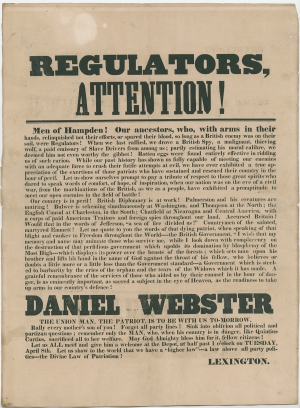

Click to enlarge:

“Daniel Webster The Union Man, the Patriot, is to be with us To-morrow… Let us all meet to give him a welcome at the Depot… Let us show to the world that we have a ‘higher law’—a law above all party politics—the Divine Law of Patriotism!”

[DANIEL WEBSTER].

Broadside announcing his upcoming arrival at Springfield, Massachusetts, April 7, [1851]. 1 p., 12 x 16½ in.

Inventory #24609

Price: $2,900

Excerpts:

“Men of Hampden! Our ancestors, who, with arms in their hands, relinquished not their efforts, or spared their blood, so long as a British enemy was on their soil were Regulators! When we last rallied, we drove a British Spy, a malignant, thieving wolf, a paid emissary of Slave Drivers from among us; partly estimating his moral caliber, we deemed him not even worthy of the gibbet! Rotten eggs were found entirely effective in ridding us of such carion. While our past history has shown us fully capable of meeting our enemies with an adequate force to crush their futile attempts at evil, we have ever exhibited a true appreciation for the exertions of those patriots who have sustained and rescued their country in the hour of peril. Let us show ourselves prompt to pay a tribute of respect to those great spirits who dared to speak words of comfort, of hope, of inspiration, when our nation was on the eve of a civil war from the machinations of the British, as we as a people, have exhibited a promptitude to meet our open enemies in the field of battle!”

“Our country is in peril! British diplomacy is at work! Palmerston and his creatures are untiring! Bulwer is scheming simultaneously at Washington, and Thompson at the North; the English Consul at Charleston, in the South; Chatfield in Nicaragua and Central America, with a corps of paid American Traitors and foreign spies throughout our land. Accursed Britain! Would that in the words of Jefferson, ‘a sea of fire divided us!’[1] Countrymen of the sainted, martyred Emmett![2] Let me quote to you the words of that dying patriot, when speaking of that blight and canker to Freedom throughout the World—the British Government, ‘I wish that my memory and name may animate those who survive me, while I look down with complacency on the destruction of that perfidious government which upolds its domination by blasphemy of the Most High...a Government which is steeled to the barbarity by the cries of the orphan and the tears of the Widows which it has made.[’] A grateful remembrance of the services of those who aided us by their counsel in the hour of danger, is as eminently important, as sacred a subject in the eye of Heaven, as the readiness to take up arms in our country’s defence!”

“Daniel Webster / The Union Man, the Patriot, is to be with us To-morrow.

“Rally every mother’s son of you! Forget all party lines! Sink into oblivion all political and partizan questions; remember only the MAN, who, when his country is in danger, like Quintius Curtius, sacrificed all to her welfare.”

“Let us all meet to give him a welcome at the Depot… Let us show to the world that we have a ‘higher law’—a law above all party politics—the Divine Law of Patriotism!”

Historical Background

In July 1850, President Millard Fillmore appointed Senator Daniel Webster of Massachusetts as Secretary of State for a second time. Webster’s support proved critical to the passage of the Compromise of 1850, which he hoped would resolve the slavery issue and preserve the national Union.

On Sunday, February 16, 1851, protestors in Springfield, Massachusetts, hung effigies of British abolitionist George Thompson (1804-1878), who was visiting on a speaking tour against the Fugitive Slave Act, and the “John Bull” characterization of Britain in a large tree on the court square. Broadsides appeared all over town anticipating Thompson’s arrival, and like this one, were signed “Lexington,” and addressed to “Regulators” and “Men of Hampden!” They characterized Thompson as a “British Spy” and “member of that very British Parliament, whose laws have placed the masses of English and Irish people in a position of such want and oppression…” The resulting riot at Hampden Hall prevented Thompson from speaking, but he delivered most of his speech nearby a day later. A local minister condemned the riot and declared that it had made Springfield “a laughing-stock…before the whole country.”[3]

Less than two months later, on April 7, 1851, the date this broadside appeared, a town meeting gathered to choose selectmen. The animosities engendered by Thompson’s visit reappeared at these spring elections. Despite Eliphalet Trask’s role as an officer at the Thompson meeting in February, he was the only candidate elected. The town could not elect two other selectmen for three more weeks, “accompanied by the most intense excitement.”

