|

The Authorship of The Night Before Christmas |

Though long acknowledged as the author of A Visit from St. Nicholas (The Night Before Christmas), author Clement C. Moore’s claim to immortality has been questioned by partisans who believe that Henry Livingston, Jr. should be credited for the classic Christmas verse. A careful look at the evidence clearly supports Moore’s authorship, and completely discredits the Livingston camp. Below is Seth Kaller’s response to the controversy, adapted from his article, The Moore Things Change, from the Winter 2004 issue of the New-York Journal of American History.

Note that Seth Kaller formerly owned the only Moore manuscript of A Visit which is now in private hands (three other Moore manuscripts are in museums).

|

|

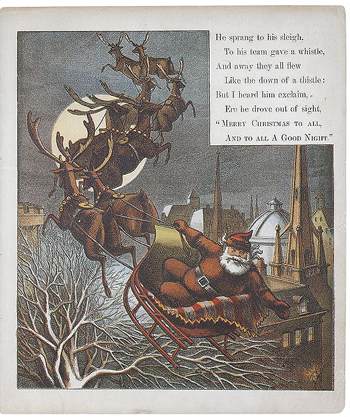

Cover of an edition published in 1888 by McLoughlin Bros.

|

|

|

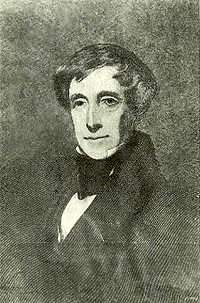

Moore circa 1840 from an engraving of a life

portrait painted for his children.

|

Clement Clarke Moore (1779-1863) was the only child of Benjamin Moore, an Episcopalian minister and rector of Trinity Church in New York City. (The elder Moore would go on to become the Episcopal bishop of New York and president of Columbia College.) His mother, Charity Clarke, was a feisty American patriot. From his mother’s side of the family, Moore inherited the farmland that would, during his lifetime, become New York City’s Chelsea district.

Moore did not follow his father into the ministry. Instead, after his 1798 graduation from Columbia College, he devoted himself to biblical and classical studies, with a focus on ancient languages. Moore’s two-volume Compendious Lexicon of the Hebrew Language, published in 1809, stands as a remarkable achievement and a symbol of his commitment to the beginning student of Hebrew, to whom it is addressed. It was a standard text in the field for many years. In 1818, Moore donated a large tract of land for the re-establishment of the General Theological Seminary, a New York City school for Episcopal clergyman. He served there as a professor of Oriental and Greek literature from 1821 to 1850. During that period, Moore wrote A Visit From St. Nicholas (1822), which he later published under his name in the volume Poems (1844).

According to extant archival evidence, Moore had a vibrant domestic life. He was devoted to his wife, Catherine Elizabeth Taylor, whom he married in 1813. (During their courtship, the smitten scholar composed poems to Catherine, and carved her name on trees.) When she died in 1830, not long after her thirtieth birthday, Moore wrote a devastating poem of bereavement (“To Southey” in Poems). Moore was left with seven children (two had died young) between the ages of three and fifteen. He never remarried, taking on the responsibility of the children’s education and upbringing. One of Moore’s sons, who apparently suffered from a mental disorder, remained at home under his father’s care throughout his life. Moore often wrote poetry for his children and grandchildren.

Clement Clarke Moore was a complex man whose life is best assessed within the context of his own era. Socially conservative, he was an ardent defender of property rights and a strong believer in personal responsibility. While critical of superficial pretense and “fashionable” behavior, he also firmly believed in tolerance and goodwill. The philanthropic Moore gave imaginative service to his community, personally underwriting the debts of Saint Peter’s Church (at an eventual, tremendous loss of $25,000), providing the church with an organ, initiating and teaching for over ten years at a free adult education program, and serving for forty-five years as trustee at Columbia. An erudite professor of theology and “dead” languages, he also loved music, theater and writing poetry for his grandchildren. Though Moore’s 1822 Christmas poem is, in many ways, uniquely reflective of his own period, its appeal has transcended time and place, serving as the basis of our modern-day Christmas rituals. Through Clement Clarke Moore, we continue to celebrate the spirit of love, goodwill, humor and tranquility of the family at home on Christmas Eve.

