Click to enlarge:

Select an image:

“When we review the calamities which afflict so many other nations, the present condition of the United States affords much matter of consolation and satisfaction.”

A day before it is publicly issued, Secretary of State Edmund Randolph Sends Washington’s Proclamation to all American Consuls, as “a better comment upon the general prosperity of our affairs than any which I can make.” According to the President, “the present condition of the United States affords much matter of consolation and satisfaction. Our exemption hitherto from foreign war; and increasing prospect of the continuance of that exemption; the great degree of internal tranquility we have enjoyed…Deeply penetrated with this sentiment, I GEORGE WASHINGTON, President of the United States, do recommend to all Religious Societies and Denominations, and to all Persons whomsoever within the United States, to set apart and observe Thursday the nineteenth day of February next, as a Day of Public Thanksgiving and Prayer…to beseech the Kind Author of these blessings…to impart all the blessings we possess, or ask for ourselves, to the whole family of mankind.”

EDMUND RANDOLPH.

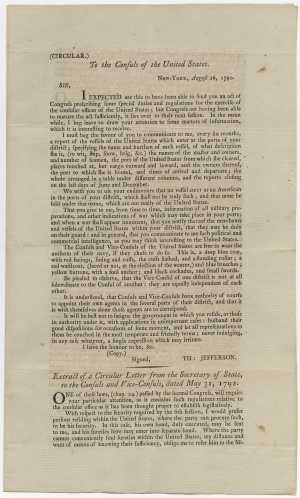

Printed Document Signed, as Secretary of State, this copy sent to Nathaniel Cutting, American Consul at Havre de Grace, France, December 31, 1794, 3 pp and blank on one integral leaf. Randolph’s circular on page one notes that he is attaching a reprint of Thomas Jefferson’s August 26, 1790 letter to our Consuls, and an extract of Jefferson’s May 31, 1792 letter calling attention to a part of the Act of Congress governing the security that consuls have to give to insure they can meet obligations they take on for the United States. He then attaches the full text of Washington’s Second Presidential Thanksgiving Proclamation, which was publicly issued a day later, on January 1, 1795. 15½ x 12⅞ in.

Inventory #24141

Price: $19,000

Historical Background

As the first Secretary of State, from 1790 to 1793, Thomas Jefferson had sent a circular to all U.S. consuls and vice-consuls around the world at the end of each session of Congress to apprise them of any new laws or other matters related to their duties. His successor, Edmund Randolph, continued the practice. Randolph sent the circular offered here to Nathaniel Cutting, U.S. consul in the port city of Havre de Grace, France. As a summary of recent events and the current state of the Union, Randolph found that President Washington’s second proclamation for a “Day of Public Thanksgiving and Prayer” was best suited to the purpose.

As Secretary of State, Randolph faced many of the same challenges that his predecessor, Thomas Jefferson, had attempted to address. Randolph managed the settlement of the Citizen Genêt Affair. He prompted a resumption of talks with Spain and assisted in the negotiations of the 1795 Treaty of San Lorenzo, which opened the Mississippi River to U.S. navigation and fixed the boundaries between Spanish possessions and the United States. Randolph continued Jefferson’s efforts to maintain close relations with France and minimize Alexander Hamilton’s influence over President Washington. However, Washington endorsed Jay’s Treaty, securing commercial ties with Great Britain at the expense of neutral trade, particularly U.S. shipping to France. Randolph, along with the Senate, strongly objected.

Jefferson’s August 26, 1790 circular to the consuls, reprinted here, requests “information of all military preparations, and all other indications of war which may take place in your ports…” It ends with the admonition “not to fatigue the government in which you reside, or those in authority under it, with applications in unimportant cases… and let all representations to them be couched in the most temperate and friendly terms; never indulging in any case whatever, a single expression which may irritate.”

As president, Washington proclaimed only two days of Public Thanksgiving and Prayer. The first was on October 3, 1789, just over five months after he became president. Washington celebrated the fact that the United States had emerged victorious from a long war with the world’s greatest military power, and that the nation had “Peaceably” established a new government designed to balance necessary powers with strong protections of individual rights. The danger of disunion was real, but had been avoided during the heated debate over the Constitution’s ratification, and compromise was reached with the promise of a Bill of Rights. On the same day that it had passed the first twelve amendments to the Constitution to be sent to the states for ratification, Congress requested that the president issue a Thanksgiving Proclamation.

