Click to enlarge:

Select an image:

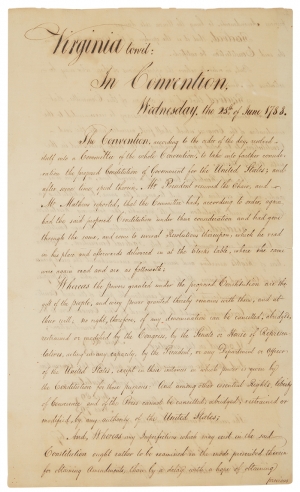

Official and attested copy of Virginia’s Ratification of the U.S. Constitution, together with a proposed Declaration of Rights and twenty other proposed amendments to the Constitution, signed by Virginia Ratification Convention President Edmund Pendleton and Secretary John J. Beckley. It is one of only three known surviving sets that the Convention ordered to be engrossed and sent to the other state executives or legislatures. The Convention also ordered that a set be sent to the Confederation Congress.

[U.S. CONSTITUTION, BILL OF RIGHTS].

Edmund Pendleton, Manuscript Document Signed, Extracts of Proceedings of Virginia Ratification Convention, June 25-27, 1788. Also signed and attested by John Beckley as secretary. Paper watermarked “Posthorn GR”; countermarked “IV.” 14 pp., 8¾ x 14¾ in.

Inventory #27341

PRICE ON REQUEST

Historical Background

The Virginia Ratification Convention—also known as the Virginia Federal Convention—convened at the State House in Richmond on June 2, 1788. The 170 delegates included many of the leaders of the state, including James Madison, Patrick Henry, George Mason, George Wythe, Edmund Randolph, James Monroe, Benjamin Harrison, Henry Lee, John Carter Littlepage, John Marshall, Humphrey Marshall, Burwell Bassett, Theodorick Bland, Bushrod Washington, and John Blair. On the first day, the Convention unanimously elected Edmund Pendleton as president and John Beckley as secretary. The Convention also ordered its official printer Augustine Davis to print 200 copies of the Constitution proposed by the Constitutional Convention, which had concluded in Philadelphia in September 1787.

Although the Articles of Confederation required that any change or amendment had to be the unanimous decision of all thirteen states, the Philadelphia Convention decided that ratification by only two-thirds of the states would be necessary. According to Article VII of the proposed Constitution, “The Ratification of the Conventions of nine States, shall be sufficient for the Establishment of this Constitution between the States so ratifying the Same.”

Only Rhode Island refused to send delegates to the Constitutional Convention or to consider its proposed frame of government; it became the last of the original states to ratify in May 1790, after the Constitution had been in operation for nearly two years. Eight other states had already ratified the Constitution, the most recent being South Carolina, which ratified it on May 23, 1788, ten days before Virginia’s delegates convened in Richmond.

The delegates who assembled in Richmond were sharply divided. James Madison, who had introduced the “Virginia Plan” at the Philadelphia Convention, led the Federalist faction. Madison also provided vital support for ratification as one of the three pseudonymous authors, with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, of The Federalist essays. Most were first published in New York newspapers between October 1787 and April 1788. That spring, all eighty-five essays were published in book form, which would have been available to the delegates in Virginia.

Patrick Henry, fearing federal encroachment on Virginia’s liberties and state government, led the Antifederalist delegates. His opposition to the government under the Constitution remained so zealous that he declined appointments as Secretary of State and as a justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. Henry’s control of the Virginia legislature also allowed him to thwart Madison’s election to the U.S. Senate, and Virginia sent William Grayson and Richard Henry Lee, two Anti-Federalist senators, to the First Congress. Madison was elected to the House of Representatives.

The Virginia Ratifying Convention met six days a week from June 2 to June 27, for a total of twenty-three sessions. After completing some preliminary business, the Convention devoted most daily assemblies to debating the Constitution in the Committee of the Whole, usually with George Wythe (signer of the Declaration, and Thomas Jefferson’s law instructor) serving as the chair. Although the Convention had initially resolved to have the entire Constitution read and discussed clause-by-clause before beginning debate, Patrick Henry delivered several discursive orations of up to three hours on the Constitution in general. Fellow Antifederalists George Mason (who had refused to sign the Constitution as a delegate to the Philadelphia Convention), James Monroe, and William Grayson supported Henry in the debates.

