Other Women's History and First Ladies Offerings

More...

Other Great Gifts Offerings

More...

- Abraham Lincoln Signed Check to “William Johnson (Colored)”—Who Accompanied the President to Antietam and Gettysburg

- FDR’s First Inaugural Address in the Midst of the Great Depression

- Albert Einstein by Marc Mellon

- President Harry S. Truman Signs Potsdam Declaration Demanding Japanese Surrender for Himself, Winston Churchill, and Chiang Kai-shek

- Earliest Known Printing of “Tikvatenu” [Our Hope – the origin of “Hatikvah”] Inscribed by Author Naftali Herz Imber to Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, the “revivalist of the Hebrew language”

- Winston Churchill by Marc Mellon

- George F. Root’s Autograph Sheet Music for “The Battle-Cry of Freedom!”

- Continental Congress Declares Independence – on July 2, 1776

- Thomas Jefferson Transmits the First Patent Act to Governor of New York George Clinton, Who Later Replaced Aaron Burr as Jefferson’s Vice President

- Unique Inscribed Set of John Marshall’s Life of George Washington, With Joseph Story Letter to the Daughter of the Late Associate Justice Henry Brockholst Livingston, Conveying Marshall’s Thanks and Noting That He Will Be Sending to Her These Very Books

- President Woodrow Wilson Asks Congress for a Declaration of War

- President Wilson Urges Americans to Support the “Stricken Jewish People” of Europe During World War I

- “Black Sam” Fraunces as Steward of George Washington’s Presidential Household

- Civil War “The Union Forever” Flag Made by Philadelphia Sailmaker, ca. 1861

- Lyndon B. Johnson Signing Pen for Voting Rights Act of 1965

- Early Printing of the U.S. Constitution, in American Museum—One of the First Two Magazine Printings of the Constitution

- George Washington’s Famous Letter to American Roman Catholics: A Message of Thankfulness, Patriotism, and Inclusiveness

- Thomas Jefferson Pays Import Duty on Famous Louis Chantrot Obelisk Clock

- George Washington: Rare 1777 Revolutionary War Hand Colored Engraving

- Theodore Roosevelt, Furious with Cuba's "Pointless" 1906 Revolution

- Harry S. Truman on His 1948 Proclamation Recognizing Israel

- A Week After Cuban Missile Crisis, JFK Asks Treasury Secretary Dillon About the Possibility of a Run on Gold if the Crisis Had Lasted Longer or Involved a Total Blockade

- Two months Before Declaring Israel’s Independence, Ben-Gurion Counters American Backpedaling and Pushes to Start the Temporary Government

- Amelia Earhart and Richard E. Byrd—Aviation Pioneers in Signed Group Photo

- Aviation Pioneer Amelia Earhart Returns from European Tour with Publisher Husband

- Masonic Documents: James P. Kimball archive of master Mason, geologist, and Director of the United States Mint - with superb engravings

- FDR’s Personal Copy of 1934 Textile Industry Crisis Board Report Countersigned by Secretary of Labor Francis Perkins, the First Woman Presidential Cabinet Member

- J.E.B. Stuart Writes to Legendary Confederate Spy Laura Ratcliffe

- David Ben-Gurion ALS—Preventing a War between the Religious and the Secular in Early Israel

- Debating the Bill of Rights Amendments in 1789

- President John Quincy Adams’ Remarks & Toast Commemorating William Penn’s Landing

- Connecticut Governor’s Proclamation Calling for a Day of Thanksgiving to Commemorate the Defeat of the French in Canada, and the Taking of Quebec

- The Gettysburg Address – New York Semi-Weekly Tribune First Day of Printing

- Vibrant Print of Fifteenth Amendment Celebrations

- President Jefferson Sends, Rather than Delivers, His First State of the Union

- 1915 Women’s Suffrage Poster

- Jackie Robinson says a talk radio host “needs to do a lot of soul searching.”

- Whig Presidential Nominee William Henry Harrison to Daniel Webster

- “George Washington” - Keith Carter Photograph

- 1778 Muster List, Including Rejected African American Recruit

- Large 1801 Folio Engraving of Thomas Jefferson as New President

- Nine Months of a Hawaiian Missionary Newspaper, With the First Report of King Kamehameha III’s Death and Perry’s Mission to Japan

- Ben-Gurion to Moshe Sharett on Sharett’s Resignation as Foreign Minister

- Acquittal of Printer John Peter Zenger in Colonial New York Establishes Foundation for American Freedom of the Press

- Prang & Co. Broadside with Maps of Early Civil War Hotspots

- President Theodore Roosevelt Questions Coal Monopolies and Contradictions in Report from Interstate Commerce Chairman