His second proclamation, printed here, is addressed to “to all religious societies and denominations, and to all persons whomsoever.” He calls for thanks to “The Great Ruler of Nations” and “the Kind Author” of national blessings. As with his first proclamation, he does not reference Jesus Christ. While some Christian ministers criticized the omission, others believed that Washington wished to be viewed “merely as the political Head of the Union,” and not “the Dictator of its religious opinions and worship.”[1]

The Whiskey Rebellion

In celebrating “liberty with order,” Washington particularly gives thanks for the end of the Whiskey Rebellion: “the seasonable controul which has been given to a spirit of disorder, in the suppression of the late insurrection.”

Under the Constitution, direct taxes levied by Congress had to be apportioned among the states, according to a decennial census. The arguably indirect whiskey tax was free from the apportionment burden. Plus, soaking up this lucrative revenue source would deprive the states of that potential income, thus strengthening the federal government. The “Whiskey Tax,” which Congress passed on March 3, 1791, immediately stoked anger, especially on the frontier: whiskey was the most efficient way for Western farmers to process harvests into an easily transportable commodity. It was even used as a currency. The tax hit small producers hardest. Revenue collectors became as hated and reviled as British troops had been in Boston on the eve of the Revolution. A cartoon of the time, “Excise Man,” minces no words: “Just where he hung the people meet; To see him swing was music sweet; A Barrel of whiskey at his feet.”

Congress revised the act on May 8, 1792. At Hamilton’s suggestion, they reduced but did not eliminate the duties and regulations. Public outcry thus continued, and on September 15, 1792, President Washington issued a proclamation condemning those who obstructed the law. The impact of the Excise Act took several years to take full effect, however, as federal collectors were repeatedly attacked and forced—often under threat of mob violence—to resign from their positions. Unrest came to a head after subpoenas were issued in early 1794 for violators of the Excise Act, who had no intention of appearing in court. Two new Acts passed on June 5, 1794 were the final straws as long-simmering resentment flared into open rebellion. The “Whiskey Rebels” attacked a federal marshal and burned the home of a local inspector. Negotiations proved unsuccessful. Washington issued a proclamation ordering the rebels to return peaceably to their homes. He sent peace commissioners to negotiate and simultaneously began raising troops to suppress the insurrection.

On September 30, the president and Alexander Hamilton left Philadelphia to rendezvous with a federalized force of 12,950 men at Carlisle, Pennsylvania. They arrived four days later and marched with the militia to Bedford. After reviewing the troops and preparing his officers to advance when ordered, Washington returned to Philadelphia to meet with Congress. Shortly thereafter, General “Light-Horse Harry” Lee led troops into western Pennsylvania and arrested the core of the rebel army. The uprising quickly collapsed. Suppressing the rebellion represented the first real test against internal threats for the newly created Constitutional government.

America and the World

Washington gives thanks for “Our exemption hitherto from foreign war [and]—an increasing prospect of the continuance of that exemption.” When war broke out between France and Britain in 1793, America was extremely vulnerable. Britain recognized America as an ally of France (by the treaty of 1778), and both Britain and France attacked American ships. In the French Caribbean alone, American merchants eventually lost over 250 ships to British capture. America’s “perpetual” attachment to France, our first and most important Revolutionary War ally, had waned since the onset of the bloody French Revolution. The Federalists’ preferred strategy of military buildup and negotiations, however, proved inadequate. In March of 1794, Congress passed the Embargo Act, temporarily halting American shipping in order to relieve pressure on American sailors and merchants without provoking Britain.

In the short term, the Embargo protected the lives of sailors and allowed Washington’s administration time to build up the nation’s military strength and to pursue negotiations. However, like embargos before and after, it proved financially damaging to American merchants, particularly in the northeastern states, and it failed to resolve the underlying problems.

Anti-Federalists still favored France. Meanwhile, the Embargo divided Federalists who believed that asserting American sovereignty abroad depended first on enforcement of sovereign principles against all encroachers, and Anglophile Federalists who believed that unfettered access to British manufacturing technology and expanding American mercantile power would give America greater leverage. The arrival of Jay’s Treaty in America in the middle of 1795, exacerbated the political breach. Washington’s Farewell Address, issued the next year, provided a less rosy outlook than his 1795 Thanksgiving Proclamation.