In addition to James Madison, key Federalist speakers included Edmund Randolph (who refused to sign as a Virginia delegate to the Philadelphia Convention, but supported its adoption by Virginia only months later), George Nicholas, Edmund Pendleton, Francis Corbin, John Marshall, and Henry Lee. Fewer than two dozen of the 170 delegates participated in the discussions of the Committee of the Whole.

The question of a Bill of Rights was a key component of the debate in the Virginia Ratifying Convention. Because Anti-Federalists feared federal encroachment and even tyranny, they refused to consider ratification without some essential guarantees of personal liberty and the sovereignty of the people. In contrast, Federalists, many of whom also wanted a Bill of Rights, favored ratifying the Constitution unconditionally, as proposed by the Philadelphia Convention, and then addressing the adoption of necessary amendments.

On June 24, the nineteenth day of the Convention, George Wythe proposed that the delegates “should ratify the Constitution, and that whatsoever amendments might be deemed necessary, should be recommended to the consideration of Congress which should first assemble under the Constitution, to be acted upon according to the mode prescribed therein.” Patrick Henry responded with a proposal “to refer a declaration of rights, with certain amendments to the most exceptional parts of the Constitution, to the other States in the Confederacy, for their consideration, previous to its ratification.”[1]

In the last speech before the vote on these resolutions on June 25, Edmund Randolph explained his change on ratification since he had refused to sign the Constitution in Philadelphia: “The suffrage which I shall give in favor of the Constitution, will be ascribed by malice to motives unknown to my breast. But although for every other act of my life, I shall seek refuge in the mercy of God—for this I request his justice only. Lest however some future annalist should in the spirit of party vengeance, deign to mention my name, let him recite these truths,—that I went to the Federal Convention, with the strongest affection for the Union; that I acted there in full conformity with this affection; that I refused to subscribe; because I had, as I still have, objections to the Constitution, and wished a free inquiry into its merits; and that the accession of eight States reduced our deliberations to the single question of Union or no Union.”[2]

The following day, both resolutions were voted on. The Committee of the Whole, with Edmund Pendleton presiding, rejected the Antifederalists’ resolution by a vote of 88 to 80. Then, between 2:00 and 3:00 p.m., the delegates voted to ratify the Constitution by a vote of 89 to 79.

After ratification, the Convention appointed a committee of five—Federalists James Madison, Edmund Randolph, George Nicholas, John Marshall, and Francis Corbin—to compose the official text of Virginia’s ratification. The full Convention adopted the document they submitted on the same day, and it appears on the third and fourth pages of this official transcription.

The Convention also appointed a committee of twenty members, including both Federalists and Antifederalists, to prepare recommended amendments. Chaired by George Wythe, the committee included the most prominent voices of the Convention, including Patrick Henry, Edmund Randolph, George Mason, James Madison, and James Monroe.

On the final day of the Convention, June 27, Wythe reported “such Amendments to the proposed Constitution of Government for the United States, as were by them deemed necessary to be recommended to the consideration of the Congress which shall first assemble under the said Constitution, to be acted upon according to the mode prescribed in the fifth article thereof.…”[3]

The Committee presented the amendments in two groups. The first twenty comprised “a Declaration or Bill of Rights asserting and securing from encroachment the essential and unalienable rights of the people,” and the second set of twenty proposed structural amendments to the Constitution. Both sets of proposed amendments closely reflected the work of an Antifederalist committee chaired by George Mason in the early days of the Convention.

The delegates to the Virginia Ratifying Convention thought they had become the ninth and necessary state to ratify the Constitution. They did not learn until later that New Hampshire’s Ratifying Convention had already approved the Constitution on June 21, 1788, giving New Hampshire the honor of becoming the necessary ninth state.

However, Virginia was the most populous and wealthiest of the thirteen original states, and without its approval, the new government of the United States under the Constitution would have had little chance of success. In addition, Virginia’s ratification had a crucial effect on the pivotal decision one month later by New York to ratify the Constitution.