Let each one enjoy, with content, his own pleasure,

Nor attempt, by himself, other people to measure.

– Clement C. Moore, “The Pig and the Rooster.”

|

|

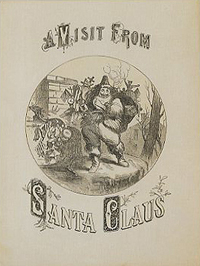

A rare edition, circa 1860, illustrated by Scattergood.

|

In December of 1823, A Visit from St. Nicholas, better known as The Night Before Christmas, was first printed, anonymously, in the Troy Sentinel. By the time Clement Clarke Moore included it in his own book of poems in 1844, the original publisher and at least seven others had already acknowledged his authorship. Four manuscripts penned by Moore, a biblical scholar, philanthropist and father of nine, survive: in The Strong Museum, The Huntington Library, The New-York Historical Society, and one in private hands. When the 83-year-old Moore penned The New-York Historical Society copy, he explained that he had originally composed the verse for his two daughters, using a “portly, rubicund Dutchman” in the neighborhood as his model for St. Nicholas (New-York Historical Society Quarterly Bulletin, January 1919, 111 and 114). Every piece of documentary evidence supports Moore’s authorship. But the facts have not prevented an attempt to turn history upside down.

Decades after Moore’s authorship had been confirmed, a member of the Poughkeepsie-based Livingston family “recalled” that, many years earlier, another family member had claimed that her father, Henry Livingston, had actually written the famous poem. There was no physical evidence. (A single manuscript copy was later said to have been destroyed in a fire.) Still, the clan began a campaign to re-attribute A Visit to the family patriarch. The date attributed to the first reading gradually shifted as details of the claims were discredited. (For instance, an ancestor who supposedly heard the poem read by Henry Livingston at Christmas in 1808, turned out to have died in August of that year.) After successive versions of the story were disproved, the Livingston camp eventually turned to ad hominem attacks. They argued that, unlike their beloved forbear, Moore couldn’t have written such a light-hearted, child-friendly poem, because he was a mean-spirited, curmudgeon, a hater of fun who despised rambunctious children.

|

|

The first page of a signed “fair copy” of Moore’s manuscript.

|

Enter Vassar College Professor Don Foster and his book, Author Unknown: On the Trail of Anonymous (Holt, 2000). Foster admitted that much of the Livingston story had already been proven wrong. Even so, he claimed that linguistic forensics, his own foolproof method of detecting authorship, showed Livingston to be the true author. A reporter for the New York Times picked up Foster’s story, and called me for a reaction. Why me? I believe that A Visit is more than a relic of words on paper. This iconic poem created the modern vision of Santa Claus, a beautiful and captivating story at the center of holiday celebrations welcomed by Americans of every religion. When Moore’s only known privately-held manuscript had come up at auction in 1995, in partnership with my family and another manuscript dealer, I bought it. Having heard the argument denying Moore’s authorship, I replied that there are still people who don’t believe that Neil Armstrong walked on the moon. But, I thought, maybe this time, the accepted wisdom was wrong. So I read the book.

In Author Unknown, Foster repeats the old canard that Moore had been temperamentally incapable of writing the beloved poem. Moreover, he argues, it was stylistically implausible that the stodgy scholar had crafted such sprightly verse. Foster goes beyond prior attacks, claiming that physical evidence proves that Moore had appropriated another man’s work – and that it was not his first such offense. But, Foster’s reasoning is based on a series of flawed arguments, made even less credible by reliance on heavily-manipulated and selectively-used evidence. In the end, St. Nicholas, that “right jolly old elf,” is dragged headfirst down the chimney by a team of runaway fallacies. But with the help of The NYHS and the Museum of the City of New York, we can dust the soot off St. Nick – and Clement C. Moore.