Other Presidential Thanksgiving Proclamations

Presidents John Adams and James Madison also issued Thanksgiving Proclamations, but thanksgiving days more typically remained state holidays. Abraham Lincoln was the next president to issue multiple national Thanksgiving Proclamations. He began by closing government departments for a day in 1861, and in March 1863, he called for a day of “national humiliation, fasting, and prayer.” After the Battle of Gettysburg, he issued another, assigning August 6, 1863, as a day of “National Thanksgiving.” Soon after, Lincoln was moved by a letter from Sarah Josepha Hale, who had lobbied the four prior presidents unsuccessfully to make Thanksgiving the third national holiday – after Independence Day and Washington’s Birthday. On October 3, 1863, exactly 74 years after George Washington’s first presidential Thanksgiving proclamation, Lincoln proclaimed the fourth Thursday in November as a national day of Thanksgiving. President Franklin D. Roosevelt moved the holiday up a week, but in 1941 Congress fixed the date as the fourth Thursday in November, setting the precedent that remains to this day.

Complete Transcript of Washington’s Second Presidential Thanksgiving Proclamation:

By the PRESIDENT of the UNITED STATES of AMERICA,

A PROCLAMATION.

WHEN we review the calamities which afflict so many other nations, the present condition of the United States affords much matter of consolation and satisfaction. Our exemption hitherto from foreign war—an increasing prospect of the continuance of that exemption—the great degree of internal tranquillity we have enjoyed—the recent confirmation of that tranquility, by the suppression of an insurrection[2] which so wantonly threatened it—the happy course of our public affairs in general—the unexampled prosperity of all classes of our citizens, are circumstances which peculiarly mark our situation with indications of the Divine Beneficence towards us. In such a state of things it is, in an especial manner, our duty as a people, with devout reverence and affectionate gratitude, to acknowledge our many and great obligations to Almighty God and to implore him to continue and confirm the blessings we experience.

Deeply penetrated with this sentiment, I GEORGE WASHINGTON, President of the United States, do recommend to all religious societies and denominations, and to all persons whomsoever, within the United States to set apart and observe Thursday the nineteenth day of February next, as a Day of Public Thanksgiving and Prayer; and on that day to meet together, and render their sincere and hearty thanks to the Great Ruler of nations, for the manifold and signal mercies, which distinguish our lot as a nation; particularly for the possession of constitutions of government which unite, and by their union establish liberty with order—for the preservation of our peace foreign and domestic—for the seasonable controul which has been given to a spirit of disorder, in the suppression of the late insurrection—and generally, for the prosperous course of our affairs public and private; and at the same time, humbly and fervently to beseech the Kind Author of these blessings, graciously to prolong them to us—to imprint on our hearts a deep and solemn sense of our obligations to him for them—to teach us rightly to estimate their immense value—to preserve us from the arrogance of prosperity, and from hazarding the advantages we enjoy by delusive pursuits—to dispose us to merit the continuance of his favors, by not abusing them, by our gratitude for them, and by a correspondent conduct as citizens and as men—to render this country more and more a safe and propitious asylum for the unfortunate of other countries—to extend among us true and useful knowledge—to diffuse and establish habits of sobriety, order, morality, and piety; and finally, to impart all the blessings we possess, or ask for ourselves, to the whole family of mankind.

In testimony whereof I have caused the Seal of the United States of America to be affixed to these presents, and signed the same with my Hand. Done at the city of Philadelphia, the first day of January, one thousand seven hundred and ninety-five, and of the Independence of the United States of America the nineteenth.

Go: WASHINGTON.

By the President,

Edm: Randolph.

Edmund Randolph (1753-1813) was born into a prominent family in Williamsburg, Virginia. He graduated from the College of William and Mary. At the start of the American Revolution, his loyalist father returned to Britain, but Randolph joined the Continental Army as an aide-de-camp to General George Washington. From 1779 to 1782, he served as a Virginia delegate to the Continental Congress. Maintaining his legal practice, he handled a number of issues for George Washington. He also trained John Marshall; when voters elected Randolph governor of Virginia in 1786, Marshall took over his law practice. Randolph was an influential Delegate to the Annapolis Convention of 1786 and the Constitutional Convention of 1787, where he introduced the Virginia Plan and was a member of the Committee on Detail charged with framing the first draft of the Constitution. President Washington appointed Randolph as the first U.S. Attorney General in September 1789, and he provided a useful neutral voice in disputes between Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton.