Virginia was not the only state to ratify the Constitution with the understanding that amendments should or would be adopted almost immediately, ranging from South Carolina’s four to New York’s fifty-seven proposed amendments. However, Virginia’s proposed “Declaration or Bill of Rights” is most closely reflected in what became the federal Bill of Rights.

Postscript

On May 4, 1789, Madison proposed in the House of Representatives that they begin debate on a series of amendments to the Constitution to serve as a bill of rights. On June 8, Madison made a speech recommending a series of amendments, which was referred to a select committee of eleven. Under Madison’s guidance, the committee prepared an initial draft and presented it to the House on July 28. Some members of Congress found the committee’s proposal of revising the text of the Constitution itself to be confusing and ambiguous. Roger Sherman of Connecticut convinced the House to place the amendments at the end of the Constitution to leave the original document “inviolate.” On August 24, the House approved seventeen articles “in addition to, and amendment of, the Constitution of the United States of America.”

On September 9, 1789, the U.S. Senate approved a series of twelve articles, and a House-Senate Conference Committee resolved the differences by September 24. Congress approved the twelve articles through a joint resolution on September 25, 1789, and sent the articles to the states for ratification. Articles 3-12 were ratified by the required number of states on December 15, 1791. After initially failing to ratify the amendments during its 1789 legislative session, Virginia ratified Article 1 on November 3, 1791, and Articles 2-12 on December 15, 1791.

With Virginia’s ratification of Amendments 3-12, they became the first ten amendments to the United States Constitution, thereafter known as the Bill of Rights. Virginia was the eleventh state to ratify them, reaching the three-fourths threshold (since Vermont had become the 14th state in March 1791) required by Article V of the Constitution. Virginia had the distinction of being the final necessary state to approve the Bill of Rights.

Edmund Pendleton (1721-1803) was born in Caroline County, Virginia. He served an apprenticeship with a local court clerk and was licensed to practice law in 1741 and was admitted to the bar of the General Court in 1745. He represented Caroline County in the House of Burgesses from 1752 to 1776. He served as a delegate to the First Continental Congress, President of the Virginia Committee of Safety (de facto governor, 1775-1776), and President of the Virginia Convention, instructing delegates to the Second Continental Congress to vote in favor of independence. Pendleton then served as Speaker of Virginia’s new House of Delegates and worked with Thomas Jefferson and George Wythe on the revision of Virginia’s legal code. In 1778, Pendleton was appointed the first president of Virginia’s Supreme Court of Appeals and held that position until his death. He also presided over Virginia’s 1788 Convention that ratified the U.S. Constitution.

John James Beckley (1757-1807) was born in London and sent by his parents to Virginia as an indentured servant at the age of 11, and sold to the mercantile firm of John Norton & Son. Through John Clayton, he met many influential citizens of the colony. Although not a student at the College of William and Mary, the Phi Beta Kappa Society, which began there in 1776, broadened its requirements in 1778, and Beckley was elected to membership a few months later. He served as mayor of Richmond from 1783 to 1784 and from 1788 to 1789. In the latter year, under James Madison’s sponsorship, he became the clerk of the U.S. House of Representatives. He served until 1797 and again from 1801 to 1807. By 1792, he had begun a propaganda machine for the nascent Republican party and that year brought to light Alexander Hamilton’s relationship with Maria and James Reynolds. Confronted by James Monroe, Hamilton admitted to the affair but denied financial wrongdoing, and the Republicans kept the matter confidential until 1797. In 1796, Beckley managed Thomas Jefferson’s presidential campaign in Pennsylvania. More active in promoting Jefferson in 1800, he became the first American professional campaign manager. President Jefferson appointed him as the first Librarian of Congress in 1802, a position Beckley held until his death.

Census:

1. This copy, originally sent to Thomas Collins of Delaware.

2. Copy sent to the Governor of Massachusetts, Document 851, Legislative Papers, Senate Files, Massachusetts Archives, Boston, MA. Reproduced in John Kaminski et al., eds., The Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution: Ratification of the Constitution by the States: Virginia. Supplemental Documents, Part 2 (2019), 868-882.

3. Copy in the Helen Marie Taylor Trust, currently on loan to the Virginia Museum of History and Culture in Richmond, Virginia.