This broadside calls for Webster’s supporters to rally to welcome him home to Massachusetts. Although neither pro- nor anti-slavery, it praises Webster for his commitment to preserving the Union in the face of abolitionist complaints about the Fugitive Slave Law and perceived British meddling to encourage southerners to dissolve the Union. After Americans fought two wars against Great Britain, they displayed a recurrent fear of British interference in American politics, especially over the question of slavery. Many blamed the British both for supporting radical abolitionists with their “higher law” doctrines and for encouraging South Carolina independence to dissolve the Union. Various commentators attributed British motives for an American civil war to fear of the economic rivalry with the United States, opposition to America’s republican form of government, and a distraction from British intervention in Central America in violation of the Monroe Doctrine.

The Anti-British text accuses British Foreign Secretary and future Prime Minister Lord Palmerston; British Ambassador to the United States Henry Bulwer; abolitionist George Thompson; George Matthews (an abolitionist and British consul in Charleston, South Carolina); and Frederick Chatfield, British consul-general to the Central American republics (Guatemala, Costa Rica, Honduras, El Salvador, and Nicaragua) of endangering the United States through their scheming. Though the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty of 1850 had recently assured America that any canal across the isthmus between North and South America would remain neutral and open to all nations, many differences remained.

Webster arrived at Springfield on April 8, as he was returning to his farm in Marshfield, 100 miles east of Springfield and 30 miles southeast of Boston. People began assembling at the depot at least an hour before his arrival in the afternoon, and when he arrived, a thousand people greeted him with “cheers upon cheers.” A local newspaper described him as looking “extremely jaded and worn.” After he dined at the Massasoit House, he appeared on the balcony and gave a brief speech to the assembled crowd. Noting that he stood on Massachusetts ground, among Massachusetts men, Webster proclaimed, “I feel that I am home.” Turning to national affairs, Webster said, “The cloud that has darkened the political horizon has passed by, and what we now want, what all the great interests of the country need, is peace. We want security in the prosecution of business and of enterprise. We want...mutual confidence, mutual regard for law, and a universal disposition to consult the highest good of the whole country. It is for this end that I have labored, and shall labor.” After his brief speech, the crowd escorted Webster to the train for Boston. The newspaper characterized the event as “a quiet, respectable and wholly unorganized demonstration of respect to Mr. Webster” and “we noticed among those engaged and mingling in the demonstration, men of different parties, numbering many of the leading Democrats of this towns and of the towns around. There was nothing in the whole movement that smacked of party at all.”[4]

The Springfield Republican reprinted this broadside with the preface: “We should like to see a Fourth of July Oration by the author of the following handbill which was placarded about our streets on Tuesday morning.” The New York Herald, in a brief notice of the event, included the information that “‘Lexington’ made a call on the regulars through a handbill. The Union men were there, and such an enthusiastic assemblage never came together on such an occasion. Springfield has done her duty to the Union, and ever will.”[5]

Because of “the present excited state of the public mind, Boston’s Mayor and Board of Aldermen refused to permit Webster’s friends from using Faneuil Hall for a public reception on April 17. But the Common Council declared that action “unprecedented and injudicious” and extended their own invitation to Webster. On April 19, he replied that he could not come on his present visit, but hoped to return when the gates of Faneuil Hall were “thrown open, wide open…to let in, freely and overflowing, you and your fellow-citizens, and all men, of all parties, who are true to the Union, as well as to Liberty....”

Some of the sentiments of this broadside also fit the ethos of the nativist American Party (Know-Nothings). While Webster had twice run unsuccessfully for the Presidency, perhaps the strangest circumstance came during the election of 1852, when, without Webster’s knowledge or permission, the Know-Nothings nominated him as their candidate for the presidency. He also received the nomination of the Union Party, formed by a group of Whigs in several southern states who opposed Whig candidate Winfield Scott. Webster died nine days before the election but still received 7,000 votes, mostly in Massachusetts and Georgia.

The broadside’s final phrase is somewhat ironic. By a standard definition, patriotism favors one’s own homeland and government, rather than “Divine Law,” which is supposed to be universal. But the writer clearly takes issue with the abolitionist idea of Divine Law, which they place above even the Constitution. This author counters that by arguing that devotion to the Union is a “higher law” (different than the more abstract higher law of the crazy abolitionists). Providing a new take on the old idea of the Divine Right of Kings, this broadside’s “law of patriotism” is by extension divine, meaning higher than mere party politics.

- Text of Webster’s speech at Springfield, April 8, 1851 from Weekly National Intelligencer (Washington, DC), April 12, 1851, p8/c5.

