|

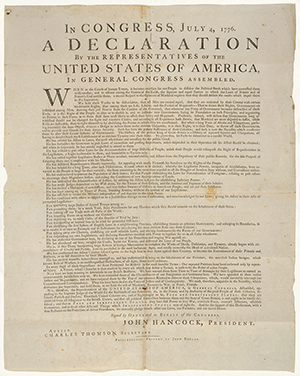

The Declaration of Independence: Dunlap’s July 4, 1776 Broadside |

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal…” “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal…”

[DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE]. Broadside. Philadelphia: John Dunlap. First printing, July 4-5, 1776.

We were the underbidder when the last copy on the market first sold at Sotheby’s in 1991. We acquired it in 1993, but held it all too briefly. It came back to Sotheby’s again in 2005, when we were outbid by Norman Lear. Lear sold it privately in 2011, right after completing a 50-state tour.

There are many excellent replicas of the Dunlap Declaration. In the hope that the next original will come to us, we are happy to review copies if you think you may have an original Dunlap. Email us a picture, and the size, to real@sethkaller.com

The First News of Independence

With a very brief resolution on July 2, 1776, the Continental Congress in Philadelphia boldly proclaimed the United States to be “Free and Independent” from Great Britain. The delegates then began debating the formal Declaration text, which passed on July 4. Pledging their lives, fortunes, and sacred honor to uphold the principles put forth, the approved Declaration was then signed by only two men, Continental Congress President John Hancock and Secretary Charles Thomson (often misspelled “Thompson,” as in the present example) and taken to the office of printer John Dunlap. The Congressional committee responsible for writing the Declaration was ordered to supervise its publication. (Many assume that Jefferson was the one who supervised the printing at Dunlap’s, but it actually was John Adams).

Broadsides such as this fanned the flames of independence. Passed from hand to hand, read aloud at town gatherings, or posted in public places, broadsides (single pages with print on only one side) were meant to quickly convey news. In a way, Declaration broadsides are even more “original” than the signed manuscript pictured by most Americans. This is not yet “The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States,” but rather “A Declaration, by the Representatives of the United States of America, in General Congress assembled.” On July 4, New York’s delegation abstained from voting for independence. After replacing their delegates, New York joined the other 12 colonies.

Moreover, as printed here, the July 4 Declaration was signed by only two men: Continental Congress President John Hancock and Secretary Charles Thomson (here with the common variant “Thompson”). After New York came on board, Congress resolved on July 19 to have the Declaration engrossed with a new title: “The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America.” Most of the 56 signers affixed their names on the engrossed document on August 2, 1776, with some added even later.

On the morning of July 5, Dunlap delivered the freshly-printed copies to Congress. Over the next few days, John Hancock sent the official broadside to the thirteen former colonies and to General George Washington and other military commanders. (We’ve been honored to have handled two of Hancock’s original cover letters transmitting Dunlap Declarations).

Meanwhile, on July 6, the Pennsylvania Evening Post became the first newspaper to print the text. The Signers sent Declaration copies to their families, friends, and associates, as did private individuals and members of the press.

During the next few weeks, the Declaration was re-published throughout the country in locally-printed broadsides and newspapers, both official and unofficial. Public readings were followed by huzzahs, thirteen-gun salutes, parades, toasts, and often times, boisterous mobs that committed monarchial symbols to the bonfire.[1]

It took five days for George Washington, with the army in New York, to learn that the Continental Congress formally declared America’s independence from Great Britain. On July 9, 1776, he received a letter from Hancock, along with Dunlap copies of the newly approved Declaration. The commander-in-chief had additional copies made by orderlies and distributed to his brigadier generals and colonels, and read to his troops at 6:00 that evening, at City Hall Park. Later that night, a boisterous crowd of soldiers, sailors and local citizens headed to Bowling Green, toppled the huge, gilt lead equestrian statue of George III, and dragged it down Broadway. It was then taken away, and most of the statue was melted down. Ebenezer Hazard brilliantly remarked that the British “troops will probably have melted majesty fired at them,” and indeed the King was eventually transformed into 42,088 bullets. (Lossing: 595; The New York Historical Society has the largest surviving fragments). In any case, the next day General Washington voiced disapproval, noting that though the destruction was “actuated by Zeal in the public cause … it has … the appearance of riot, and want of order … in future these things shall be avoided by the Soldiery, and left to be executed by proper authority” (George Washington, July 10, 1776, General Orders).

|

Own a Piece of History. To see our current inventory of copies of the Declaration of Independence and Declaration signers related material click here.

|

References

American Memory. Library of Congress. memory.loc.gov

Brigham, Clarence S. History and Bibliography of American Newspapers, 1690-1820 (Worcester, Mass: American Antiquarian Society, 1947).

Deshler, Charles D. “How the Declaration Was Received in the Old Thirteen,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Vol. 85, Issue 506, July 1892, 165-187.

Seth Kaller, Inc records & research

Library of Congress. www.loc.gov/rr/program/journey/declaration.html

Lossing, Benson J. Fieldbook of the Revolution, 1859.

Sotheby’s. “The First Printing of the Declaration of Independence,” May 21, 1993.

Sullivan, Dr. James, ed. The History of New York State (Lewis Historical Publishing, 1927).

Walsh, Michael J. “Contemporary Broadside Editions of the Declaration of Independence.” Harvard Library Bulletin 3, 1949

[1] After Washington’s copy of the Dunlap was read before the American Army in New York on July 9, a mob pulled down the lead statue of George III in Bowling Green. The king and his horse were transported to Connecticut and cast into 42,088 musket balls for the American cause.

|