When Jefferson resigned as Secretary of State at the end of 1793, Randolph succeeded him. The major diplomatic initiative of his term was the 1794 Jay’s Treaty with Britain; although Randolph had to sign it, he opposed the treaty. As a corrective, he pushed negotiations for what became Pinckney’s Treaty. Political intrigue against Randolph ended his term as Secretary of State. Hoping to neutralize Randolph’s opposition to the favorable Jay Treaty, the British government provided his opponents in Washington’s Cabinet with documents written by French Minister Jean Antoine Joseph Fauchet that had been intercepted by the British Navy. The documents were innocuous, yet Federalists in the Cabinet claimed they proved that Randolph had disclosed confidential information and solicited a bribe. Washington affirmed his support for Jay’s Treaty, and with the entire cabinet gathered, demanded that Randolph explain the letters. Randolph was innocent, but his standing with Washington was permanently weakened. Randolph resigned in 1795, and returned to Virginia to practice law. In 1807, in John Marshall’s court and to Jefferson’s great chagrin, Randolph successfully defended Vice President Aaron Burr against charges of treason.

Nathaniel Cutting (1750-1824) was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts. In 1781, he was the commander of the Elizabeth, for Nathaniel Tracy of Newbury, Massachusetts. In 1793, President George Washington appointed him as consul at the port of Havre de Grace (now called LeHavre) in the Normandy region of France. Washington also instructed him to serve as secretary to David Humphreys, the U.S. minister in Portugal, in his 1793 negotiations to prevent the Dey of Algiers from preying on American merchant ships in the Atlantic. The failure of Humphreys’ efforts led to the rebuilding of the U.S. navy to protect American ships against Barbary pirates. Cutting remained as consul at Havre de Grace until 1801. In 1816, he served as a clerk in the War Department, and in 1823, he was appointed an auditor of claims for military and bounty lands.

Additional Historic Background:

Transcript of Washington’s First Presidential Thanksgiving Proclamation

By the President of the United States of America

a Proclamation.

Whereas it is the duty of all Nations to acknowledge the providence of Almighty God, to obey his will, to be grateful for his benefits, and humbly to implore his protection and favor-- and whereas both Houses of Congress have by their joint Committee requested me “to recommend to the People of the United States a day of public thanksgiving and prayer to be observed by acknowledging with grateful hearts the many signal favors of Almighty God especially by affording them an opportunity peaceably to establish a form of government for their safety and happiness.”

Now therefore I do recommend and assign Thursday the 26th day of November next to be devoted by the People of these States to the service of that great and glorious Being, who is the beneficent Author of all the good that was, that is, or that will be-- That we may then all unite in rendering unto him our sincere and humble thanks--for his kind care and protection of the People of this Country previous to their becoming a Nation--for the signal and manifold mercies, and the favorable interpositions of his Providence which we experienced in the course and conclusion of the late war--for the great degree of tranquility, union, and plenty, which we have since enjoyed--for the peaceable and rational manner, in which we have been enabled to establish constitutions of government for our safety and happiness, and particularly the national One now lately instituted--for the civil and religious liberty with which we are blessed; and the means we have of acquiring and diffusing useful knowledge; and in general for all the great and various favors which he hath been pleased to confer upon us.

And also that we may then unite in most humbly offering our prayers and supplications to the great Lord and Ruler of Nations and beseech him to pardon our national and other transgressions-- to enable us all, whether in public or private stations, to perform our several and relative duties properly and punctually--to render our national government a blessing to all the people, by constantly being a Government of wise, just, and constitutional laws, discreetly and faithfully executed and obeyed--to protect and guide all Sovereigns and Nations (especially such as have shewn kindness unto us) and to bless them with good government, peace, and concord--To promote the knowledge and practice of true religion and virtue, and the encrease of science among them and us--and generally to grant unto all Mankind such a degree of temporal prosperity as he alone knows to be best.

Given under my hand at the City of New York the third day of October in the year of our Lord 1789.

Go: Washington

[1] David Tappan, Christian Thankfulness (Boston, 1795), quoted in Rose S. Klein, “Washington’s Thanksgiving Proclamations,” American Jewish Archives 20 (November 1968), 161.

[2] Whiskey Rebellion in western Pennsylvania, 1791-1794.