|

The Gettysburg Address, Including First Day Printings |

Lincoln’s speech, delivered at Gettysburg National Cemetery on November 19, 1863, has endured as a supreme distillation of American values. Over the past 150 years, it has become a compelling testament to the sacrifices required to achieve freedom for all Americans. Lincoln made his speech at the cemetery’s dedication, some four months after the bloody and pivotal battle that turned the tide of the Civil War in favor of the Union. Edward Everett, the most famous orator of his day, spoke first, and his address took some ninety minutes to deliver. He evoked the ancient Greeks, who saved their society by defeating the Persians at Marathon, drew upon Wellington’s victory over Napoleon at Waterloo, and then moved to a history of the Battle of Gettysburg—America’s decisive victory in the struggle to save the nation. Though a masterpiece of the period, it has been largely forgotten.

Historical Background

|

To see our rare first day printings of the Gettysburg Address and other Gettysburg-related items, click here. |

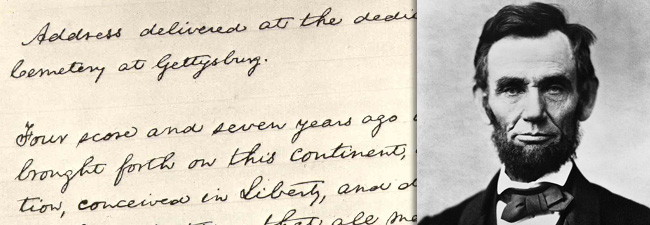

Lincoln’s speech, delivered in only a few minutes, has persisted despite his assertion that “the world will little note nor long remember what we say here.” Much has been written about Lincoln’s famous speech, from whether he read it or memorized it to when and where he wrote it. Many Americans believe Lincoln wrote the speech on the back of an envelope while riding the train to Gettysburg. This charming piece of fiction originated in Mary Shipman Andrews’s 1906 book, The Perfect Tribute. The real Address’s writing is more complex. When Secretary of State William Seward gave a prepared speech on the evening of November 18, he gave a copy to the Associated Press. Reporters then repeatedly harassed John Hay, one of Lincoln’s personal secretaries, for a copy of the President’s speech. Hay demurred, having neither the text nor any idea when it would be available. Based on the paper Lincoln used for his two drafts (one page of Executive Mansion stationery and a page of lined paper, then 2 identical pages of lined paper), historian Gabor Boritt has concluded that the “likelihood remains that having written the first part of his speech in Washington, Lincoln finished his First Draft in the evening in Gettysburg, and then hurriedly wrote his Second Draft the next morning” (Boritt 273). The text of the second draft is closest to the words recorded by reporters at the scene, and is generally considered to be Lincoln’s reading copy.

|

|

|

Engraving of the dedication ceremony, from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. |

Newspaper copies and reports are another story, one complicated by the fact that most witnesses to the dedication ceremony and speech outlived Lincoln by decades. But the words he spoke at Gettysburg only gained traction as his seminal contribution in the 1880s. As both the Lincoln legend and the speech’s significance grew following the Civil War, Reconstruction, the Centennial, and the rise of Jim Crow, many more people than could have been possibly involved in the event have staked their claims to a Gettysburg Address connection.

|

|

|

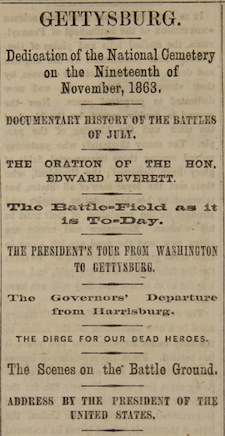

Headlines from the Philadelphia Press, November 20, 1863.

|

With the advent of the telegraph, news reporting had become big business, and Lincoln surrounded himself with the press corps. Roy Basler, editor of the Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, noted four reporters making shorthand notes of the speech: Associated Press and New York Herald reporter Joseph Gilbert, Boston Daily Advertiser reporter Charles Hale, and reporters from the Chicago Tribune and Philadelphia Enquirer. Gabor Boritt, author of the definitive The Gettysburg Gospel, adds John Hay, one of Lincoln’s personal secretaries, to the list, and refers to at least 23 additional reporters on the scene, including many of Lincoln’s allies in the Republican press. Known as “Lincoln’s dog,” Philadelphia Press owner John Forney offered a drunken pro-Lincoln rant on the evening before the speech, but he was sober enough to wait for a slew of correspondents to arrive to take down his words.

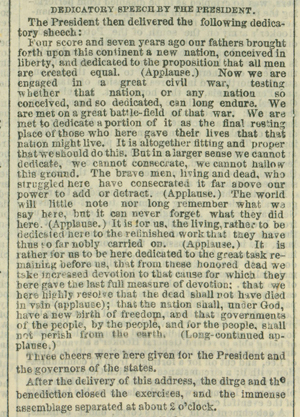

What has come down as the standard version of the Address was compiled from Lincoln’s drafts, reports of what he spoke at the time, and later revisions made by Lincoln himself. What is certain, however, is that “variations of [the AP] version reached more Americans in 1863 than any other” (Boritt 239). The New York Herald received the text by telegraph, and published it the next day. Later, when Lincoln penned copies of his speech, he is said to have referenced the AP report.