Fallacy #1: Moore was already a plagiarist

Fact: The evidence used to support this assertion is false.

After too many recent reports, we’re ready to believe that plagiarism could be any author’s secret vice. In Author Unknown, Foster claims that in a book about Merino sheep, Moore had included “a handwritten note explaining how he happened to possess such a curious volume: he was himself the anonymous translator! …. he lays claim to an entire book that was the work of another man” (Foster 273-4). Then, voila!, Foster exposes the “fraud”: The last page of the book names the real translator (Foster 273-4).

Had Moore really tried to pirate another man’s work? I asked a research assistant to find the book. Luckily, it was easily accessible, having been given to The New-York Historical Society circa 1814. The text of the incriminating “handwritten note” turned out to be nothing more than a misleading allusion to the inscription “by Clement C Moore A.M.” And what about it being “in his own hand”? It is clearly not in Moore’s handwriting [see Appendix A for this and genuine Moore signatures]. The evidence indicates that the inscription is a clerical error, probably reflecting Moore’s gift of the book. In no way does it show any attempt at plagiarism.

Fallacy #2: Moore was a Grinch

Fact: Every argument marshaled to support this claim is false.

|

|

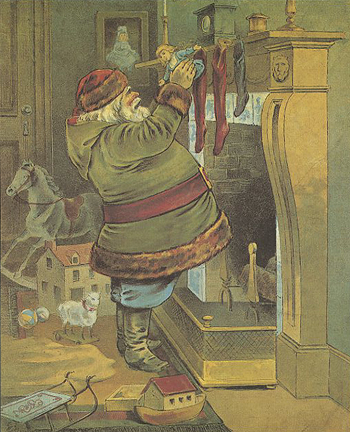

Page from a 1869 edition published by McLoughlin Bros., said to be one of the first American children’s books printed in color.

|

Foster depicts the scholar as a self-righteous, moralizing paragon of rectitude who we can’t wait to deflate. (Foster 227) Moore was incapable of writing this poem, Foster argues, because he was a rich, all-around nasty person, who hated noisy kids, and by the way, his sons were all philanderers. Moore was “a grouchy pedant, a student of ancient Hebrew who never had a day of fun in his life. In fact he was against it” (Foster 227).

Time and again Foster makes his case by misinterpreting, or altering, evidence. In one instance, Foster quotes from one of Moore’s letters to show that “his own mother thought of him as a ‘woman hater,’ a scholar like ‘the long-bearded Jew who […] could love nothing but musty black-leather books’ ” (Foster 247, ellipses Foster’s). But a closer look at the letter reveals the truth – the young professor was poking fun at himself while in the midst of courting his future wife (“my warm-hearted, sweet-tempered girl”).

[W]hat would you do if you could see me through such a magic glass as we read of in the Arabian nights entertainment? The woman hater, the long-bearded jew, who as you all supposed, or pretended to suppose could love nothing by musty black-letter books, is converted into as spruce & gallant a lady’s man as you ever beheld…we ramble about in the country and talk all manner of nonsense; I cut her name upon the trees and try, without success, to make verses….You have long predicted that I should sooner or later be brought to this….” (Moore to his mother, October 16, 1813, NYHS).

How could any objective observer not recognize that the phrase “pretended to suppose” (elided in Foster’s quote) is a clue that Moore is kidding?

But what about the child-hating, noise-obsessed Moore? A passage from an unpublished 1849 verse, written by the poet for his granddaughter, puts the lie to that characterization: “The house is all too dull and quiet;/ I long to hear you romp and riot/ When e’er you’re full of harmless fun,/I dearly love to see you run” (Misc. Moore, C.C. Coll. Museum of the City of New York).

Fallacy #3: Moore was a Scrooge

Fact: Moore celebrated Christmas and also wrote what is probably the first “letter” from Santa Claus.

