He again won election to Congress as a Democrat and served from 1841 to 1845. Saunders was Minister to Spain from 1846 to 1849, before returning and again serving in the North Carolina legislature and as a judge.

National Intelligencer (1800-1870) was a prominent newspaper published in Washington, DC. In 1800, Thomas Jefferson, then vice president and a candidate for the presidency, persuaded Samuel Harrison Smith, the publisher of a Philadelphia newspaper, to open a newspaper in Washington, the new capital. Smith began publishing the National Intelligencer, & Washington Advertiser three times a week on October 31, 1800. In 1809, Joseph Gales (1786-1860) became a partner and took over as sole proprietor a year later. From 1812, Gales and his brother-in-law William Winston Seaton (1785-1866) were the newspaper’s publishers for nearly fifty years. From 1813 to 1867, it was published daily as the Daily National Intelligencer and was the dominant newspaper of the capital. Supporters of the administrations of Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe, Gales and Seaton were the official printers of Congress from 1819 to 1829. From the election of Andrew Jackson to the 1850s, the National Intelligencer was one of the nation’s leading Whig newspapers, with conservative, unionist principles.

Condition: General toning; glued to scrapbook page; some staining from glue, not affecting text.

[1] Daily National Intelligencer (Washington, DC), September 6, 1827, 3:2.

[3] Daily National Intelligencer (Washington, DC), October 6, 1827, 2:4.