Sales History:

Helen Marie Taylor copy:

1979/06/20 Sotheby Parke Bernet (Sang Collection), lot 843

1989/05/17 Christie's (Middendorf Collection), lot 312

The present copy:

1945/05/08 Parke Bernet Galleries, Inc. (“Autograph Letters Manuscripts and Rare Books. Collected by the Late John Gribbel, Philadelphia. Part Four.”), lot 410. Originally with cover letter to Thomas Collins of Delaware. Other items sent to Collins were sold in the early 20th c at Henkels.

1989 (after 05/17) Joseph Rubinfine to David Karpeles, private sale.

2022/07/21 Sotheby’s, lot 1005.

Complete Transcript, following page and line breaks of the manuscript.

Virginia towit:

In Convention,

Wednesday, the 25th of June 1788.

The Convention, according to the order of the day, resolved

itself into a Committee of the whole Convention, to take into farther conside-

ration the proposed Constitution of Government for the United States; and

after some time spent therein, Mr President resumed the Chair, and

Mr [Thomas]Mathews reported, that the Committee had, according to order, again

had the said proposed Constitution under their consideration and had gone

through the same, and come to several Resolutions thereupon, which he read

in his place and afterwards delivered in at the Clerk’s table, where the same

were again read and are as followeth;

Whereas the powers granted under the proposed Constitution are the

gift of the people, and every power granted thereby remains with them, and at

their will; no right, therefore, of any denomination can be cancelled, abridged,

restrained or modified by the Congress, by the Senate or House of Represen-

tatives, acting in any capacity, by the President, or any Department or Officer

of the United States, except in those instances in which power is given by

the Constitution for these purposes: And among other essential Rights, liberty

of Conscience and of the Press cannot be cancelled, abridged, restrained or

modified, by any authority of the United States;

And, Whereas any Imperfections which may exist in the said

Constitution ought rather to be examined in the mode prescribed therein

for obtaining Amendments, than by a delay with a hope of obtaining

2

previous amendments, to bring the Union into danger;

Resolved, that it is the opinion of this Committee, that

the said Constitution be ratified.

But in order to relieve the apprehensions of those who may be

solicitous for Amendments,

Resolved, that it is the opinion of this Committee, that

whatsoever Amendments may be deemed necessary be recommended to the

consideration of the Congress which shall first assemble under the said

Constitution, to be acted upon according to the mode prescribed in the

fifth Article thereof.

The first Resolution being read a second time, a motion was

made, and the question being put to amend the same, by substituting in

lieu of the said Resolution and it’s preamble, the following Resolution;

Resolved, that previous to the ratification of the new Constitution

of Government recommended by the late Fœderal Convention, a Declara-

tion of Rights asserting and securing from encroachment the great princi-

ples of Civil and Religious Liberty, and the unalienable rights of the people,

together with amendments to the most exceptionable parts of the said Consti-

tution of Government, ought to be referred by this Convention to the

other States in the American Confederacy for their consideration;

It passed in the negative Ayes 80 }

Noes 88 }

And then the main question being put, that the Convention

do agree with the Committee in the said first Resolution;

It was resolved in the affirmative Ayes 89 }

Noes 79 }

The second Resolution being then read a second time, a

motion was made and the question being put to amend the same by

striking out the preamble thereto.

It was resolved in the affirmative

[3]

And then the main question being put that the Convention do agree

with the Committee in the second Resolution so amended;

It was resolved in the Affirmative.

On motion, Ordered, that a Committee be appointed to

prepare and report such Amendments as shall by them be deemed necessary

to be recommended pursuant to the second Resolution; and that

the Honorable George Wythe, Mr Harrison, Mr Matthews, Mr Henry

His Excellency Governor Randolph, Mr George Mason, Mr Nicholas,

Mr Grayson, Mr Madison, Mr Tyler, Mr John Marshall. Mr

Monroe, Mr Ronald, Mr Bland, Mr Meriwether Smith, The

Honorable Paul Carrington, Mr Innes, Mr Hopkins, The Honorable

John Blair, and Mr Simms, compose the said Committee.

