Click to enlarge:

Select an image:

Dr. Lewis Leprilete was one of the few French persons admitted to United States citizenship under the provisions of the first Naturalization Act of 1790. He became the first to advertise cataract extraction in the United States, and the first American author to publicize Benjamin Franklin’s bifocals. Leprilete returned to France, and was forced to serve in the French army in Guadaloupe. He was able to come back to the United States in 1801.

[IMMIGRATION].

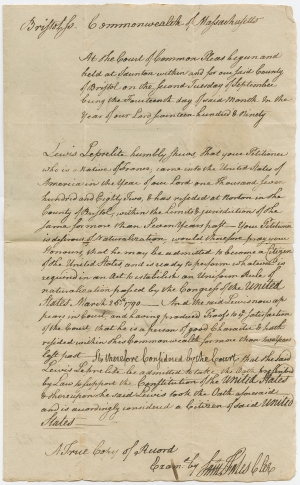

Manuscript Document Signed. Taunton, Bristol County, Massachusetts, Court of Common Pleas, begun and held September 14, 1790. Naturalization Certificate for Dr. Lewis Leprilete. A true copy, penned and signed by Samuel Fales, [between September 14, 1790 and March 19, 1795]. With certification on verso signed by notary public Samuel Cooper, Boston, March 19, 1795, and bearing Cooper’s official embossed paper wafer seal. 2 pp., 7⅝ x 12½ in.

Inventory #25787

Price: $9,500

As published in Acts and Laws, Passed by the General Court of Massachusetts, March 6, 1790, 19 individuals, including Leprilete, had petitioned the state to become citizens. The first Federal Naturalization Act of March 26, 1790 soon followed. Arguably this group of Massachusetts citizens are among the first naturalized by the Federal authority. Possibly the only document from that group extant.

White persons living in the thirteen colonies on July 4, 1776, became citizens of their states by virtue of their residence in the rebelling colonies. The Articles of Confederation implied that citizens of one state had rights in other states as well, and Article IV of the United States Constitution, ratified in June 1788, created a national citizenship, but it remained vaguely defined until after the Civil War.[1]

In the eighteenth century, the primary reasons for an alien to become a citizen were to acquire the right to vote and the ability to hold property outright and pass it on to heirs.[2] Aliens did not need to become a citizen to buy or sell property, hold a job, or get married. Many immigrants lived most of their lives in the United States and did not complete or even begin the process of naturalization. Because most states had property requirements for voting, many immigrants could not vote even if they were naturalized because they did not own enough property.

Excerpts:

“Lewis Leprelite humbly shews, That your Petitioner who is a native of France, came into the United States of America in the Year of our Lord one Thousand seven hundred and Eighty Two, & has resided at Norton in the County of Bristol, within the Limits & jurisdiction of the same for more than Seven Years past. Your Petition is desirous of Naturalization, would therefore pray your Honours, that he may be admitted to become a Citizen of the United States, and is ready to perform whatever is required in an Act to establish an Uniform Rule of naturalization passed by the Congress of the United States March 26th 1790. And the said Lewis now appears in Court, and having produc’d Proofs to ye Satisfaction of the Court, that he is a person of good Character & hath resided in this Commonwealth for more than two Years last past. It is therefore Considered by the Court that the said Lewis Leprelite be admitted to take the Oath prescribed by Law to support the Constitution of the United States & thereupon the said Lewis took the oath aforesaid, and is accordingly considered a Citizen of said United States.”

“A True Copy of Record

“Examd by Saml: Fales Clek”

“I Samuel Cooper Notary Public duly admitted & sworn & dwelling in Boston aforesaid, do Certify to all whom it may concern that Samuel Fales is Clerk of the Court of Common Pleas for the County of Bristol in the Commonwealth aforesaid....

“Saml Cooper Not. Pub”

Historical Background

The framers of the Declaration of Independence included among their list of grievances that the King had prevented the peopling of the United States by obstructing “the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners” and by refusing to pass laws to encourage immigration. The Constitutional Convention empowered Congress under the new government to “establish an uniform rule of Naturalization.”

With the end of the Revolutionary War, individual states established a variety of naturalization policies. Many of the middle and southern states defined the rights of naturalization in new state constitutions or by statute. New England states relied on private legislation and did not adopt general or public laws of naturalization. The reciprocity built into the Articles of Confederation, ratified in 1781, created a sort of de facto national citizenship that laid the foundation for a national constitutional standard for naturalization.

The Constitution gave Congress the right to determine the process by which the foreign-born could obtain U.S. citizenship. On March 26, 1790, Congress passed An Act to Establish an Uniform Rule of Naturalization. Any free white person of good character who had lived for at least two years in the United States and for at least one year in the state of residence could file a Petition for Naturalization. If “any common law court of record” in his or her place of residence were convinced of the applicant’s “good character,” it could administer an oath of allegiance to support the Constitution of the United States and declare the person a citizen of the United States. The residency requirements were largely to avoid the anti-republican threat of absentee landowners in favor of actual settlers.

The legislation did not allow people of color, or indentured servants or women (considered dependents, thus incapable of casting their own vote) to gain citizenship. Step by step, over the next century and a half, those restrictions were eliminated, while other changes were made.