- Rare 1870 Yale University Summer Boat Races Broadside

- Susan B. Anthony Plaster Relief Medallion Copyrighted by Her Sister

- Arthur Ashe’s United Negro College Fund Benefit Silver Bowl Trophy

- Golda Meir Stresses the Need to Settle New Immigrants

- “John Bull and the Baltimoreans” Lampooning British Defeat at Fort McHenry in Baltimore Following their Earlier Success at Alexandria

- Ben-Gurion Attempts to Convince the Israeli Government to Attack Jordan, After Jordan Violated the Cease-fire Ending the Six Day War

- Boston Newspaper Publishes Former Governor Hutchinson’s Letters

- Inventor Thomas A. Edison Responds to His Son’s Note About a Speaking Request

- Golda Meir Invites an American Semiconductor Pioneer to an Israeli Economic Conference

- Madison’s Optimistic First Message to Congress: A Prelude to the War of 1812

- Bronze Bas Relief Portrait of Theodore Roosevelt: “Aggressive fighting for the right is the greatest sport the world affords”

- Early Printing of a Bill to Establish the Treasury Department

- Harry Hines Woodring Political Archives and Related Material

- Congressmen Who Signed Thirteenth Amendment Abolishing Slavery

- Anticipating Prohibition Repeal

- Theodore Roosevelt Rough Rider Doll

- Eleanor Roosevelt Asks Pennsylvania Educator to Serve as Chair of Local Women’s Crusade

- Ben-Gurion Calls for a Jerusalem Home for the Bible Society: “every spiritual idea, for it to exist and exert influence, needs a physical structure, too, a central home…”

- Lucy Stone Thanks Suffragist Who Later Led Effort for Women’s Suffrage in Hawaii for Donation

- Pulling Down New York’s Statue of King George III

- A Ruff-Necked Hummingbird by Audubon

- Masonic Apron, Neck Sash & Medal of U.S. Mint - California Gold Refiner James Booth, with a Lithograph of Him

- Calvin Coolidge Appoints Trustee of the National Training School for Girls

- Harvard’s 1791 Graduating Students and Theses, Dedicated to Governor John Hancock and Lieutenant Governor Samuel Adams

- Pennsylvania Deputy Governor Urges General Assembly to Resist French Expansion in North America in Early Stages of the French and Indian War

- Lucy Stone Promotes Bazaar to Suffragist Who Later Led Effort for Women’s Suffrage in Hawaii

- New York Times Carriers’ Address Reviews the Year 1863 in Bad Verse, Including Freeing of Russia’s Serfs, and the Battle of Gettysburg

- Eleanor Roosevelt Thanks Former State Senator for Article to Assist Women in Monitoring Polling Places

- Hillary Clinton Thanks Doctor for Policy Change to Allow Fathers to Be in Delivery Room for Caesarean Sections

- John Marshall’s “Life of George Washington”

and Companion Atlas with Hand-colored Maps

- President Franklin D. Roosevelt Thanks for a “Heartening” Telegram Received September 27, While FDR was Trying to Prevent Hitler from Starting War

- Senator Sprague of Rhode Island Writes About Fascinating Debates in Congress Involving Freedom for the Families of African American Recruits and the Limits of Free Speech in the Senate

- Gerald Ford Defends His Early Commitment to Civil Rights

- Picasso Anti-War Image Used to Promote Vietnam War Protest

- 16 x 20 Inch Photograph of St. Augustine, Florida, African American Cart Driver

- Future Supreme Court Justice Benjamin Cardozo: “I am alone in the world now.”

- Anthony C. McAuliffe Writes Amidst Tests of Atomic Bombs at Bikini Atoll in 1946

- Hoover Tells a Key Aide that Lindbergh Baby Kidnapping Occupies FBI in New York

- Mercury Astronaut Gordon Cooper’s Signed “Bioscience Data Plan” for Conducting Vital Biomedical Research on the Impact of Space Flight on the Human Body

- Ohio Reformers Use Rhode Island’s Dorr Rebellion

to Justify Their Own Behavior

- 1790 Massachusetts Newspaper Discussing Nantucket Whalers

- Mark Hopkins, Famed Educator and the Longest Serving President of Williams College, Preparing to Lecture at the Smithsonian Institute

- Future Hero of Little Round Top Advises a Friend on Getting a Leave of Absence

- A Harlequin Duck by Audubon

- Alex Haley Signed Check

- New England Factory Life

- Rebel Deserters Coming within the Union Lines

- Advertisement for Temperance Restaurant in New York City

- Seesaw - Gloucester, MA - Drawn by Winslow Homer

- The Statue of Liberty

- Christmas Presents

- The Army of the Potomac Arriving at Yorktown from Williamsburg

- (On Hold) The U.S. Constitution – Very Rare Printing on the Second Day of Publication

|

|

|

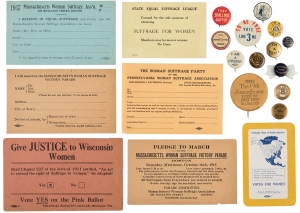

Women’s Suffrage Pledge Cards and Pins |

Click to enlarge:

This extensive collection of suffrage cards and pins represents the efforts of female and male suffragists and anti-suffragists across several states between 1912 and 1920. [WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE].

