|

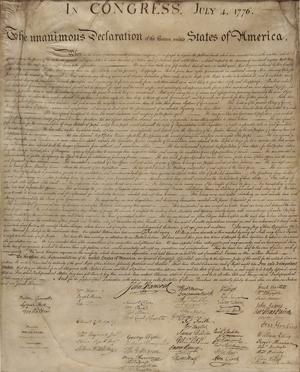

The Declaration of Independence—William J. Stone Engraving |

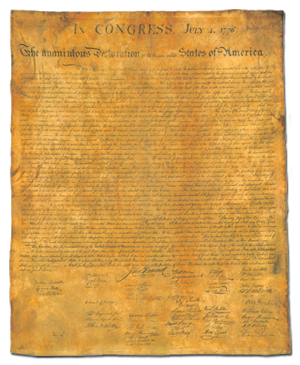

DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE. William J. Stone, Copperplate engraving on vellum, First Edition. 24 3/4 x 30 5/16 in.

Historical Background

All of the July broadsides and newspapers were created before what we now think of as the “original manuscript.” On July 19, 1776, Congress ordered an official copy of the Declaration to be engrossed on vellum and signed by the members. Timothy Matlack, the clerk of Secretary of Congress Charles Thomson, was chosen to copy the text of the Declaration onto a large vellum sheet, which would then be signed by the delegates. The title of the Declaration was changed to “The Unanimous Declaration of the Thirteen United States of America,” after New York voted for independence on July 9.

On August 2, 1776, it was recorded in the Journal of Congress that “the declaration of independence being engrossed and compared at the table was signed” by the members of Congress then assembled. The order of signatures proceeded geographically, the delegates from New England signing first. Several delegates not present signed later. A couple of the signers had not been members of Congress on July 4; Thomas Lynch, Jr., for instance, replaced his father who had passed away in the meantime.

|

Own a Piece of History. To see our current inventory of copies of the Declaration of Independence and Declaration signers related material click here.

|

|

|

|

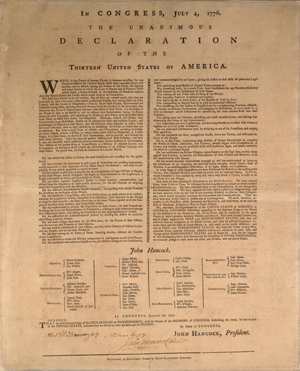

This 1777 broadside, printed by Mary Goddard, was the first to reveal the names of the signers of the Declaration. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.) |

The names of the signers remained unknown for the most part until 1777. After the decisive battles of Trenton and Princeton, Congress on January 18, 1777, ordered an authenticated copy of the Declaration printed for distribution to the states, complete with signer’s names. Baltimore printer Mary Katherine Goddard produced these copies, and, after being signed by John Hancock and Charles Thomson, at least one was sent to every state. Only nine of the Goddard broadsides are known to exist, some signed by Hancock and Thomson.

|

|

|

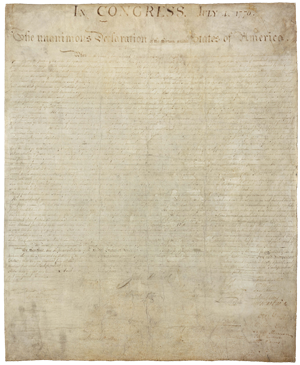

The condition of the engrossed vellum copy of the Declaration has deteriorated to the point where it is barely legible. |

The engrossed Declaration is presumed to have travelled with the Continental Congress as it met in various Eastern cities. If so, it would have gone from Philadelphia, to Baltimore, back to Philadelphia, then to Lancaster and York, Pennsylvania, and then back to Philadelphia for the remainder of the Revolution. The Continental Congress then met in Princeton, New Jersey (1783), Annapolis, Maryland (1783-1784), Trenton, New Jersey (1784), and New York City (1785-1790). It continued to be held by Congress until March 1790, when Thomas Jefferson assumed his position as the first Secretary of State and the department took charge of “the Acts, Records, and Seal of the United States.”

The precious document was frequently unrolled for display to visitors, and the signatures, especially, began to fade after nearly fifty years of handling. More damage followed, caused by the effects of aging and exposure to sunlight and humidity as the Declaration hung unprotected on a wall in the Patent Office for thirty-five years. At the time of the Centennial, efforts at preservation and conservation belatedly began. By 1876, however, the manuscript was thus described in the Philadelphia Public Ledger: “The text is fully legible, but the major part of the signatures are so pale as to be only dimly discernible in the strongest light, a few remain wholly readable, and some are wholly invisible, the spaces which contained them presenting only a blank.”

