|

John Ericsson, inventor of the USS Monitor, discusses sales of his Caloric Engines |

Click to enlarge:

Select an image:

“I had hoped you were snugly & permanently located on the lung healing slopes of the Hudson at West Point. You will now be much nearer to the metropolis…”

JOHN ERICSSON.

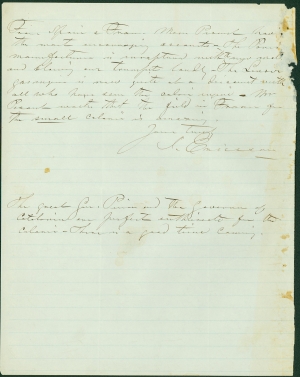

Autograph Letter Signed, to Unknown Recipient, September 29, 1860. 2 pp.

Inventory #21303.01

Price: $900

Complete Transcript

Sept. 29 / 60

My Dear Sir

Mr Mulford will send you word the moment he is ready with the [hance?]. The magnitude of the work to be done is not great, but the nature of it very troublesome as the place is very cramped under the carriage where the new [Keys?] have to be applied.

I regret to hear that you are again changing your quarters, I had hoped you were snugly & permanently located on the lung healing slopes of the Hudson at West Point. You will now be much nearer to the metropolis I think.

I have letters from Sweden, from engineer Wenstrom and am delighted to find that no trouble at all is experienced with the caloric engines which, by the way, are now being made in Germany to drawings stolen in this country My only consolation is that the engines building are the genuine Ericsson engines—no changes—it is the thing itself.

Mr. Wenstrom states that no patent in Germany would be of any use unless every state were included which is an impracticable thing. <2>

From Spain & France, Messrs Pesant have the most encouraging accounts. The Paris manufacturer is enraptured with the new [mat?] and blowing our trumpet loudly. The Lenoir gas engine is now quite at a discount with all who have seen the caloric engine. Mr Pesant writes that the field in France for the small caloric is amazing.

Yours truly / J. Ericsson

The great Gen. Prim and the Governor of Catalonia are perfect enthusiasts for the caloric. There is a good time coming.

Historical Background

By 1860, John Ericsson’s caloric engine was in widespread use in the United States and Europe. Ericsson’s engine used hot air rather than steam to drive a piston, which was safer than steam engines and required no water. It also consumed perhaps a third of the fuel of the steam engine. Hundreds of owners used Ericsson’s engine to power printing presses, hoisting gear, pumps, and mills of various sorts. Prices ranged from $200 for an 8-inch cylinder version to $6,800 for a double 48-inch cylinder.

In February 1860, the new journal Scientific American offered its assessment in response to “constant calls for our opinion of Ericsson’s air engine.” The journal concluded, “We are entirely satisfied, after a careful examination into the merits of this engine, that, for a safe, economical and convenient power for the smaller purposes of business, it is reliable.”[1] Ericsson’s chief American supporter was New York merchant John B. Kitching (1813-1887), who may have been the recipient of this letter and was an agent for the sale of the caloric engines. Another possible recipient is industrialist Cornelius H. DeLamater (1821-1889), who allowed Ericsson to experiment at his ironworks, where Ericsson’s caloric engines were manufactured.

In this letter, Ericsson expresses the difficulty of patenting his invention in Germany, which was divided into dozens of kingdoms, duchies, principalities, and independent free cities. He also notes the enthusiasm for his caloric engine in France and Spain. In August 1861, Congress recommended the construction of armored ships for the navy. Ericsson submitted a novel design with a rotating turret based on Swedish lumber rafts. The USS Monitor was constructed in approximately one hundred days, an incredible achievement, and launched on March 6, 1862. Three days later, the Monitor confronted the CSS Virginia (the former USS Merrimack) at Hampton Roads, Virginia, in the first battle between ironclad warships. Although the battle ended as a tactical stalemate, the Monitor effectively checked the Virginia’s assault on the Union fleet. Dozens of additional monitors contributed to the success of the Union Navy for the remainder of the war.

John Ericsson (1803-1889) was born in Sweden and began working independently as a surveyor at the age of fourteen. He joined the Swedish army in 1820. In his spare time, he constructed a heat engine that used fumes instead of steam as a propellant. He moved to England in 1826, but his engine that worked well with Swedish wood as fuel fared poorly with English coal. After designing an improved twin-propeller steamer, Ericsson moved to New York in 1839, and became a naturalized citizen in 1848. He continued to develop his caloric engine and naval inventions, including a torpedo, a destroyer, and a torpedo boat. (For which he won the Rumford Prize of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1862). In 1854, Ericsson presented French Emperor Napoleon III a plan for an iron-clad armored battle ship, but France did not build it. Ericsson submitted a novel design for an armored warship to the U.S. Navy, and it was built in time to confront the first Confederate ironclad.

Wilhelm Wenström (1822-1901) was a Swedish engineer. He graduated from Bergsskolan in Filipstad and also studied at the Institute of Technology in Stockholm. He worked for some time at John Ericsson’s office in New York and later became a representative of John Ericsson’s engine patent in Sweden. Joseph A. Pesant and Manuel Pesant were Spanish brothers who immigrated to New York in 1851. They operated the importing firm of Pesant Brothers in New York. Étienne Lenoir (1822-1900) was a Belgian inventor who devised the first commercially successful internal combustion engine. The Lenoir engine was a converted double-acting steam engine that used a mixture of coal-gas and air to power its two-stroke cycle engine. By 1865, more than 400 Lenoir engines were in use in France and 1,000 in Great Britain. In 1862, Lenoir built the first automobile with an internal combustion engine. General Juan Prim y Prats (1814-1870) was a Catalan Spanish general and statesman, who served briefly as Prime Minister of Spain until his assassination.

[1] “Ericsson’s Air Engine,” Scientific American (New York, NY), February 18, 1860, 121-22.