Click to enlarge:

Select an image:

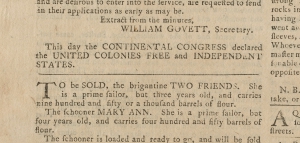

“This day the Continental Congress declared the United Colonies Free and Independent States.”

[DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE].

Newspaper.

Pennsylvania Evening Post, Tuesday, July 2, 1776, (vol. II, no. 226). Philadelphia: Printed by Benjamin Towne. Prints notice of the July 2nd Independence resolution on the final page. 4 pp. 8¾ in. x 10 7/8 in.

Inventory #23205

SOLD — please inquire about other items

This same-day report of the Congressional resolution declaring independence is the earliest known printed notice of its kind. The brief, but momentous announcement appears on the last page of a newspaper issue fraught with high drama. Among the notable names appearing here in other news are Washington, Jefferson, Hancock, Howe and Burgoyne; news reports cover everything from the British fleet lurking off New York, to daring privateers, Continental Army movements, the execution of one of Washington’s guards for treason, Indians, cannibalism, and much more.

This issue of the Pennsylvania Evening Post is rare. We have been able to identify only three or four sales at auction over the last century, and all were in larger runs of the newspaper.

Condition

Strong, clear impression; untrimmed, original deckled edges. Printed on an imperfectly made sheet with a 2¼ x ½ in. missing section in one corner (pages 1-2) but well clear of any text. Apparently washed in previous conservation treatment, but otherwise a fine copy.

In addition to the notice of Independence, this issue includes:

-

Virginia’s election of delegates to the next session of Congress, including Richard Henry Lee, who had first introduced the independence resolution, and Thomas Jefferson, who had drafted the Declaration of Independence.

-

an account of the execution, in the presence of 20,000 New York spectators, of “a soldier [Thomas Hickey] belonging to his Excellency George Washington’s guards, for mutiny and conspiracy…that horrid plot of assassinating the Staff officers, blowing up the magazines, and securing the passes of the town on the arrival of the hungry ministerial myrmidons.”

-

news of the British fleet off of New York, and a report that the American troops in New York will soon number 25,000.

-

June 21-22 proceedings of Pennsylvania’s Provincial Conference, with a transcription of a Congressional memo by Robert Morris regarding “raising six thousand militia for establishing a flying camp.”

-

a Congressional resolve, over the printed signature of John Hancock, calling for the raising of a German battalion, followed by the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety’s resolution to carry out recruitment.

-

news from London, including payment of Hessian mercenaries destined for America, Burgoyne’s plans against New England, and the opinion that sending cavalry to America would be “laughable, if the consequences were not so serious.”

-

reports from Halifax of the British fleet bound for America, and the sailing of a British convoy carrying former colonial officials evacuated from Boston.

-

reports from Canada of starvation and cannibalism, and of the determination of local Indians to join the American cause.

-

Rhode Island’s passage of an act permitting the construction of smallpox inoculation hospitals.

-

Connecticut’s production of saltpeter for the manufacture of gunpowder.

-

proposed changes in copper coinage.

-

privateering reports from around the colonies.

-

advertisements for runaway slaves and indentured servants, as well as sale notices for ships, a stage-boat service, alcohol, tea, cloth, and “two CANNON, four pounders.”

Historical Background

On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee, a Virginia delegate to the Second Continental Congress, proposed a resolution calling for American independence. The Congress appointed a Committee of Five – John Adams, Roger Sherman, Benjamin Franklin, Robert Livingston, and Thomas Jefferson – to draft an appropriate message. Written by Jefferson, with minor edits by Franklin and Adams, the draft was submitted to Congress on June 28.

Not all in Congress favored independence. George Read of Delaware voted against Lee’s resolution. Thomas McKean, another Delaware delegate, sent a message to Caesar Rodney (the third member of the Delaware delegation) to come quickly to Philadelphia to break their state’s tie. The 47-year-old Rodney received the dispatch on July 1 and proceeded to ride 80 miles non-stop from his home near Dover, Delaware, to Philadelphia. He arrived just in time to make the vote on Tuesday, July 2, 1776, when the Continental Congress took a decisive step by passing Lee’s resolution “That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.” With this brief resolution, the 13 colonies severed their imperial bond with Great Britain.

The importance of the Congressional action was trumpeted by John Adams when, on Wednesday, July 3, he wrote to his wife Abigail that he considered July 2 the date of independence:

The Second Day of July 1776, will be the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival. It ought to be commemorated, as the Day of Deliverance by solemn Acts of Devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.

In another letter of the same date, Adams again discussed the resolution for independence:

Yesterday the greatest Question was decided, which ever was debated in America, and a greater perhaps, never was or will be decided among Men. A Resolution was passed....You will see in a few days a Declaration setting forth the Causes, which have impell’d Us to this mighty Revolution.