Demographers estimate that approximately 57,800 people immigrated to the United States between 1783 and 1789, only 200 of whom were from France. Approximately 3,900,000 people lived in the United States in 1790, roughly 950,000 of whom were immigrants.[3] Of those, 360,000 from Africa and were ineligible for citizenship. At least 425,500 were from the British Isles, while 103,000 were from German states. Only 3,000 were from France, primarily Huguenots.[4] From 1790 to 1799, immigration estimates suggest that nearly 98,000 people immigrated to the United States. Nearly 80 percent came from the United Kingdom, and approximately 1,700 came from France.[5]

In 1795, Congress replaced the first act with a two-step process that required prospective citizens to be in residence for five years and to declare their intention to become a citizen at least three years prior to their formal application. In a period of intense nationalism during the quasi-war with France, Congress in 1798 extended the residency requirement again, this time to 14 years, with a notice of intention 5 years earlier. This act was one of the four Alien and Sedition Acts, which the Federalist majority passed against the perceived threats posed by foreigners, especially French revolutionaries, but also Irish and other immigrants. The unpopularity of these acts led to Democratic-Republican victories in the 1800 presidential and congressional elections. In 1802, a Democratic-Republican majority in Congress returned the residency requirement to five years, where it remained for much of the nineteenth century.

After ratification of the 14th Amendment (Equal Protection), the Naturalization Act of 1870 extended the naturalization process to “aliens of African nativity and to persons of African descent.” The 14th Amendment also made more explicit the principle of “birthright citizenship,” through which an individual acquires citizenship in the United States by virtue of being born in the United States or its territories, though it did not apply to Native Americans until 1924.

Naturalization remained unavailable to Asian immigrants. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 prohibited all immigration of Chinese laborers and was made permanent in 1902. The Magnuson Act of December 1943 allowed limited Chinese immigration and permitted Chinese nationals for the first time to become naturalized citizens. In 1946, Congress passed an act giving individuals from India and the Philippines access to the naturalization process.

Naturalization regulations affecting women evolved differently. An 1855 act allowed immigrant women to acquire citizenship through marriage to an American citizen or when their husband became a naturalized citizen. Further tying a woman’s citizenship to that of her husband, a 1907 law stipulated that American women who married aliens would lose their American citizenship. Not until Congress passed the Cable Act in 1922 could immigrant women acquire citizenship in their own right.

Lewis Leprilete/Leprelite (1750-1804) was born in Nantes, France, became a physician, and immigrated to the United States in 1782. That year, in Providence, Rhode Island, he was the first to advertise cataract extraction in the United States. When he came to Norton, Massachusetts, around the end of the Revolutionary War, the widow Deborah Hodges Allen (1748-1824) bought him the first horse and saddle he owned in America. They married in March 1784, and had one son who died of smallpox as a child. Several of Leprilete’s medical students named their sons after him. In 1791, he moved to Jamaica Plain in Boston, where he was the first American author to publicize Benjamin Franklin’s invention of the bifocals. After his only son died in November 1792, Leprilete returned to France. He was forced to serve in the French army and sent to Guadeloupe as surgeon for an infantry brigade by 1799. He spent several years in Guadeloupe, before returning to the United States in July 1801. He lived in Franklin, Massachusetts, until his death on July 29, 1804. In his will, signed July 4, 1804, Leprilete provided for his wife and for his “adopted son” and student Dr. Nathaniel Miller (1771-1850), who was also the executor of his will. Leprilete gave his body to Dr. John Warren (1753-1815) of Boston for anatomical purposes; it was removed from the grave after the funeral services.

Samuel Fales (1750-1818) was born in Bristol, Rhode Island, and graduated from Harvard College in 1773. Three years later, he received an M.A. degree from Harvard. He became a lawyer and settled in Taunton, Massachusetts. From 1774 to 1804, he served as clerk of the Inferior Court of Common Pleas and the Court of Sessions of Bristol County, Massachusetts. From 1776 to 1779, he was a captain in the Revolutionary War. In 1781, Fales married Sarah Cook in Tiverton, Rhode Island; they had fifteen children, of whom several died young. From 1805 to 1811, Fales served as Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas for Bristol County, and from 1813 to 1817, as a Councillor of Massachusetts, a member of the body that advises the governor.

Provenance

By descent in the family of Leprilete’s protégé, Dr. Nathaniel Miller.

Condition

Fine

[1] In the first Congressional election cycle, American voters sent nine “naturalized” citizens to the Senate and House of Representatives; four of them had signed the new U.S. Constitution, and one, Robert Morris, had also signed the Declaration of Independence. They were “naturalized” in the sense that they had been born outside of what became the United States and had immigrated to the American colonies before the Revolutionary War.

[2] James E. Pfander and Theresa R. Wardon, “Reclaiming the Immigration Constitution of the Early Republic: Prospectivity, Uniformity, and Transparency,” Virginia Law Review 96 (March 2010): 366.

[3] The total population of 3,900,000 included fewer than 100,000 Native Americans inside territorial U.S. boundaries.

[4] The remaining 58,500 largely came from European countries, and many of these may have been from the British Isles, but the loss of records makes more precise figures difficult.

[5] Hans-Jürgen Grabbe, “European Immigration to the United States in the Early National Period, 1783-1820,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 133 (June 1989): 194.

French figures do not include temporary émigrés who returned to their homeland after a temporary stay in the United States. The 1790s also witnessed French emigration from violence in Saint Domingue, swelling immigration from the Caribbean to 12,800 in that decade.