Moore, Foster claims, disapproved of verse that was not spiritually useful and abhorred the veneration of saints – including St. Nicholas. “From Moore’s point of view,” states Foster, “Christmas was no time to be jolly, but a season for worship, for repentance from sin…. When the evidence is laid out on the table, one cannot help but wonder how “A Visit from St. Nicholas” ever came to be associated with an old curmudgeon like Clement Clarke Moore in the first place” (Foster 245; 266).

So was Moore indeed morally and constitutionally incapable of writing A Visit? Absolutely not. Proof positive is in the Museum of the City of New York, where we discovered a previously unknown Santa poem. It is written, without a doubt, in Moore’s handwriting. Based on content and the addressee, one of Moore’s daughters who was just learning to read, it probably predates A Visit by one year. In the form of a letter in verse (perhaps the first letter written by Santa Claus), it provides another major link in the story of the invention of the modern Santa.

Fallacy #4: Stylistic evidence proves that Henry Livingston wrote the poem

Fact: Even a scientist can be wrong, if he relies on tainted evidence. “Linguistic forensics,” if fairly employed, actually proves that Moore is the author.

Foster and the Livingston camp claim that a linguistic analysis of A Visit supports Livingston’s claim of authorship and opposes Moore’s. Are they right?

|

|

“He spoke not a word,

but went straight to his work,

And filled all the stockings:

Then turned with a jerk.”

|

As Dr. Joe Nickell, author of Pen, Ink and Evidence, points out in his thorough analysis of Foster’s work, “[i]t is easy to fall into the trap of starting with the desired answer and working backward to the evidence, picking and choosing that which best fits” (Nickell, Manuscripts, Winter 2003, 10). That’s just what Foster does, using linguistic analysis selectively, and disregarding all evidence in favor of Moore’s authorship. Lighthearted, spontaneous-sounding mixed iambs and anapests, exclamation marks, the “rare” use of “all” as an adverb, syncopation, familial affection – the “evidence” for Livingston can also be seen in many lines written by Moore. And let’s not forget the language. When Foster discusses the origin of certain words or phrases from the poem (“all snug,” for example), he goes to tortuous lengths to create an association with Livingston, only to ignore much more direct connections to Moore. In any case, the circumstantial evidence that Foster cites to support his claim, even if it were true, would still prove nothing. Livingston might have been likelier to employ a particular word or style of punctuation, but this does not mean that Moore never did so. As already shown, there is both documentary and historical evidence supporting Moore; the same cannot be said for Livingston.

A broader analysis, however, yields more conclusive results. Foster and the Livingston family now claim that the poem was written by Henry Livingston circa 1808. But as shown in Stephen Nissenbaum’s 1997 book, The Battle For Christmas, the poem clearly reflects the later influence of Washington Irving, The New-York Historical Society and the Knickerbocker movement, once again pinning authorship to Moore. Contextual sources date the poem to 1822, consistent with all the other evidence that Moore penned the classic verse.

In the end, Foster bases a great deal of his claim on his high opinion of Henry Livingston, “an artist, journalist and poet… a free spirit and all-round merry old soul if ever there was one” (Foster 227). In today’s world, many would feel comfortable believing that we owe our much-loved “jolly old elf” of Christmas to a free spirit, not an earthbound pedant. But Moore’s creation is all the more moving, having arisen from the private heart and imagination of a publicly serious scholar.

Let’s give the final word to Mr. Moore, with an excerpt from a manuscript poem in the collection of The New-York Historical Society (Misc. MSS Moore C.C.). Likely written in 1813, on the occasion of his marriage to his beloved Catherine, Biography of the Heart of Clement C. Moore offers the poet’s clear-eyed assessment of his own character.

He shone not with the fire-fly’s light,

Which shows itself in flashes bright,

But with the glow-worm’s steady ray

The constant lustre of the day.

That steady ray still lights up the faces of children every year on Christmas Eve.

The Authorship of The Night Before Christmas cont'd

|