His Excellency Governor Randolph reported from the Committee

appointed according to order, a form of Ratification, which was read

and agreed to by the Convention, in the words following,

Virginia, towit:

[Avalon transcript takes up here:]

We the Delegates of the People of Virginia

duly elected in pursuance of a recommendation from the General Assembly,

and now met in Convention, having fully and freely investigated and

discussed the proceedings of the Federal Convention, and being

prepared as well as the most mature deliberation hath enabled us, to

decide thereon, Do in the name and in behalf of the

People of Virginia, declare and make known that the

4

powers granted under the Constitution, being derived from the People of the

United States may be resumed by them whensoever the same shall be

perverted to their injury or oppression, and that every power not granted

thereby remains with them and at their will: that therefore no right of

any denomination can be cancelled, abridged, restrained or modified, by

the Congress, by the Senate or House of Representatives acting in any

capacity, by the President or any department or officer of the United

States, except in those instances in which, power is given by the Constitution

for those purposes: And that among other essential rights, the liberty of

Conscience and of the press cannot be cancelled, abridged, restrained or

modified by any authority of the United States.

With these impressions with a solemn appeal to the Searcher

of hearts for the purity of our intentions, and under the conviction,

that whatsoever imperfections may exist in the Constitution, ought

rather to be examined in the mode prescribed therein than to

bring the Union into danger by a delay, with a hope of obtaining

Amendments previous to the Ratification,

We the said Delegates, in the name and in

behalf of the People of Virginia, Do by these pre-

sents assent to and ratify the Constitution recommend-

ed on the seventeenth day of September, one thousand seven hundred and

eighty seven by the Fœderal Convention for the Government of the

United States; hereby announcing to all those whom it

may concern, that the said Constitution is binding upon the

said People, according to an authentic Copy hereto annexed.

(Here follows the Constitution.)

[5]

In Convention

Friday,the 27th of June 1788.

Mr Wythe reported from the committee appointed, such Amendments

to the proposed Constitution of Government for the United States as

were by them deemed necessary to be recommended to the consideration of

the Congress which shall first assemble under the said Constitution,

to be acted upon according to the mode prescribed in the fifth Article

thereof; and he read the same in his place, and afterwards delivered

them in at the Clerk’s table, where the same were again read, and

are as followeth:

That there be a Declaration or Bill of Rights asserting and

securing from encroachment the essential and unalienable rights of the people

in some such manner as the following;

First, That there are certain natural rights of which men, when

they form a social compact, cannot deprive or divest their posterity, among

which are the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring,

possessing and protecting property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness

and safety.

Second, That all power is naturally vested in, and consequently

derived from, the people; that magistrates, therefore, are their Trustees

and Agents, and at all times amenable to them.

Third, That Government ought to be instituted for the common

benefit, protection and security of the people, and that the doctrine

of Non-resistance against arbitrary power and oppression, is absurd,

slavish, and destructive of the good and happiness of mankind.

Fourth, That no man or set of men are entitled to exclusive or

6

separate public emoluments or privileges from the Community, but in

consideration of public services; which not being descendible, neither ought

the offices of Magistrate, Legislator or Judge, or any other public

Office to be hereditary.

Fifth, That the legislative, executive, and judiciary powers of

Government should be separate and distinct, and that the Members of the

two first may be restrained from oppression by feeling and participating

the public burthens, they should, at fixed periods be reduced to a private

station, return into the mass of the people, and the vacancies be supplied

by certain and regular elections; in which all or any part of the former

Members to be eligible or ineligible, as the rules of the Constitution of

Government, and the Laws shall direct.

Sixth, That Elections of representatives in the legislature ought to

be free and frequent, and all men having sufficient evidence of permanent

common interest with and Attachment to the Community, ought to have the

right of Suffrage: and no aid, charge, tax or fee can be set, rated or levied

upon the people without their own consent, or that of their representatives

so elected, nor can they be bound by any Law, to which they have not in

like manner assented for the public good.

Seventh, That all power of suspending Laws, or the execution of

laws by any authority without the consent of the Representatives of the

People in the Legislature, is injurious to their rights and ought not to be

exercised.