In the two days following the resolution of independence, Congress continued to struggle with the wording of the final Declaration. Though some revisions were made (in particular, striking the provision calling for abolition of the slave trade), it remained essentially Jefferson’s prose. On Thursday, July 4, the delegates of 12 of the 13 states agreed to the final text of the Declaration, pledging “to each other our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor” to uphold its principles. The approved manuscript, now lost, was no doubt signed by Continental Congress president John Hancock and secretary Charles Thomson. It was then taken to printer John Dunlap, presumably by a member of the Committee of Five that had been ordered to supervise its publication.

Just four days after publishing the first notice of independence, the Pennsylvania Evening Post once again scooped the news, becoming the first newspaper to print the text of the Declaration. Towne’s Saturday, July 6, publication was preceded only by the Dunlap broadside, published on July 5. Towne even beat Dunlap’s own newspaper, the Pennsylvania Packet, by two days.

Benjamin Towne (?-1793) of Lincolnshire, England, arrived in Philadelphia in 1769. He joined the Pennsylvania Chronicle, a loyal Whig newspaper, but quit after his backers pulled out following his publication of patriot John Dickinson’s Letters of a Pennsylvania Farmer. On January 24, 1775, he began publishing the Pennsylvania Evening Post, the fourth English newspaper in the city, its first tri-weekly paper, and the only evening newspaper.

Politically, Towne was clearly a pragmatist. He espoused patriot ideals when he opened his Philadelphia print shop, but when the British occupied the city on September 26, 1776, he became a Royalist in time for his next publication. When the British evacuated the city seven months later, Towne reverted to the patriot banner. In 1778, when the city’s military fortunes again shifted, Towne began publishing the Royal Pennsylvania Gazette, lasting only 25 issues. As the other newspapers either evacuated or suspended publication, Towne’s fluid sense of loyalty allowed him to remain the sole newspaper publisher in Philadelphia. Nonetheless, his opportunism marked him as disloyal, and he was “attainted” for treason in 1778, although the charges were later dropped.

In addition to Towne’s first printing of America’s founding document, he was intimately involved in publishing other important Revolutionary-era documents, and generated controversy in doing so. Towne’s Pennsylvania Evening Post was the first newspaper to print the Virginia Declaration of Rights on June 6, 1776. His newspaper also printed Thomas Paine’s American Crisis that December. Towne was at the center of Paine’s disagreement with original Common Sense publisher Robert Bell. After Bell reprinted an unauthorized edition of Common Sense, Paine jettisoned his original publisher and instead engaged William and Thomas Bradford to re-publish the pamphlet. The Bradfords contracted with Styner & Cist (publishers of the Pennsylvania Journal) and with Towne to each print 3,000 copies. The acrimony between Bell and the Bradford brothers is well documented in the dueling advertisements and editorial comments found in Towne’s newspaper.

On May 30, 1783, Towne turned the Pennsylvania Evening Post into the first daily newspaper in the United States. However, with Towne branded a traitor and forced to hawk his own papers on the street, the newspaper collapsed the following year. John Dunlap and David Claypoole then made their Pennsylvania Packet the first successful daily on September 21, 1784.

PUBLISHED NOTICES OF INDEPENDENCE[1]

July 2 Pennsylvania Evening Post (Philadelphia) [the present example]

“This day the Continental Congress declared the United Colonies Free and Independent States.” (p. 4)

July 3 Die Germantowner Zeitung (Germantown)

Yesterday the Continental Congress declared the United Colonies Free and Independent States. [in German]

Pennsylvania Journal (Philadelphia)

“Yesterday, the Continental Congress declared the United Colonies free and independent states.”

Pennsylvania Gazette (Philadelphia)

“Yesterday, the Continental Congress declared the United Colonies free and independent states.”

July 4-5 ca. Pennsylvania Magazine: or American Monthly Museum (Philadelphia)

“July 2. This day the Hon. Continental Congress declared the United Colonies Free and Independent States.” (June 1776 issue, p. 296)

July 5 Pennsylvanischer Staatsbote (Philadelphia)

Yesterday the honorable Continental Congress declared the United Colonies free and independent states. The declaration is now in press in English; it is dated July 4, 1776, and will be published today or tomorrow. [in German] (p. 2)

July 6 Constitutional Gazette (New York)

“New York, July 6 / On Tuesday last theContinental Congress declared the United Colonies Free and Independent States.” (p. 3)

July 8 New-York Gazette (New York)

“Philadelphia, June [sic] 3 / Yesterday the Congress unanimously Resolved to declare the United Colonies Free and Independent States.” (p. 3)

July 10 Connecticut Journal (New Haven)

“To morrow, will be ready for sale, The Resolves of Congress, declaring the United Colonies, Free and Independent States.” (p. 2)

July 10 Massachusetts Spy (Worcester)

“Worcester, July 10 / It is reported that the Honorable Continental Congress have declared the American Colonies Independent . . . Which we hope is true.” (p. 3)

[1] Includes notices of either the July 2, 1776 resolution or of the July 4, 1776 Declaration, but prior to the publisher’s receipt of the actual Declaration text.