|

Affirming Slavery’s Role in Precipitating the War |

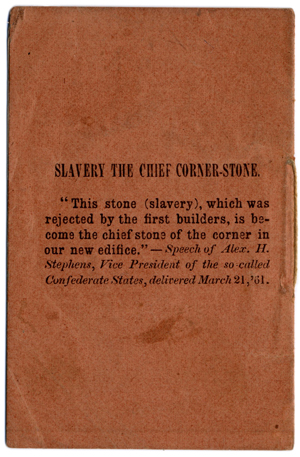

The question of slavery’s role in bringing on the Civil War has provoked one of the most vehement debates in American history. Many Southerners have argued that Confederates went to war not to defend slavery but to protect states’ rights. That argument falls flat, however. Southerners looked to Constitutional protections of slavery as the foundation of many of their arguments, and after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, demanded the use of federal marshals to return their runaway slaves. Southern leaders readily admitted the centrality of slavery to most states’ rights disputes, as well as to secession itself. Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens was only stating the obvious when, in March 1861, he called slavery the “cornerstone” of the Confederacy:

|

|

|

Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens endorses slavery; printed on the back of the miniature Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. |

The new [Confederate] constitution has put at rest, forever, all the agitating questions relating to our peculiar institution. African slavery as it exists amongst us the proper status of the negro in our form of civilization....Though not incorporated in the [U.S.] constitution [its framers] rested upon the assumption of the equality of races. This was an error....Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its corner- stone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.

The Confederate Constitution’s only major revisions to the U.S. Constitution addressed slavery: “No bill of attainder, ex post facto law, or law denying or impairing the right of property in negro slaves shall be passed” (Article I, Section 9). In all new territory, “the institution of negro slavery, as it now exists in the Confederate States, shall be recognized and protected by Congress and by the territorial government” (Article IV, Section 3).

The antebellum South had evolved from a society with slaves to one in which every aspect of the social order revolved around slavery. Wealthy slaveholders formed the majority of the South’s state and national legislators. Slaves were crucial to both the agricultural and industrial labor forces, and many white Southerners whose names were never entered in the census as slave owners regularly depended on hiring or borrowing slaves. Moreover, most white Southerners feared the potential social consequences of emancipation, predicting everything from crime waves, to “miscegenation” (racial intermarriage), to the loss of their labor force, to black demands for citizenship. Ending slavery would pose a significant threat to the wealthy and commoners alike: a total reordering of Southern society. Civil War-era Southerners might well be surprised by modern descendants who dismiss those facts and reject slavery as the cause of the war.

During the war, slavery created additional class tensions within the Southern union, notably when a law exempted owners of twenty or more slaves from the draft. As the Confederacy’s fortunes grew more desperate in the second half of the war, Southerners even debated arming slaves, with emancipation and land as potential rewards. However, the concept of arming black men, and rewarding them with freedom for themselves and their families, was too fundamental a challenge to Southern ideas of manhood, citizenship, and race.

Seizing the Moment

Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation as soon as the exigencies of war first made the radical step of abolition possible. Even though he realized that it might cost him re-election, by 1864 he insisted on both reunion and emancipation as preconditions to any peace negotiation. Though the battle for civil rights would have to follow, Lincoln rightly regarded the Proclamation as “the central act of my administration, and the great event of the nineteenth century.”

|

|

|

Detail of the masthead from William Lloyd Garrison's abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator. Its motto was "No Union With Slaveholders." |

Next Page: Appendix I: The Leland-Boker “Authorized Edition” of the Emancipation Proclamation

|