Daniel Webster (1782-1852) was born in New Hampshire, graduated from Dartmouth College in 1801, and admitted to the bar in 1805. He represented New Hampshire in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1813 to 1817. As a preeminent attorney, he argued 223 cases before the U.S. Supreme Court, winning about half, and playing a key role in eight of the Court’s most important constitutional law cases decided between 1801 and 1824. (His arguments were accepted by Chief Justice John Marshall in Dartmouth College v. Woodward (1819), finding that a state’s grant of a business charter was a contract that the state could not impair; in McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), finding that a state could not tax a federal agency (specifically, a branch of the Bank of the United States), for the power to tax was a “power to destroy”; and in Gibbons v. Ogden (1824), finding that a state could not interfere with Congressional power to regulate interstate commerce). Webster represented Massachusetts in the House of Representatives from 1823 to 1827 and then in the Senate from 1827 to 1841 and again from 1845 to 1850. His 1830 reply to South Carolina’s Robert Y. Hayne is considered one of the greatest speeches ever delivered in the Senate. Webster’s oratorical abilities made him a powerful Whig leader, and he served as Secretary of State, first from 1841 to 1843 under Presidents William Henry Harrison and John Tyler, and again from 1850 to 1852 under President Millard Fillmore. His support of the Compromise of 1850 may have postponed a civil war, but it cost him politically in his increasingly abolitionist home state of Massachusetts.

Additional Notes

At the time, the case of Thomas Sims (1834-1902) rocked Boston. Sims had escaped from slavery in Georgia at age 17. Captured under the Fugitive Slave Act, on April 4, 1851, Sims was tried and sentenced to be returned to slavery. After efforts to rescue him failed, he was escorted by U.S. marines to a warship, where he was sent back to Georgia and sold to an owner in Mississippi. He escaped again in 1863 and returned to Boston.

[1] In 1796, Jefferson wrote to John Adams, “I am sure, from the honesty of your heart, you join me in detestation of the corruption of the English government, and that no man on earth is more incapable than yourself of seeing that copied among us, willingly. I have been among those who have feared the design to introduce it here, and it has been a strong reason with me for wishing there was an ocean of fire between that island and us.” Thomas Jefferson to John Adams, February 28, 1796.

In 1797, Jefferson wrote to Elbridge Gerry, “Much as I abhor war, and view it as the greatest scourge of mankind, and anxiously as I wish to keep out of the broils of Europe, I would yet go with my brethren into these rather than separate from them. But I hope we may still keep clear of them, notwithstanding our present thraldom, and that time may be given us to reflect on the awful crisis we have passed through, and to find some means of shielding ourselves in future from foreign influence, commercial, political, or in whatever other form it may be attempted. I can scarcely withold myself from joining in the wish of Silas Deane that there were an ocean of fire between us and the old world.” Thomas Jefferson to Elbridge Gerry, May 13, 1797. Silas Deane (1738-1789) was an American merchant, delegate to the Continental Congress, and first U.S. diplomat to France, from 1776 to 1778.

[2] Robert Emmet (1778-1803) was an Irish Republican patriot who led a rebellion against British rule in 1803. He was executed for high treason, and this quotation comes from his “Speech from the Dock” before his sentencing.

[3] Springfield Republican (MA), February 17, 1851, 2:2; Mason Arnold Green, Springfield, 1636-1886: History of Town and City (Springfield, MA: C. A. Nichols & Co., 1888), 462.

[4] Springfield Republican, April 9, 1851, 2:1. Newspapers around the country reprinted Webster’s brief speech from the Springfield Republican. See The New York Herald, April 12, 1851, 3:5; The Daily Republic (Washington, DC), April 12, 1851, 2:2; Weekly National Intelligencer (Washington, DC), April 12, 1851, 8:5; Louisville Daily Courier (KY), April 16, 1851, 2:2; The Vergennes Vermonter, April 16, 1851, 2:3; Natchez Courier (MS), April 25, 1851, 1:6; The Sun (Baltimore, MD), April 12, 1851, 1:4; and among others.

After noting the adoration of Webster by a “Scotchman,” the Springfield Republican report closed with this scene: “But there were a pair of colored girls upon the ground, who looked darkly upon the lion. ‘I wish he was dead,’ said one. ‘Oh don’t say that,’ replied the other, ‘live and let live you know.’ ‘Well I do wish he was dead,’ persisted the other. ‘Now look a’here, don’t go to going off with such wicked thoughts in your heart,’ rejoined the milder one, as they left the depot, and the subject of their conversation disappeared up the grade.”

[5] Springfield Republican, April 9, 1851, 2:4; The New York Herald, April 9, 1851, 2:4.