|

The Myth of Non-Emancipation |

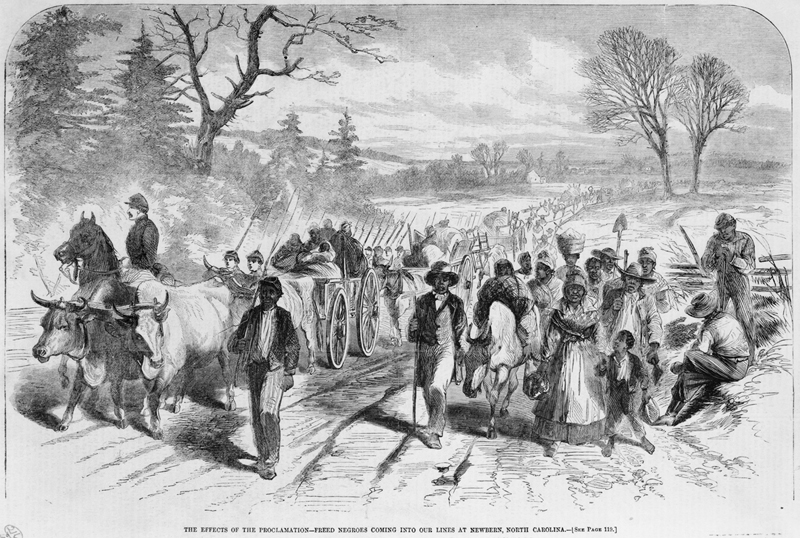

The Emancipation Proclamation has faced criticism as a document of little impact because it offered freedom only to slaves “within any state or designated part of a state … in rebellion against the United States,” rather than to slaves in areas that the Union actually controlled. That charge does not withstand scrutiny. By freeing slaves in rebel-held territory, the Proclamation effectively turned Union forces into an army of liberation. Rather than retreating behind arguments that slavery was a state issue, or returning escaped slaves under the Fugitive Slave Act, the federal government, for the first time, acted to guarantee the freedom of African Americans. The “government of the United States,” read the Proclamation, “including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons.” While the Emancipation Proclamation’s reach was limited by exceptions (loyal border states, all of Tennessee, and certain Louisiana parishes), “emancipation was immediate,” Eric Foner has written, in Union-occupied parts of Arkansas, Florida, North Carolina, Mississippi and the South Carolina Sea Islands. “Overall,” he points out, “tens of thousands of slaves—50,000 according to one estimate—gained their freedom with the stroke of Lincoln’s pen.”

|

|

|

Freedmen and women liberated as Union forces march south, Harper's Weekly, February 21, 1863. |

Many prior presidents had imagined or hoped for a nation without slavery, but could not, or would not, act on their ideals. Thomas Jefferson famously wrote, “I see not how we are to disengage ourselves from that deplorable entanglement, we have the wolf by the ears and feel the danger of either holding or letting him loose. I shall not live to see it but those who come after us will be wiser than we are….”

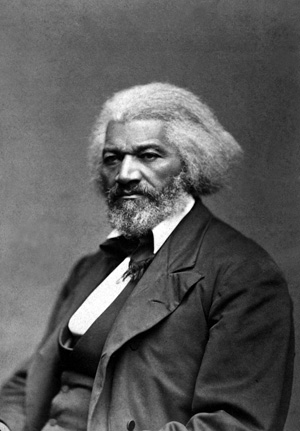

With the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln dramatically tied the Union’s war aims to the ultimate goal of putting an end to slavery. Whether they approved or not, after January 1, 1863, Americans could no longer deny that emancipation was central to the Union war effort. “We shout for joy that we live to record this righteous decree,” wrote Frederick Douglass. From black soldiers, to European statesmen, to Lincoln’s Northern political enemies, to outraged Southern rebels, observers understood that America was could no longer ignore the ideals expressed in the Declaration of Independence.

|

|

Frederick Douglass |

As the war dragged on, the “military necessity” of emancipation grew more apparent, and African Americans became instrumental in forcing Lincoln and the Northern public to make freedom a central goal of the war. In historian Ira Berlin’s words, Lincoln and the slaves played “complementary roles” in bringing about emancipation:

By abandoning their owners, coming uninvited into Union lines, and offering their assistance as laborers, pioneers, guides, and spies, slaves forced federal soldiers at the lowest level to recognize their importance to the Union’s success. That understanding traveled quickly up the chain of command. In time, it became evident even to the most obtuse federal commanders that every slave who crossed into Union lines was a double gain: one subtracted from the Confederacy and one added to the Union. The slaves’ resolute determination to secure their liberty converted many white Americans to the view that the security of the Union depended upon the destruction of slavery.

Perhaps no one understood the implications of the Emancipation Proclamation better than Frederick Douglass. Never one to mince words regarding freedom and equality for his race, he marveled at the changes brought about by Lincoln’s act and saw immediately the long-term consequences for African Americans.

Slavery is now in law, as in fact, a system of lawless violence, against which the slave may lawfully defend himself.…The change in attitude of the Government is vast and startling. For more than sixty years the Federal Government has been little better than a stupendous engine of Slavery and oppression, through which Slavery has ruled us, as with a rod of iron.…Assuming that our Government and people will sustain the President and the Proclamation, we can scarcely conceive of a more complete revolution in the position of a nation.…I hail it as the doom of Slavery in all the States.

|

|

|

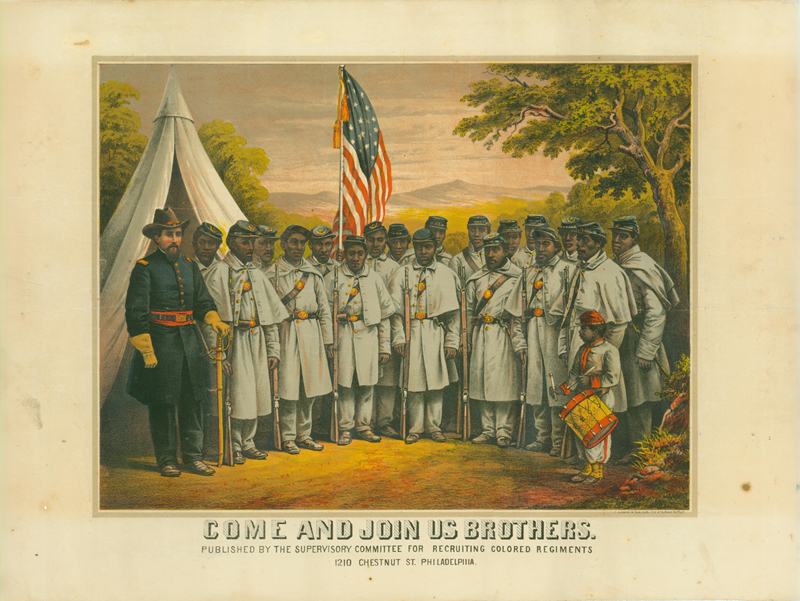

Recruiting black soldiers after Emancipation (African American Civil War Memorial and Museum) |

The Emancipation Proclamation redefined the role of the federal government in relation to African Americans. It altered war goals, immediately freed nearly 50,000 slaves in Union-held parts of the Confederacy, and offered freedom to slaves as the Union Army pushed further into rebel territory. Its contemporary detractors saw it as an act to free slaves, while supporters, including African Americans’ most eloquent spokesman, considered it a sea change for the nation. It is a clear fallacy that Lincoln’s bold action emancipated no one.

Next Page: The Proclamation and Black Troops

|