Eighth, That in all capital and criminal prosecutions, a man

hath a right to demand the cause and nature of his accusation, to be

confronted with with the accusers and witnesses, to call for evidence

and be allowed counsel in his favor, and to a fair and speedy trial

by an impartial Jury of his vicinage, without whose unanimous consent

[7]

he cannot be found guilty (except in the government of the land and

naval forces) nor can he be compelled to give evidence against himself.[4]

Ninth, That no freeman ought to be taken, imprisoned, or

disseised of his freehold, liberties, privileges or franchises, or outlawed or

exiled, or in any manner destroyed or deprived of his life, liberty or

property but by the law of the land.

Tenth, That every freeman restrained of his liberty is entitled

to a remedy to enquire into the lawfulness thereof, and to remove the

same, if unlawful, and that such remedy ought not to be denied nor

delayed.

Eleventh, That in controversies respecting property, and in suits

between man and man, the ancient trial by jury is one of the greatest

securities to the rights of the people, and ought to remain sacred and

inviolable.[5]

Twelfth, That every freeman ought to find a certain remedy

by recourse to the laws for all injuries and wrongs he may receive in

his person, property or character. He ought to obtain right and justice

freely without sale, completely and without denial, promptly and without

delay, and that all establishments or regulations contravening these rights,

are oppressive and unjust.

Thirteenth, That excessive Bail ought not be required nor

excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.[6]

Fourteenth, That every freeman has a right to be secure from

all unreasonable searches, and siezures of his person, his papers and

property; all warrants, therefore, to search suspected places, or sieze any

freeman, his papers or property without information upon oath (or affirma-

tion of a person religiously scrupulous of taking an oath) of legal and

sufficient cause, are grievous and oppressive; and all general warrants to

8

search suspected places, or to apprehend any suspected person without

specially naming or describing the place or person are dangerous and ought

not to be granted.[7]

Fifteenth, That the people have a right peaceably to assemble

together to consult for the common good, or to instruct their representa-

tives; and that every freeman has a right to petition or apply to the

legislature for redress of grievances.[8]

Sixteenth, That the people have a right to freedom of speech,

and of writing and publishing their sentiments; but the freedom of

the press is one of the greatest bulwarks of liberty and ought not to be

violated.[9]

Seventeenth, That the people have a right to keep and bear

arms; that a well regulated militia composed of the body of the people

trained to arms, is the proper, natural and safe defence of a free State.[10]

That standing armies in time of peace are dangerous to liberty, and

therefore ought to be avoided, as far as the circumstances and protection of the

Community will admit; and that in all cases the military should be

under strict subordination to and governed by the civil power.

Eighteenth, That no soldier in time of peace ought to be quartered in

any house without the consent of the Owner, and in time of war in such manner only

as the laws direct.[11]

Nineteenth, That any person religiously scrupulous of bearing arms ought

to be exempted upon payment of an equivalent to employ another to bear arms in his

stead.[12]

Twentieth, That religion, or the duty which we owe to our Creator,

and the manner of discharging it, can be directed only by reason and conviction,

not by force or violence, and therefore all men have an equal, natural and unaliena-

ble right to the free exercise of religion according to the dictates of conscience, and

that no particular religious sect or society ought to be favored or established by

law in preference to others.[13]

[9]

Amendmentsto the Constitution

First, That each State in the Union shall respectively retain every

power, jurisdiction and right, which is not by this Constitution delegated to

the Congress of the United States, or to the departments of the Fœderal

Government.

Second, That there shall be one Representative for every thirty

thousand, according to the enumeration or census mentioned in the Constitution,

until the whole number of representatives amounts to two hundred; after which

that number shall be continued or encreased as Congress shall direct,

upon the principles fixed in the Constitution, by apportioning the representatives

of each State to some greater number of people from time to time as popula-

tion encreases.[14]

Third, When Congress shall lay direct taxes or excises, they shall

immediately inform the Executive power of each State, of the quota of such

State according to the census herein directed, which is proposed to be thereby

raised; and if the legislature of any State shall pass a law which shall

be effectual for raising such Quota at the time required by Congress, the

taxes and excises laid by Congress shall not be collected in such State.