Archive of 20 Women’s Suffrage Pledge Cards and Pins, 1912-1920.

Inventory #27260

SOLD — please inquire about other items

Items and Excerpts

-

Political Equality League, Milwaukee, WI, “Give JUSTICE to Wisconsin Women” card, 1912. “Shall Chapter 227 of the laws of 1911 entitled, ‘An act to extend the right of Suffrage to women,’ be adopted? / Vote YES on the Pink Ballot” In 1911, the Wisconsin legislature passed a suffrage bill to be voted on by a statewide referendum in November 1912. The women’s suffrage referendum failed by a 63 percent to 37 percent margin. In June 1919, Wisconsin became the first state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment.

-

Parade Committee, Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association, Boston, “Pledge to March in the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Victory Parade” card, 1915. “Saturday Afternoon, October 16th, 1915 / For information watch the Woman’s Journal and the daily papers. / No automobiles or carriages will be included in the parade. / All Suffragists from Everywhere are invited to march.”

-

Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association, Boston, ca. 1915. “I will march in the MASSACHUSETTS WOMAN SUFFRAGE VICTORY PARADE.” The October 16 parade in Boston included approximately 8,500 marchers and 32 bands. Among its most famous participants was Helen Keller. Many marchers carried yellow balloons or yellow banners, the color of the suffrage movement. Its banners urged the 200,000 observers to vote yes on November 2. The marchers paused before the State House, where Democratic Governor David I. Walsh bowed, and anti-suffragists released red balloons in silent protest. At City Hall, the flamboyant Democratic Mayor James Michael Curley reviewed the parade. Both Walsh and Curley supported women’s suffrage. The women suffragists held a mass meeting in the Mechanic’s Building immediately after the parade.

-

Woman Suffrage Party of the Pennsylvania Woman Suffrage Association, Membership Card, ca. 1915. “[Name] believing that women as well as men should vote, hereby join the Woman Suffrage Party, with the understanding that it requires no dues, is non-partisan in character, and that it does not interfere with my regular political affiliations.”

-

Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association, Boston, Membership Card, 1917. “I BELIEVE IN EQUAL SUFFRAGE, and hereby join the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association (no dues). / To be signed by men or women over 21 years of age.”

-

State Equal Suffrage League, 2 pp., [Virginia?], n.d. “State Equal Suffrage League / Formed for the sole purpose of obtaining / SUFFRAGE FOR WOMEN / Members may be men or women. No dues.”

-

National Woman Suffrage Publishing Company, “Suffrage Map of North America,” ca. 1917, New York, NY. “White-Full Suffrage / Gray—Partial Suffrage / Dotted—Presidential Suffrage / Black—No Suffrage / VOTES FOR WOMEN”

Suffrage Pins

-

“I’m a Voter,” ca. 1915. Suffragist Jeannette Rankin (1880-1973) of Montana developed the idea of an “I’m a Voter” button for women from states with women’s suffrage to wear at the Panama–Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco to “constantly remind women from the east of the boon they are missing.”[1] The following year, Rankin became the first woman to hold a federal office, when she was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives.

-

“I Am A Citizen,” Rochester, [NY?] “I’m a Voter,” around the state seal of Missouri. The National American Woman Suffrage Association held its Golden Jubilee Convention in St. Louis, Missouri, in March 1919. All Missouri women at the meeting received a button with the words “I Am a Voter” to celebrate the passage of the presidential suffrage bill by the Missouri legislature. On April 5, Governor Frederick D. Gardner signed the bill into law. Three months later, the governor called a special session of the legislature, and Missouri became the eleventh state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment.

-

“Ballots for Both” [ca. 1916] This pin features the text “Ballots for Both,” coined by Dr. Eleanor Hiestand-Moore (1859-1923), a Pennsylvania suffragist. Hiestand-Moore won a slogan contest sponsored by the National American Woman’s Suffrage Association with this entry that countered the view that women’s suffrage would deprive other groups of their voting rights.

-

“Equal Suffrage Amendment / Vote Yes Scratch No,” Steiner Company, St. Louis, MO.

