Click to enlarge:

Select an image:

A list of stockholders, entirely in Lincoln’s hand, filed as evidence in his first significant railroad case. Lincoln’s own appearance in the shareholder list represents only the second known instance of a stock purchase by the future president. The Illinois Supreme Court’s ultimate ruling in favor of Lincoln and the railroad set an important legal precedent, upholding the binding nature of a stockholder’s contractual and financial obligations. “The decision, subsequently cited in twenty-five other cases throughout the United States, helped establish the principle that corporation charters could be altered in the public interest, and it established Lincoln as one of the most prominent and successful Illinois practitioners of railroad law” (Donald, p.155).

ABRAHAM LINCOLN.

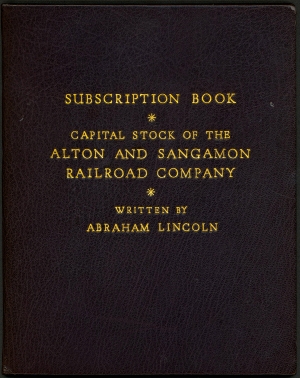

Autograph Manuscript Signed by Lincoln in text, constituting his official transcript of the “

Subscription Book of the Capital Stock of the Alton and Sangamon Rail Road Company,” incorporated February 27, 1847, transcribed in early 1851. Comprising a cover sheet titled in Lincoln’s hand, the joint stock subscription statement and list of 91 shareholders with the number of shares subscribed, and leaf with Lincoln’s legal docket: “

Alton and Sangamon Railroad Company vs. James A. Barret. Copy of contents of subscription book....” 8 pp., 6⅝ x 8¼ x ¼ in.

Inventory #27561

Price: $198,000

Historical Background

The Alton and Sangamon Rail Road Company was chartered in 1847 to construct a line from Alton, via New Berlin, to Springfield. In 1850, however, the Illinois General Assembly approved a more direct route, bypassing the landholdings of some investors. Claiming breach of contract, James A. Barret refused to make further installment payments for his 30 shares of stock, as did several others who no longer stood to benefit from the new line. In 1851, Lincoln was hired to compel the defaulting shareholders to pay the balance of their promised investment.

The tactical details are spelled out in a February 19, 1851 letter from Lincoln to William Martin, a commissioner for the sale of the company’s stock. Four suits were to be brought against stockholders who had subscribed to the initial offering, but had then failed to make the additional installment payments. In preparation, Lincoln listed the essential documents he would need in order to win a judgment. “We must prove,” he advised Martin, “that the defendant is a Stockholder,” “that the calls have been made,” and “that due notice of the calls has been given.” To show that the defendants were in fact stockholders, Lincoln explained, he needed to produce “the subscription book with the defendant’s name, and proof of the genuineness of the signature, together with any competent parole or evidence, that he made the advance payment” (Basler 2:99).

Lincoln’s meticulous transcript of the subscription book was a key piece of the evidence filed in Sangamon Circuit Court on February 22, 1851. The book includes Barret’s name, and the subscription statement (transcribed by Lincoln on page two) is explicit about the shareholders’ obligations.

We the subscribers to the Capital Stock of the Alton and Sangamon Rail Road Company...do hereby agree...to pay the balance of the installments due on said stock by us subscribed, when the same may be called for by the board of Directors of said Company when duly organized in conformity with the Charter approved February 27th 1847.

“A. Lincoln,” with six shares for $600, is prominent among the 91 subscriber names. (The only other known record of a Lincoln stock purchase dates from 1836, when he bought one share in the Beardstown and Sangamon Canal.)

In June of 1847, as head of a committee to promote subscriptions for the projected railroad, Lincoln wrote an open letter to the “People of Sangamon County” appealing for their support. Railroad construction was booming, and Lincoln anticipated that a line between Springfield and Alton would prove a lucrative investment for himself and his state. “The whole is a matter of pecuniary interest,” he argued. “The proper question for us is, whether, with reference to the present and the future, and to direct and indirect results, it is our interest to subscribe. If it can be shown that it is, we hope few will refuse” (Basler, 1:396-398).

The list of subscribers is itself of considerable interest. It includes J[ohn] Hay (1775-1865, the grandfather of Lincoln’s later secretary, John Hay, 2 shares), Ninian W. Edwards (1809-1889, husband of Mary Todd Lincoln’s sister, 20 shares), John T. Stuart (1807-1885, Lincoln’s law partner, 5 shares), Henry Yates (1786-1865, father of Illinois governor Richard Yates, 10 shares), Noah W. Matheny (1815-1877, clerk of Sangamon County), and others. (In the subscription book, Henry Yates, hedging his bets, has added a condition beneath his name: “if the Road intersects the M. & S R R at New Berlin.”)

Lincoln was mindful of the critical issues raised by the Alton and Sangamon lawsuits and “took extraordinary pains to construct an airtight case for his client” (Donald, p.155). To Martin, he pointed out the legal issues, adding “I have labored hard to find the law,” in preparation for the trials. In the end, two of the defaulting stockholders paid their delinquent calls. The suits against James A. Barret and Joseph Klein came to trial in the Sangamon Circuit Court in August of 1851, with Lincoln handling both the trials and the appeals for the railroad.

Lincoln’s preparation proved its worth – the rulings were in favor of the railroad. “Illinois Supreme Court Justice Samuel H. Treat ruled that public utility superseded private profit. If Barret had won the case, other stockholders would balk at fulfilling their obligations. The rule of caveat emptor protected corporate management from stockholder’s personal interests and encouraged subsequent investment” (Lincoln Legal Briefs, Oct-Dec, 1990, no. 16, online).

At the time he transcribed this document, Lincoln was an attorney on the 8th Judicial Circuit, and also managed a thriving appellate and federal court practice. He handled a number of railroad-related cases, representing both private individuals as well as the railroads themselves. He was not, as some have argued, a hired gun for corporate interests. Rather, as his law partner William Herndon described him, Lincoln was “purely and entirely a case lawyer.”

The fact that Lincoln, despite his commitment to railroading, often handled suits against the carriers casts light on his understanding of the lawyer’s role in society…He simply could not afford to take only one side in legal disputes. Nor did Lincoln pursue some political or philosophical agenda through litigation. He was not concerned with developing a consistent legal ideology. His business, as Donald reminds us, “was law, not morality.” (James W. Ely, “Lincoln as Railroad Attorney,” Indiana Historical Society Symposium, April 15-16, 2005)

Though a prominent lawyer, Lincoln was still smarting over recent political defeats. Elected to the U.S. Congress in 1846, he had served out his term, but his outspoken opposition to the Mexican-American War had cost him any chance at a second term. He subsequently failed in his attempt to become commissioner of the General Land Office. Lincoln declined an appointment as governor of the Oregon Territory, instead returning to his law practice with William H. Herndon in Springfield, Illinois. He would not attempt a political comeback until 1854.

The rail line was ultimately highly profitable. Lincoln’s overriding belief in the broader benefits of internal improvements is best expressed in a speech he delivered before Congress in 1848.

[L]et the nation take hold of the larger works, and the states the smaller ones; and thus, working in a meeting direction, discreetly but steadily and firmly what is made unequal in one place may be equalized in another, extravagance avoided, and the whole country put on that career of prosperity which shall correspond with it’s extent of territory, it’s natural resources, and the intelligence and enterprize of it’s people.

Reference

“Barret v. Alton & Sangamon Railroad,” in Daniel W. Stowell et al., eds., The Papers of Abraham Lincoln: Legal Documents and Cases, 4 vols. (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2008), 2:172-210.