Fortunately, in 1820, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams grew concerned over the fragile condition of the Declaration. With the approval of Congress, Adams commissioned William J. Stone to engrave a facsimile—an exact copy—on a copper plate. Stone’s engraving is the best representation of the Declaration as the manuscript looked prior to its nearly complete deterioration.

|

|

|

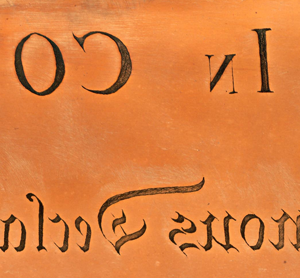

A detail from copper plate created by W.J. Stone. Like all copperplate engravings the image on the plate is reversed.

|

First Edition of the Stone Facsimile in 1823

William J. Stone’s Declaration was engraved on copperplate and printed on vellum, a parchment sheet made from calfskin. The engraving is as close to an exact copy of the original manuscript as was humanly possible at that time, before the use of photographic imagery. Stone worked on the engraving for close to three years, keeping the original in his shop. Many still believe he used some sort of wet or chemical process to transfer the ink to create such a perfect reproduction, thus hastening the destruction of the original manuscript. In fact, he left minute clues to distinguish the original from the copies, also providing evidence of his painstaking engraving process. Stone’s engraving is the best representation of the Declaration manuscript as it looked at the time of signing. On April 11, 1823, Adams noted a visit from “Stone the Engraver, who has finished his fac-simile of the original Declaration of Independence.” By May 10, the original engrossed manuscript was back in Adams’s hands, being shown to visitors.

Daniel Brent of the Department of State wrote to Stone on May 28, 1823, requesting 200 copies of the facsimile “from the engraved plate…now, in your possession, and then to deliver the plate itself to this office to be afterwards occasionally used by you, when the Department may require further supplies of copies from it.” Stone proceeded to print 201 copies on vellum, one of which he kept for himself, as was customary though perhaps not authorized in this case. Four copies presently known on heavy wove paper are most likely proofs before printing on the much more expensive vellum.

|

|

|

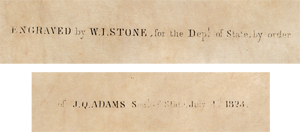

The top left and right sections of the imprint on the vellum copies printed by W.J. Stone.

|

On May 26, 1824, Congress provided orders to John Quincy Adams for distribution of the Stone facsimile for distribution. The surviving three signers of the Declaration, Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and Charles Carroll of Carrollton, each received two copies. Two copies each were also sent to President James Monroe, Vice President Daniel D. Thompkins, former President James Madison, and the Marquis de Lafayette. The Senate and the House of Representatives split twenty copies. The various departments of government received twelve copies apiece. Two copies were sent to the President’s house and to the Supreme Court chamber. The remaining copies were sent to the governors and legislatures of the states and territories, and to various universities and colleges in the United States.

|

|

|

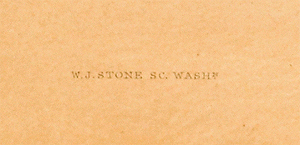

The imprint at the bottom left of the paper copies that Stone printed for Peter Force.

|

All subsequent exact facsimiles of the Declaration descend from the Stone plate. One of the ways to distinguish the first edition is Stone’s original imprint, top left: “ENGRAVED by W.I. STONE, for the Dept. of State, by order,”and continued across the top right: “of J. Q. ADAMS, Sect. of State, July 4th, 1823.” Sometime after Stone completed his original printing, his imprint at top was removed, and replaced with a shorter imprint at bottom left, “W. J. STONE SC WASHn,” just below George Walton’s printed signature.

|

|

Privately Owned - Tennessee Thrift Shop |

Discovered in a Thift Shop in Tennessee

In 2006, this copy of the first “exact facsimile” of the Declaration was cleaned out of a garage and donated to a thrift shop, where it sold for the thrift shop “standard price” of $2.48. The buyer researched it, had it authenticated, and sent it to a top conservator. He then sold in 2007 at Raynor’s Historical Collectible Auction, for $477,000. After post-discovery press, the donor came forward (“I was the idiot,” he said). He explained that cleaning out the garage was part of his recent pre-marriage negotiation. Out went a great deal of junk—along with the Declaration that he had bought it at a flea market for $10 a decade earlier). We acquired this document for a client in 2008.

For the census of the Stone printing, click here

|