-

“To Be Free Vote Like Me / 3,” [Ohio, 1914?] On November 3, 1914, male voters in Ohio rejected Amendment 3, which would have amended the state constitution to allow women to vote by a margin of 39.3 percent in favor of the amendment to 60.7 percent against the amendment.

-

“Vote Citizenship Suffrage Amendment E” [New York, NY, ca. 1918] In November 1918, 64 percent of male voters in South Dakota approved Amendment E, which granted rights of suffrage to women but limited these rights to naturalized citizens. The wording of the amendment effectively quieted opponents by linking anti-suffrage sentiment with sympathy for Germany, the principal American foe in World War I. South Dakota became the seventeenth state to grant full suffrage to women.

-

“Vote for Amendment 8” On October 10, 1911, California voters narrowly approved Constitutional Amendment No. 8, the women’s suffrage amendment. Out of more than 246,000 votes cast, the amendment was approved by a margin of 3,587 votes.

-

“Women’s War Savings Service,” Whitehead & Hoag Co., Newark, NJ, ca. 1918. The War Savings Service was related to the purchase of War Savings Stamps. The U.S. Treasury began issuing War Savings Stamps in late 1917 to help fund American participation in World War I. Women’s support of the war effort helped to ensure success in the suffrage movement.

-

“Men’s Equal Suffrage League” Max Eastman and Oswald Garrison Villard organized the Men’s Equal Suffrage League in New York in 1910. Similar groups formed in Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Illinois that same year, and male suffragists in several other states organized Men’s Equal Suffrage Leagues between 1911 and 1916.

-

Suffrage Pin: “Under The 19th Amendment I Cast My First Vote / Nov. 2nd, 1920” With the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment by Tennessee on August 18, 1920, the amendment became part of the United States Constitution, and 26 million American women were enfranchised for the 1920 presidential election. Approximately 36 percent of eligible women (roughly 9.4 million) voted in that election, compared to 68 percent of eligible men. By 1960, a greater proportion of women than men were voting in presidential elections.

Anti-Suffrage Pins

-

“They Shall Not Suffer,” [Hyatt Mfg. Co., Baltimore, MD]

-

“Suffrage Means Prohibition,” Whitehead & Hoag Co., Newark, NJ. Perhaps mistaken as a pro-suffrage pin because the Women’s Christian Temperance Union formally endorsed women’s suffrage in 1881, the liquor industry campaigned against women’s suffrage in the early twentieth century by employing the slogan on this pin.

Historical Background

On November 2, 1915, New York, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts all held referenda on women’s suffrage. The referenda failed in all three states. In New York, male voters rejected suffrage for women by a majority of 58 percent. In Pennsylvania, 53 percent of the men who voted rejected the proposal, while in Massachusetts, 64.5 percent of voters opposed women’s suffrage. In October, New Jersey had also rejected women’s suffrage by a majority of 58 percent.

Undaunted, the American Woman Suffrage Association continued to press for women’s suffrage. When asked how long the triple defeat would delay a new attempt to win another state for women’s suffrage, Anna Howard Shaw replied, “Until we can get a little sleep. The fight will be on tomorrow morning—on forever, until we get the vote.” Suffragists later used American participation in World War I as a reason that men should vote for suffrage.

In March 1917, the New York legislature granted the suffragists a second chance to submit their amendment to the voters. On November 6, 1917, men in New York went to the polls to decide whether women should have the right to vote. The referendum passed by a vote of 703,129 to 600,776 (54 to 46 percent). Although the referendum failed upstate by 1,570 votes, New York City approved it by a margin of 103,863. Suffragist leader Carrie Chapman Catt later declared the campaign in New York State as the decisive battle of the American woman suffrage movement, leading to the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

In his address to the U.S. Senate on September 30, 1918, President Woodrow Wilson also used the war as a reason to support universal suffrage: “I regard the concurrenceof the Senate in the constitutional amendment proposing the extension of the suffrage to women as vitally essential to the successful prosecution of the great war of humanity in which we are engaged.”

In June 1919, Congress passed a proposed Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and submitted it to the states for ratification. The proposed amendment prohibited the denial of the right to vote on the basis of sex. The necessary three-quarters of the states ratified the amendment by just over a year later, in August 1920. When Tennessee became the thirty-sixth state to ratify it, the amendment became part of the Constitution, culminating seventy-two years of effort on behalf of women’s suffrage.

Women in Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and New Jersey, like those in eighteen other states, had to await the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to obtain the right to vote. Ironically, Pennsylvania became the seventh state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment, on June 24, 1919, and a day later, Massachusetts became the eighth. New Jersey became the twenty-ninth state to ratify on February 9, 1920.

Condition: Some chips and edge tears not affecting text.

[1]The Leavenworth Times (KS), May 6, 1915, 4:4.

|