Fourth, That the members of the Senate and House of Representatives

shall be ineligible to, and incapable of holding, any civil office under the

authority of the United States, during the time for which they shall respectively

be elected.

Fifth, That the Journals of the proceedings of the Senate and House of

Representatives shall be published at least once in every year, except such parts

thereof relating to Treaties, Alliances, or military operations, as in their judgment

require secrecy.

Sixth, That a regular statement and account of the receipts and

10

expenditures of all public money shall be published at least once in every

year.

Seventh, That no commercial treaty shall be ratified without the

concurrence of two-thirds of the whole number of the members of the Senate; and

no treaty ceding, contracting, restraining or suspending the territorial rights or

claims of the United States, or any of them, or their, or any of their rights or

claims to fishing in the American Seas, or navigating the American rivers,

shall be made, but in cases of the most urgent and extreme necessity; nor

shall any such treaty be ratified without the concurrence of three-fourths

of the whole number of the members of both houses respectively.

Eighth, That no navigation-law, or law regulating Commerce,

shall be passed without the consent of two-thirds of the members present in

both houses.

Ninth, That no standing army or regular troops shall be raised,

or kept up in time of peace, without the consent of two-thirds of the

members present, in both houses.

Tenth, That no soldier shall be inlisted for any longer term

than four years, except in time of war, and then for no longer term than

the continuance of the war.

Eleventh, That each State respectively shall have the power

to provide for organizing, arming and disciplining it’s own militia, whensoever

Congress shall omit or neglect to provide for the same. That the militia shall

not be subject to martial law, except when in actual service in time of war,

invasion or rebellion, and when not in the actual service of the United States,

shall be subject only to such fines, penalties and punishments as shall be directed

or inflicted by the laws of it’s own State.

Twelfth, That the exclusive power of legislation given to Congress

over the Fœderal Town and it’s adjacent District, and other places purchased

11

or to be purchased by Congress of any of the States, shall extend only to

such regulations as respect the police and good government thereof.

Thirteenth, That no person shall be capable of being President of the

United States for more than eight years in any term of sixteen years.[15]

Fourteenth That the Judicial power of the United States shall be

vested in one Supreme Court, and in such Courts of Admiralty as Congress may

from time to time ordain and establish in any of the different States: The

Judicial power shall extend to all cases in law and equity arising under

Treaties made or which shall be made under the authority of the United States;

to all cases affecting ambassadors, other foreign ministers and consuls; to all cases

of Admiralty and maritime jurisdiction; to controversies to which the United

States shall be a party; to controversies between two or more States, and between

parties claiming lands under the grants of different states. In all cases affecting

ambassadors, other foreign ministers and consuls, and those in which a state shall

be a party, the Supreme Court shall have original jurisdiction; in all other

cases before mentioned, the Supreme Court shall have appellate Jurisdiction, as to

matters of law only; except in cases of equity and of admiralty and maritime

jurisdiction, in which the Supreme Court shall have appellate Jurisdiction

both as to law and fact, with such exceptions and under such regulations

as the Congress shall make: But the judicial power of the United States

shall extend to no case where the cause of Action shall have originated

before the ratification of this Constitution; except in disputes between States

about their Territory; disputes between persons claiming lands under the

grants of different States, and suits for debts due to the United States.

Fifteenth, That in criminal prosecutions, no man shall be restrained

in the exercise of the usual and accustomed right of challenging or excepting to

the Jury.

Sixteenth, That Congress shall not alter, modify, or interfere in the

12

times, places, or manner of holding elections for Senators and Representatives,

or either of them, except when the legislature of any State shall neglect, refuse,

or be disabled by invasion or rebellion to prescribe the same.

Seventeenth, That those clauses, which declare that Congress shall

not exercise certain powers, be not interpreted in any manner whatsoever

to extend the powers of Congress; but that they may be construed either as making

exceptions to the specified powers where this shall be the case, or otherwise,

as inserted merely for greater caution.

Eighteenth, That the laws ascertaining the compensation to Senators

and Representatives for their Services, be postponed in their operation until

after the election of Representatives immediately succeeding the passing thereof;

that excepted, which shall first be passed on the subject.[16]

Nineteenth, That some Tribunal other than the Senate

be provided for trying impeachments of Senators.