A longtime story credits Joseph I. Gilbert[1] of the Associated Press as having had “actually consulted Lincoln’s delivery text briefly after the ceremony.” This, noted Garry Wills in 1992, “makes his version more authoritative for some scholars.” Wills correctly credits the AP text as authoritative, and in terms of cultural significance, no other version had the reach of the AP’s wording. The AP version and its slight variants (usually comma placement and capitalization) are easily identifiable because of the phrase “dedicated here to the refinished work…” rather than the correct “unfinished work.” However, Gilbert’s claim to be the reporter who delivered the AP’s text does not withstand scrutiny. Gilbert did work for the AP at the time of the speech, but he only made his assertion in 1914. In the ensuing fifty-four years, the event’s stature had grown to near-Biblical proportions. Gilbert recalled being so taken with Lincoln’s words that he stopped recording the speech in shorthand. He claimed the President fortuitously allowed him to look at the manuscript copy, and Gilbert insisted that “the press report was made from the copy no transcription from shorthand notes was necessary (Boritt 371). However, the AP version missed the word “poor,” which other reporters caught and was present in the second draft; it also contained the phrase “under God,” which was absent from the draft, and notes five interruptions for applause, followed by sustained applause at the speech’s conclusion. When asked in 1917, Gilbert denied hearing any applause at all. These and other critical elements of the AP text cast serious doubt on Gilbert’s claims to have copied Lincoln’s manuscript notes.

Gabor Boritt writes that Boston Daily Advertiser reporter Charles Hale’s eyewitness, handwritten version should be preferred since it relied only on what Lincoln said; although one could counter-argue that he may not have captured Lincoln’s words exactly. Both Boritt and Wills agree that while many other reporters’ transcripts are generally inferior, they nevertheless captured the word “poor” that both the AP and Hale missed. Interestingly, when Hale’s paper, the Boston Daily Advertiser, first published the Address on November 20, the paper incorrectly printed “The world will note nor long remember, what we say here, but it can never forbid what they did here,” omitting the word “little” before “note” and changing “forget” to “forbid” —an odd discontinuity for a claim to the authoritative text, though the reporter lamented that the speech had “suffered somewhat at the hands of telegraphers.” The Boston Evening Transcript picked up the morning paper's text—and the error.

|

|

|

Detail from The World, New York, November 20, 1863, with the Associated Press version. |

Versions printed on November 20, 1863 are the Address’s first appearance anywhere and are highly desirable, as are other early printings. The Washington Daily Chronicle, also owned by John Forney, published Edward Everett and Lincoln’s speeches in their November 20 edition, and on November 22 came out with a 16-page pamphlet entitled “The Gettysburg Solemnities,” which contained a number of the day’s speeches including the first separate (outside of a newspaper) printing of Lincoln’s speech. There are only three known copies of the pamphlet (a fourth disappeared from a library), the last one on the market having sold at auction and then resold privately for approximately $650,000. The first publication in book form, printed by Baker and Godwin of New York, was entitled An Oration Delivered on The Battlefield of Gettysburg, (November 19, 1863,) at the Consecration of the Cemetery Prepared for the Interment of the Remains of Those Who Fell in the Battles of July 1st, 2d, and 3d, 1863 it also appeared within the week. Copies have sold privately for over $30,000.

Gettysburg Address Manuscripts

Five manuscript versions written in Lincoln’s hand are known. Library of Congress.

1. First draft, the Nicolay copy after Lincoln’s personal secretary John Nicolay. Library of Congress.

2. Second draft, the Hay copy, after Lincoln’s personal secretary John Hay.

Much ink has been spilled over which of the first two was the copy Lincoln read; the answer is probably neither.

Three more versions were written later for charitable purposes, and more closely approximate the words that Lincoln actually spoke.

3. The copy given to Edward Everett was intended as a fundraiser for the New York Metropolitan Fair; it is now at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library in Springfield, Illinois.

4. George Bancroft requested a copy to be lithographed and sold at the Baltimore Sanitary Fair to support the troops. Lincoln agreed, but did not pen a title or signature, and ran into the margins. Cornell University.

5. Because the Bancroft copy was impractical to reproduce, Lincoln penned another adding the title and his signature. This, known as the Bliss copy, after Bancroft’s stepson, is at the White House.

_________________________________________________________________

Sources

Roy Basler, ed., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Vol. VII (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers, 1953).

Don E. Fehrenbacher, ed., Abraham Lincoln: Speeches and Writings, 1859-1865 (New York: Library of America, 1989).

Garry Wills, Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words that Remade America (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992).

Gabor Boritt, The Gettysburg Gospel: The Lincoln Speech that Nobody Knows (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2006).

Kent Gramm, “A More Perfect Tribute.” https://www.historycooperative.org/journals/jala/25.2/gramm.html#REF1

[1] Early on, Gilbert was misidentified as Joseph L. Gilbert. (Boritt 371).

|