Twentieth, That the Salary of a Judge shall not be encreased

or diminished during his continuance in office, otherwise than by general

regulations of Salary which may take place on a revision of the Subject

at stated periods of not less than seven years, to commence from the

time such Salaries shall be first ascertained by Congress.

And the Convention do, in the name and behalf of

the People of this Commonwealth enjoin it upon their Repre-

sentatives in Congress, to exert all their influence and use all

reasonable and legal methods to obtain a Ratification of the

foregoing alterations and provisions in the manner provided by

the fifth Article of the said Constitution; and in all Congres-

sional laws to be passed in the mean time, to conform to the spirit of

these Amendments as far as the said Constitution will admit.

And so much of said amendments as is contained in the

[13]

first twenty Articles constituting the Bill of Rights being again read:

Resolved, that this Convention do concur therein.

The other Amendments to the said proposed Constitution, contained

in twenty one[17] Articles being then again read, a motion was made, and the

question being put to amend the same by striking out the third Article

containing these words:

“When Congress shall lay any direct taxes or excises, they shall

immediately inform the Executive power of each State, of the quota of such

State according to the census herein directed, which is proposed to be thereby

raised; and if the Legislature of any State shall pass a Law which shall

be effectual for raising such quota at the time required by Congress,

the Taxes and Excises laid by Congress shall not be collected in such

State.”

It passed in the Negative Ayes 65 }

Noes 85 }

And then, the main question being put that this Convention

do concur with the Committee in the said Amendments;

It was resolved in the Affirmative.

Edmd Pendleton President

Attest,

John Beckley, Secretary.

[14]

[Docketing:]

Proceedings of the Convention

of Virginia.

June 25, 1788.

[1] John P. Kaminski et al., eds., The Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution, Volume X: Ratification of the Constitution by the States: Virginia (3) (Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1993), 1474, 1479.

[4] The Fifth Amendment prohibits double jeopardy and testifying against oneself. The Sixth Amendment provides for “a speedy and public trial” in criminal prosecutions and protects the defendant’s ability to confront accusers and to have legal counsel.

[5] The Seventh Amendment protects the right of “trial by jury” in common law suits.

[6] The Eighth Amendment protects against “excessive bail”; “excessive fines”; and “cruel and unusual punishments.”

[7] The Fourth Amendment protects against “unreasonable searches and seizures.”

[8] The First Amendment protects the right of the people “peaceably to assemble” and to “petition” the Government for a “redress of grievances.”

[9] The First Amendment protects “freedom of speech” and “of the press.”

[10] The Second Amendment protects the right to “keep and bear Arms” and “a well regulated Militia.”

[11] The Third Amendment prohibits the quartering of soldiers in private homes in times of peace.

[12] The protection of those “religiously scrupulous of bearing arms” was in the Fifth Article approved by the House of Representatives on August 24, 1789, but it was absent in the versions approved by the Senate and full Congress and ratified by the states as the Second Amendment.

[13] The First Amendment protects the “free exercise” of religion.

[14] Congress approved a form of this amendment as the First Article and sent it to the states for ratification, but it fell one state short of ratification. When originally submitted, ratification by 9 states would have met the requirement, but by the time both Virginia and Vermont ratified it on November 3, 1791, the requisite number had risen to 11. When in June 1792, Kentucky became the 11th state to ratify it, the requisite number had risen to 12.

[15] The Twenty-second Amendment, ratified in 1951, prohibited any person from being elected to the office of the President more than twice.

[16] The Second Article that Congress proposed to the states read, “No law, varying the compensation for the services of the Senators and Representatives, shall take effect, until an election of Representatives shall have intervened.” Only six of the original thirteen states ratified the amendment. In the 1980s, a University of Texas undergraduate student began a letter-writing campaign to get additional states to ratify the amendment. By May 1992, the required 39 states had ratified the proposed amendment, and it became the Twenty-seventh Amendment to the Constitution; seven additional states subsequently ratified the amendment.

[17] The paragraph beginning “And the Convention do, in the name and behalf of the People of this Commonwealth enjoin it upon their Representatives in Congress…” may have been considered a twenty-first article.